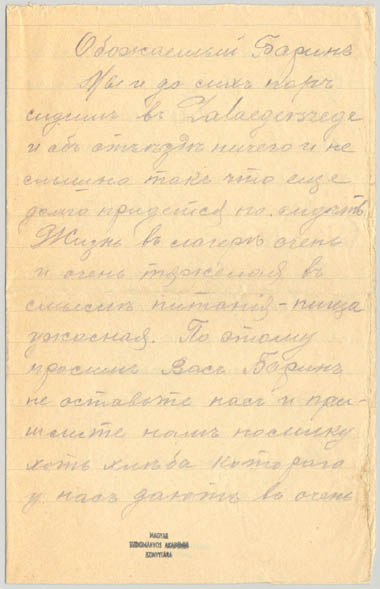

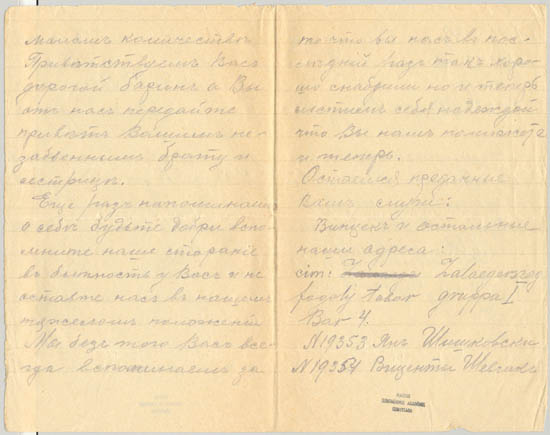

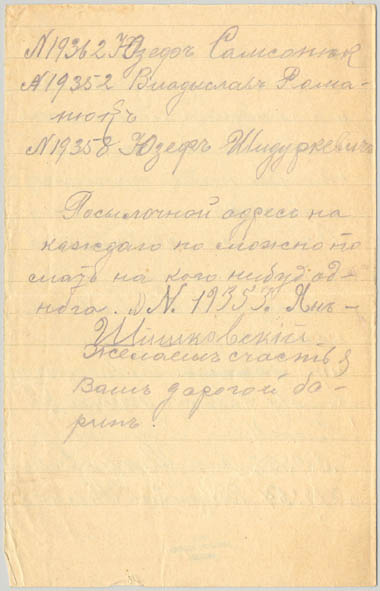

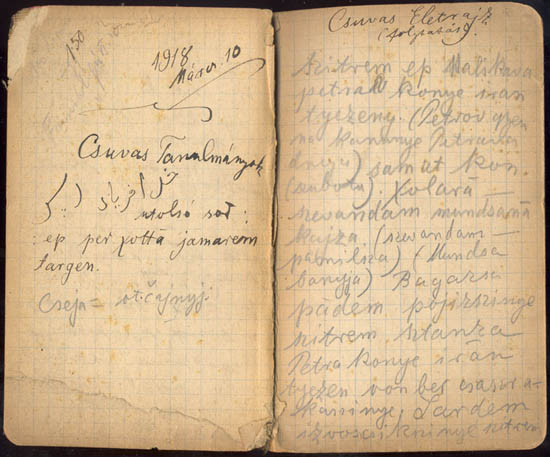

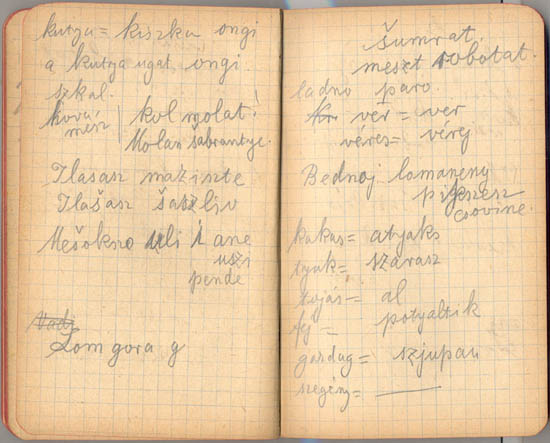

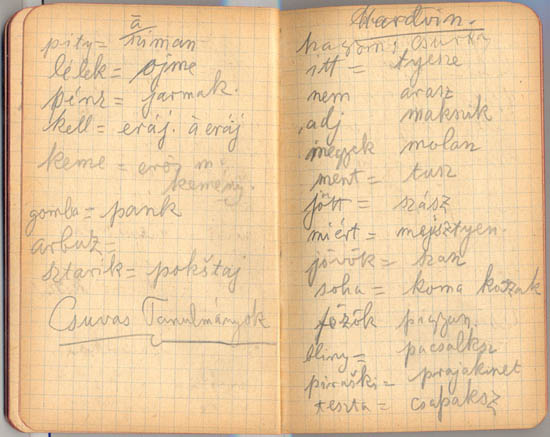

Ivan Aleekseevich Vladimirov, painter of the pictures in the previous post: Hungarian soldier, 1915

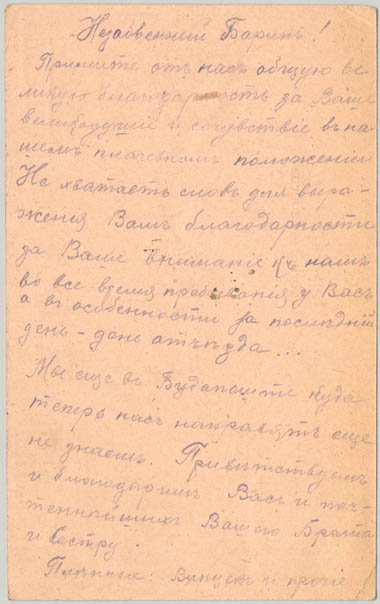

Ivan Aleekseevich Vladimirov, painter of the pictures in the previous post: Hungarian soldier, 1915 The realistic images of the siege of the Winter Palace reminded me that it’s time to repay an old debt of mine. In the eighties I got acquainted with Gergely Bors, who was then already past ninety. In the Transylvanian Székely village of Csíkmenaság, the eastern curve of the Carpathian Mountains, high in the head of the valley, where I spent a day in the captivity of the church hill flooded by the mountain rains. A village about which most Hungarians only know from the folk song Fly, bird, fly, to Menaság fly

The realistic images of the siege of the Winter Palace reminded me that it’s time to repay an old debt of mine. In the eighties I got acquainted with Gergely Bors, who was then already past ninety. In the Transylvanian Székely village of Csíkmenaság, the eastern curve of the Carpathian Mountains, high in the head of the valley, where I spent a day in the captivity of the church hill flooded by the mountain rains. A village about which most Hungarians only know from the folk song Fly, bird, fly, to Menaság flyMuzsikás and Márta Sebestyén: Fly, bird, fly

| Repülj, madár, repülj, Menaságra repülj édes galambomnak gyenge vállára ülj vidd el, madár, vidd el, levelemet vidd el apámnak s anyámnak, jegybéli mátkámnak ha kérdi, hogy vagyok, mondjad, hogy rab vagyok szerelem tömlöcben térdig vasban vagyok rab vagy, rózsám, rab vagy, én meg beteg vagyok mikor eljössz hozzám, akkor meggyógyulok | Fly, bird, fly, to Menaság fly, sit on the delicate shoulders of my sweet dove take my letter, bird, take it to my father, mother and to my fiancé if she asks where I am, tell her I’m a prisoner in the prison of love, in chains till my knees you’re a prisoner, my rose, however, I’m sick only when you’ll come to me, I will heal. |

(Before I included the original Hungarian text with English translation, Araz fell so much in love

with the song that he sought for a video with translation– and with the beautiful photos

of the Transylvanian Kolozsvár –, and he translated it in Azeri for Shahla:

Uç, ey quş, havalan, Menaşaqa uç, qon yarımın çiyninə.

Götür, ay guş, məktubumu, yetir ata-anama, həm deyiklim gəlinə…

Halımı soruşsalar, de ki, dustağam sevgi zindanında, zənciri dizə qədər.

Zindandasan, gülüm, mən isə xəstə, bircə sənin gəlməyin dərdimə dərman edər…)

I was surveying the medieval churches of the valley of Csík, as I will once recount it, and I was trying to collect the ephemeral written and oral memory. “Go to Uncle Gergely”, they told me. How embarrassing it was to give over two hundred and fifty grams of coffee, a trifle for me, a treasure in Ceaușescu’s Romania. Books were laying the table, the stories flowed from Uncle Gergely, and a refreshing air bubble covered that afternoon in that horrible, suffocating world.

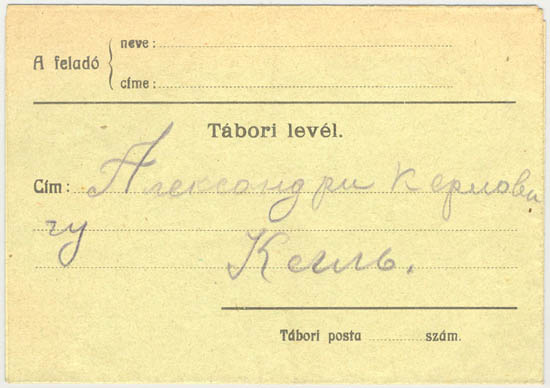

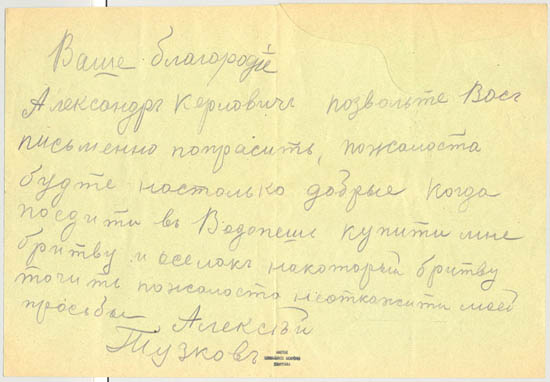

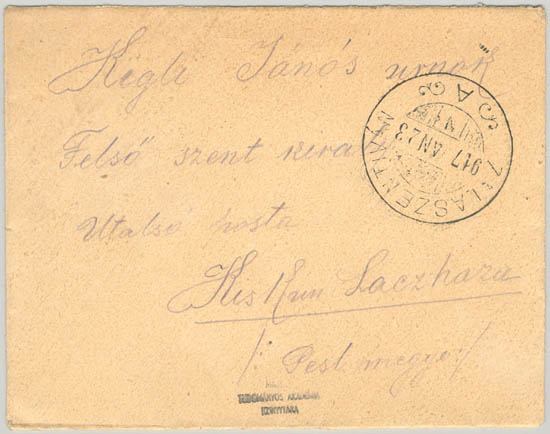

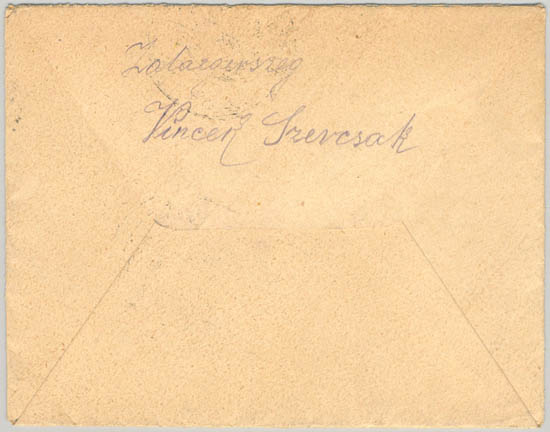

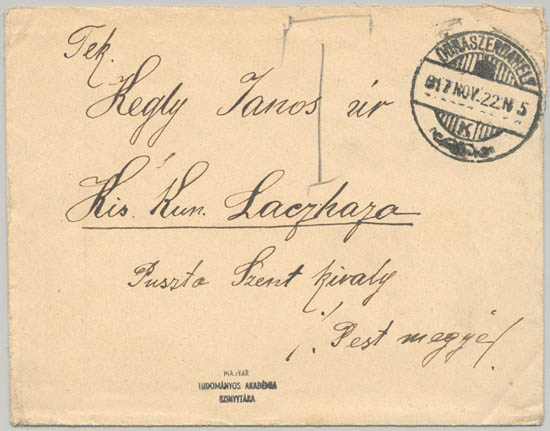

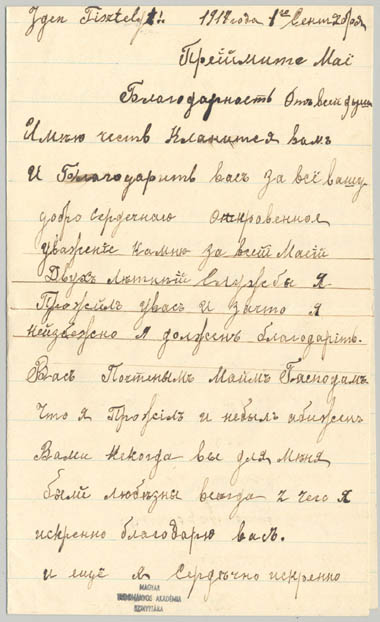

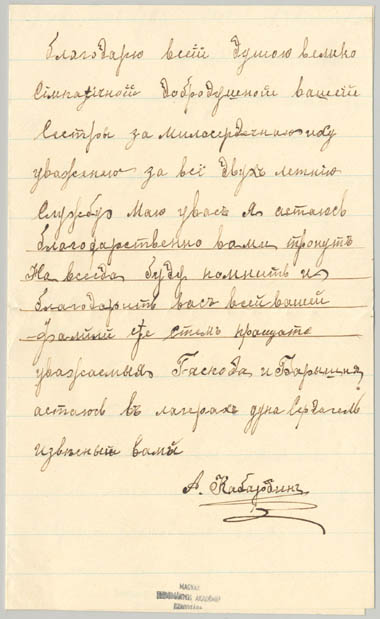

Veteran’s document from Csíkmenaság. From the family photo collection campaign of Menaság

Veteran’s document from Csíkmenaság. From the family photo collection campaign of MenaságI recounted that afternoon a good many times. “Come on, the old man drew the long-bow”, said Sergei in disbelief in the Fatâl restaurant. Nonsense, Lenin’s body guard? “Well, he took out a photo and showed that this is Lenin, this is Stalin, and lo, this is me.” “You should write this for a Russian journal, we would immediately publish it.” I should have, ever since, more than once.

Still, I give the word to a listener much more authentic than me. The touching little book Csíki kaláka (Mutual help in Csík valley) by Farkas-Zoltán Hajdú, living since 1987 in Heidelberg, and intensively engaged in the research of both Székelys and Saxons, was bought by me in 1993 in the Hungarian bookshop of Csíkszereda / Miercurea Ciuc, from hundreds of other beautiful books printed on bad paper with bad letters, which have since disappeared without a trace from the Hungarian book publishing.

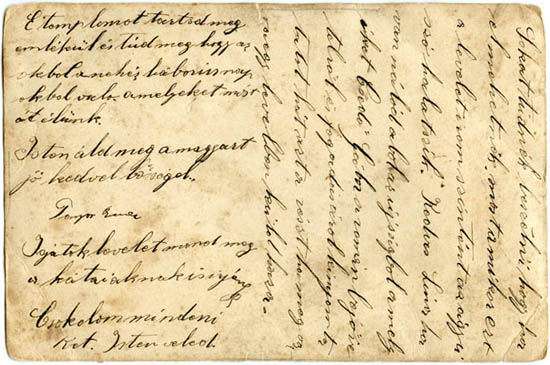

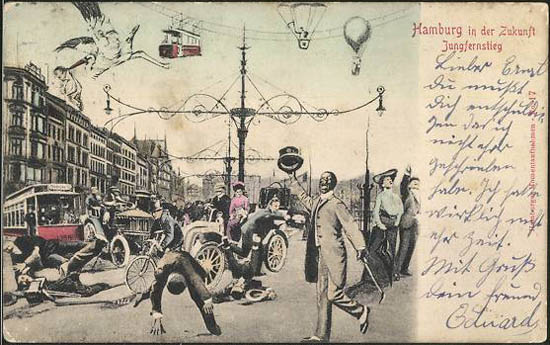

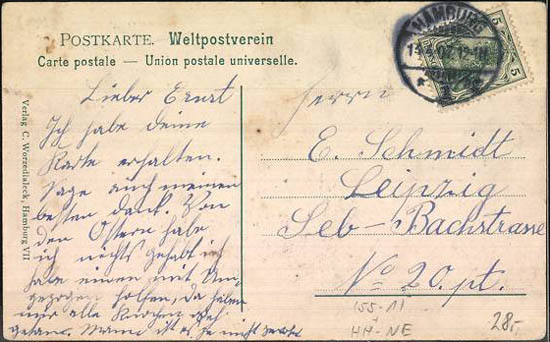

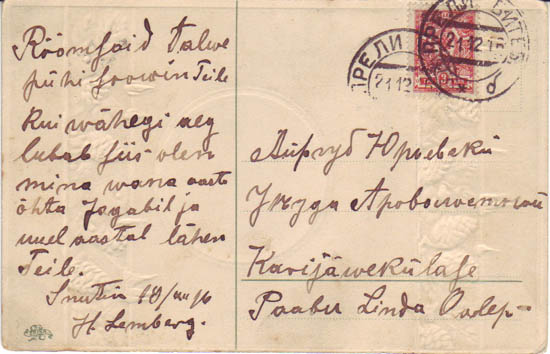

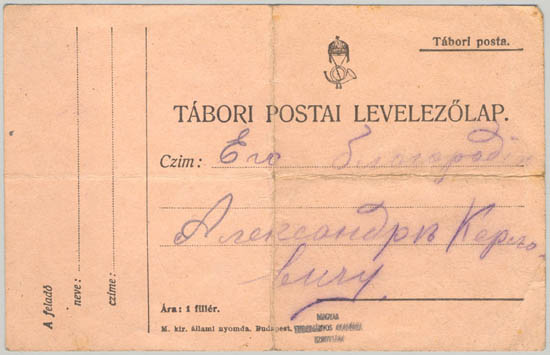

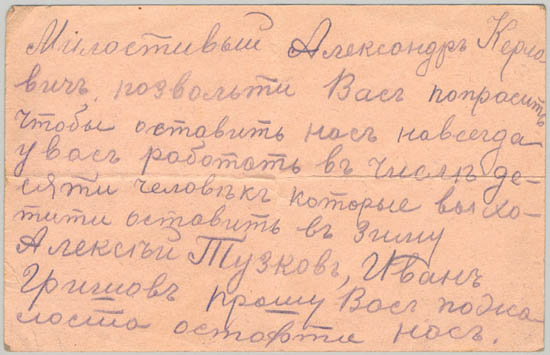

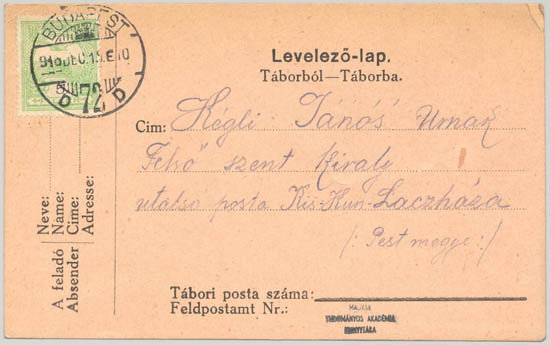

WWI postcard sent from Csíkmenaság to the front. “Keep this church in your memory, and know that it was built in days of heavy war, just like those we live now.”

WWI postcard sent from Csíkmenaság to the front. “Keep this church in your memory, and know that it was built in days of heavy war, just like those we live now.”“…This was my first encounter with Menaság. At that time this village was like all the others visited by us in that summer. I have not even heard of it before. It fell away from the main road, and did not seem superior to the other villages in Csík. For a long time I did not go back there, and did not think to ever return.

However, within two or three years I had a the opportunity for a new encounter. I was taken by car not exactly to Menaság, but to its neighborhood Csíkszentgyörgy, by my wife still breast-feeding our daughter, to meet Gergely Bors. The famous Gergely Bors, Lenin’s personal bodyguard.

It was spring, my wife was in a hurry, so I could go to the old man above ninety only between two breastfeedings. We were left alone. He already guessed why I came to see him, for many had asked him before about his Russian memories, some officially, and some just for the sake of the tales. At some time he had also received a pension from the Soviet embassy, but now only the journal Aurora was brought to him by the lame postman, with smaller or longer interruptions. In his lean, dry, mustacheless figure there was something non-peasant. Yes, he had the clear openness of widely traveled people. His hair was brushed aside, and he received me in a pajama jacket. Books were laying on the kitchen table, some of them densely underlined by pencil. His eyes sparkled from his face full of wrinkles, and already his mimicry revealed his being a great story-teller. His story is very similar to all the soldier’s stories heard before or later, which old people recount with so much predilection in the pubs, while nursing a monopol or a caraway seed. Each family had its men who had been to war, and their stories were proudly revived by their descendants, through several generations. These stories were similar to the dog’s skin charters which guaranteed a family’s reputation for many decades.

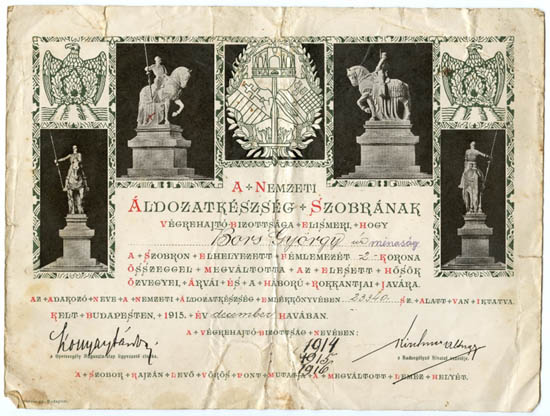

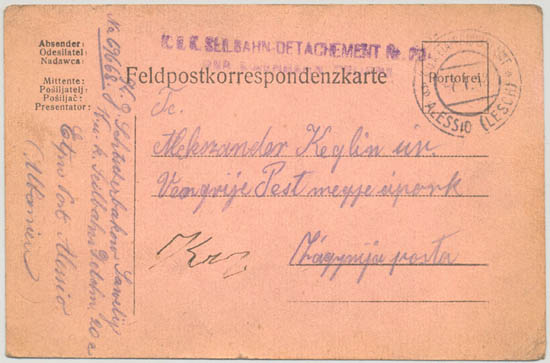

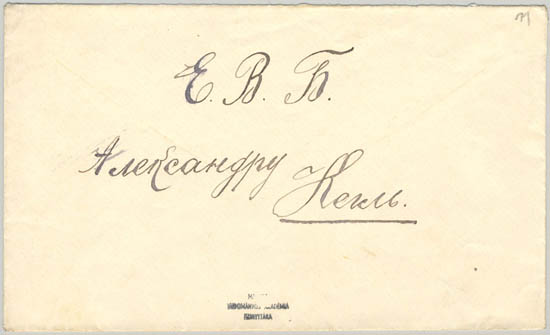

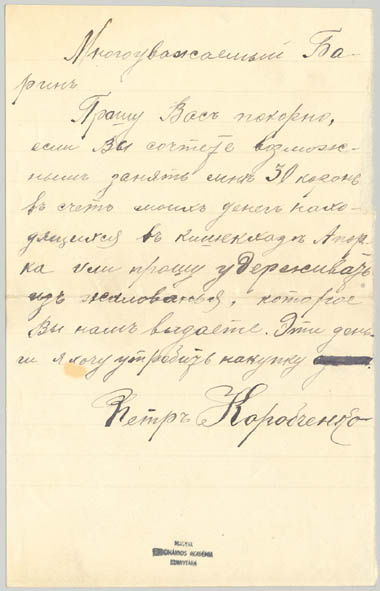

Official document on György Bors’ (Csíkmenaság) contribution to the Statue of National Generosity, 1915

Official document on György Bors’ (Csíkmenaság) contribution to the Statue of National Generosity, 1915The experiences of military and prison remain always vivid in the memory of local people. Their main figure is not the valiantly fighting soldier, but much rather the clever lad who, escaping from captivity, sets on the road home with a single shovel, and every time he is seen with suspect, he starts to adjust the roadside stones in the most natural way. The road is much longer in this way, but it surely leads you home. A better story matures into an anecdote, and it will be recounted not only by its “owner”, but by everyone who heard it. Later I became acquainted with old men who for some reason quarreled in the Russian captivity, and since then they have remained mortal enemies. Then and there, the stake of the game was life or death, and the memories are too fresh for a whole life to prevent forgiving treason and disloyalty.

Very interesting is the general opinion shared about foreign soldiers. In war stories, the German soldier is always polite, but, although distributes chocolate to children, very strange; the Russian, although he takes away everything, and an ignorant, wild and very ragged fellow, is nevertheless kind-hearted and pious. Does the fact that we are also from the East, made more sympathetic the soldiers coming from Asia? Maybe our subconscious self registered the common roots?

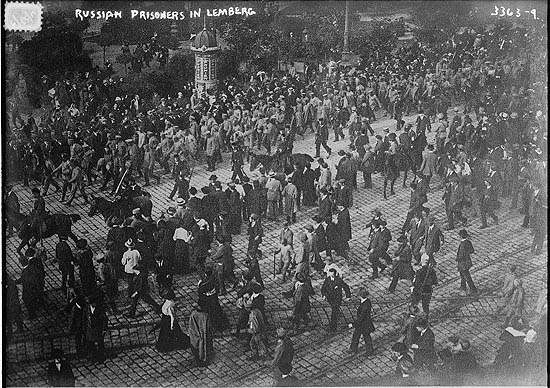

Well, Gergely Bors as a young man, was enrolled in Franz Joseph’s army as it is the way of things, and in one of the first battles he was captured by the Russians, as it is the way of things, in a huge fog, in the middle of a thick forest. He traveled over half Russia as a prisoner of war, and finally put up at a rich peasant in some godforsaken village, to cultivate the land. They really liked “Gligor”, who loved the earth just as much as they, and could work the wood as nobody else. Then one day it was his host’s turn to go to the army. There was much weeping in the family, but only as long as the old people did not find a better solution. Coup de théâtre: they send Gligor instead of the host, because in this way, closer to his homeland, perhaps he would manage to escape.

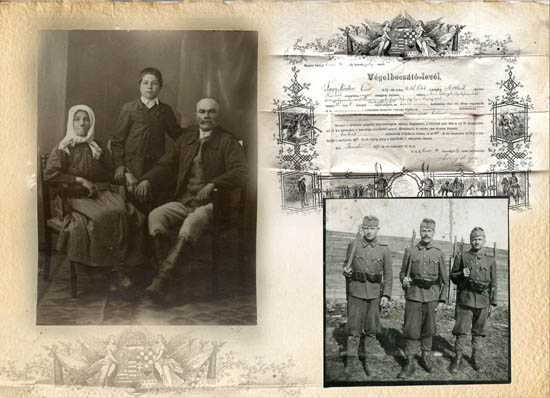

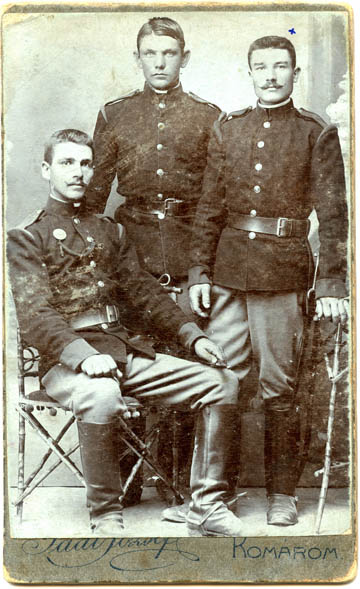

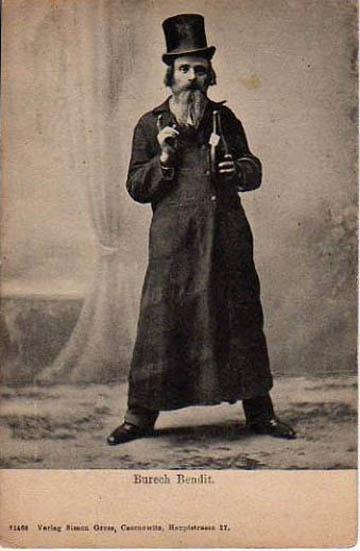

Gunner György Bors from Csíkmenaság (whether a relative to Gergely?). WWI photo from a Komárom studio

Gunner György Bors from Csíkmenaság (whether a relative to Gergely?). WWI photo from a Komárom studioThe replacement was succesfully done – with the help of some liters of vodka –, and Gligor, who already had a good command of Russian, soon finds himself to be at a big city station as a Russian infantry. Another coup de théâtre: someone hits him in the back: – Mr. Bors, what are you doing here? – The person asking it is the wood merchant, who, before the war, made a lot of good board deals with Gergely’s father. After the first fright, the heaven-sent acquaintance offers him a good business: to enter a new service. The nature of it is still a secret, but success is guarantee. For now, a very important person has to be waited for at the station, and for this, they need just a handsome sturdy Székely lad who is not afraid of his own shadow, and has his mind in place. The identity of the person is still a secret for now, but Gergely Bors is not too much interested in it, the point is that he receives a modern automatic pistol, and plenty of food. The stranger waited for in secret arrives in secret, at night. A stocky little man in big black coat, another Jewish-looking one.

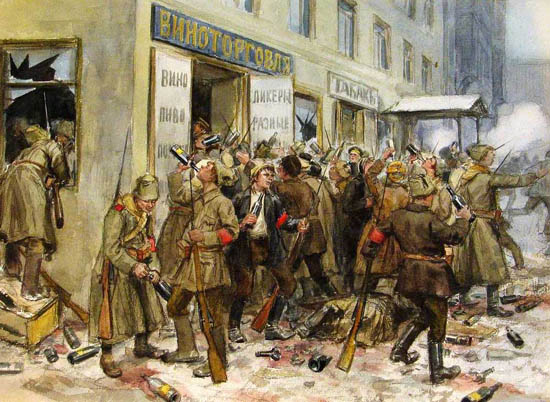

The events accelerate, and Gergely Bors is also on Lenin’s side at the siege of the Winter Palace. His heart is in the place, and he is well kept. His companions are also strangers, desperate fellows.

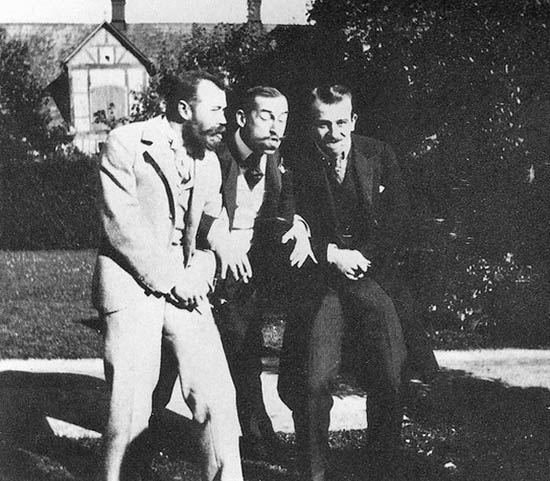

(I’m shaking my head in disbelief, he soon discovers it. He takes out his photos from the drawer: – Well, young man, look here: this is here Lenin, Krupskaya on his side, next to them, me, with bandaged head, and on my left, Stalin – let plague eat him – together with his son…)

From the siege of the Winter Palace he only remembers that it was wickedly cold, and the Tsarist cadets there inside were ordered to destroy the Czar’s vodka stocks. They began to scrupulously pour the spirit into the drains, which was soon noticed by someone outside there, noting that in the canals there is flowing vodka instead of sewage… The consequences are obvious… it was very cold, and with a good amount of vodka it was easier to bring the blood-red flag of the revolution to victory. At the end of the fight only Lenin and a few others from his immediate surroundings were sober.

Gergely Bors remained in Lenin’s personal bodyguard unit, accompanying him as a shadow everywhere, to public rallies and meetings. The most unpleasant memory is Stalin, that is, Dzhugashvili, as they called him at that time. A big bully and an arrogant man. Together with his son they rape women in the street in broad daylight, and he hates foreigners. When drunk, he repeatedly attempted to crush Lenin’s life, then he’s a real beast. Lenin, he is very good, a good old man. He distributes the food parcels sent to him even during the greatest famine, and he’s already ill, very ill. Gergely Bors at the first chance skips off, and soon he is in the territory of “Great Romania”, in the unpleasant, awkward brave new world. At home, as if nothing happened, the village readmits him smoothly, and he also turns back without a word into a Székely farmer.

Forty-four. Russian soldiers, who do not understand his memories any more. Later, official interviews. A short biography and pictures in a book on the heroic participation of Romanians in the “Great Revolution”. Pension, and then only Aurora. And with this completes Gergely Bors’ career on earth.”

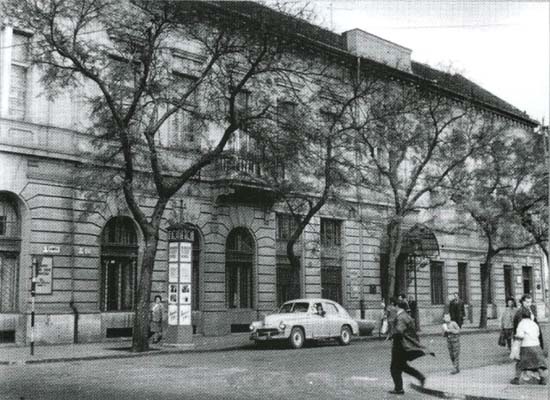

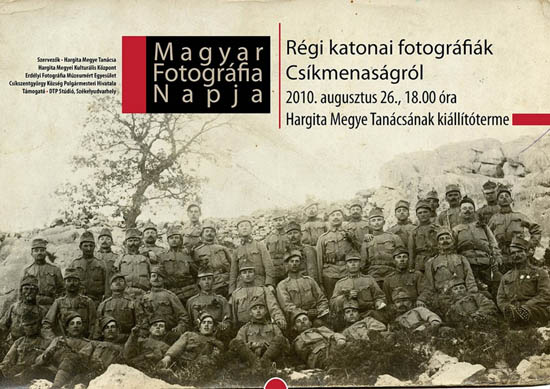

Exhibition: Old military photographs from Csíkmenaság. From the report of the Photo Witness blog

Exhibition: Old military photographs from Csíkmenaság. From the report of the Photo Witness blog

Quand j’étais petite fille, elle était une très vieille dame aux cheveux toujours noirs et au visage poudré de blanc. Je l’écoutais parler mais je ne comprenais pas vraiment ce qu’elle disait — peut-être parlait-elle une langue qui m’était étrangère. A vrai dire, elle m’effrayait beaucoup et je n’aurais pas voulu qu’on me laissât seule avec elle.

Quand j’étais petite fille, elle était une très vieille dame aux cheveux toujours noirs et au visage poudré de blanc. Je l’écoutais parler mais je ne comprenais pas vraiment ce qu’elle disait — peut-être parlait-elle une langue qui m’était étrangère. A vrai dire, elle m’effrayait beaucoup et je n’aurais pas voulu qu’on me laissât seule avec elle. When I was a little girl, she was a very old lady with still black hair and white-powdered face. However I listened to her, I did not really understand what she was telling – perhaps she spoke a language foreign to me. Actually, she scared me a lot, and I would have not wanted to be left alone with her.

When I was a little girl, she was a very old lady with still black hair and white-powdered face. However I listened to her, I did not really understand what she was telling – perhaps she spoke a language foreign to me. Actually, she scared me a lot, and I would have not wanted to be left alone with her.

The Italian literary and cultural journal

The Italian literary and cultural journal

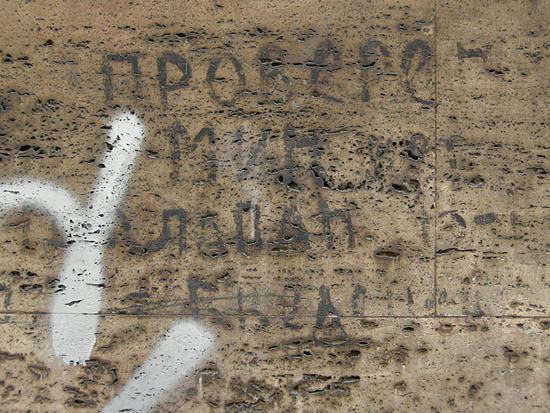

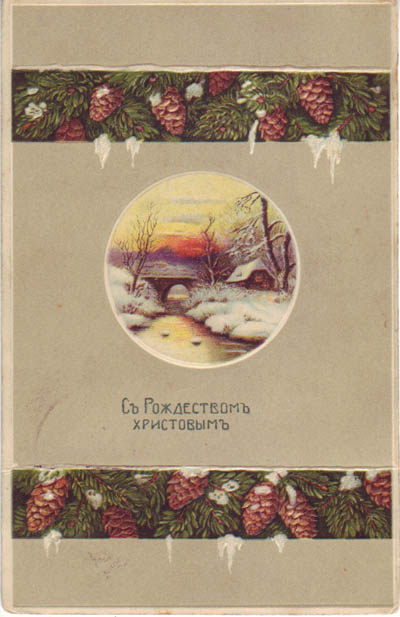

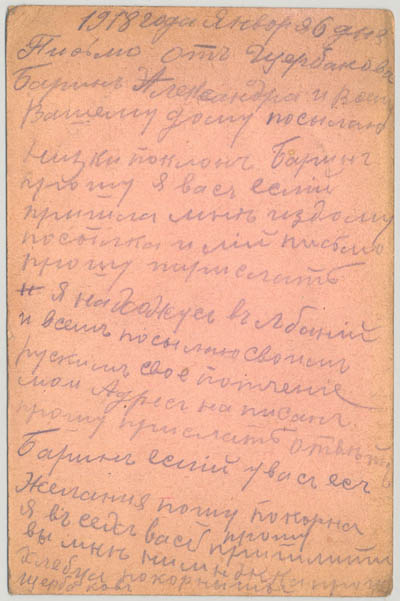

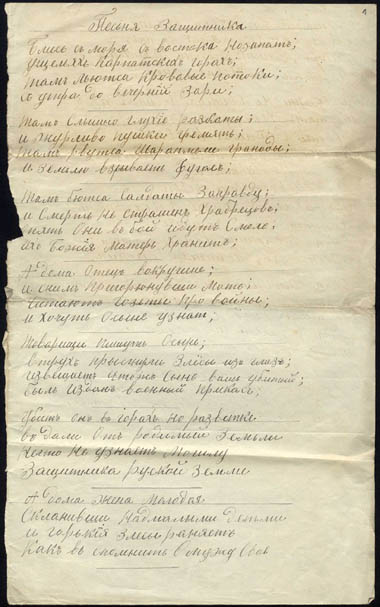

Девяносто пять лет назад, 6 января 1918 года, в праздник Рождества Христова,

Девяносто пять лет назад, 6 января 1918 года, в праздник Рождества Христова,