Moving south by train from Prague via Salzburg, past Austrian Alps that shine like gods in the afternoon sun, then in darkness through solid rock under mountain borders, the fluorescent tube lighting of the long train tunnels sweeping the interior of my compartment like a photocopier, I at long last descended to the port city of Trieste, on a seaside strip of Italian land, cupped within Slovenian mountains.

Moving south by train from Prague via Salzburg, past Austrian Alps that shine like gods in the afternoon sun, then in darkness through solid rock under mountain borders, the fluorescent tube lighting of the long train tunnels sweeping the interior of my compartment like a photocopier, I at long last descended to the port city of Trieste, on a seaside strip of Italian land, cupped within Slovenian mountains.

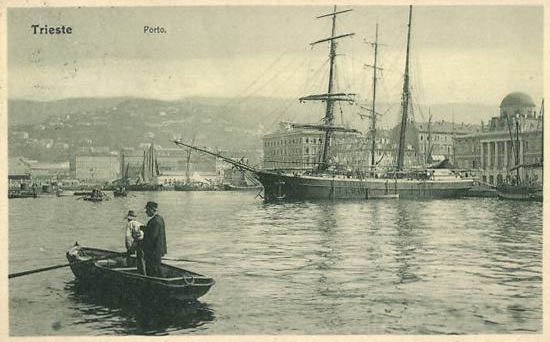

The story of Trieste, founded by Illyrians, ruled by Rome, then Byzantium, then enduring conflict with the Most Serene Venetian Republic and then, unsteadily, coming under the Hapsburgs, Napoleon, or intermittently finding purchase as a free city state, finally gives us today an Italian city braided also with thick Slavic and Germanic strands. James Joyce made it his home for many years, and his friendship with Italo Svevo helped make the latter a treasured voice in Italian literature. Each is memorialized in his own city landmark.

But our subject here is another Triestine landmark, an understated one of almost vanishing subtlety. It is no higher than the pavement on which it rests, and few that pass pay it any heed. Most people that I observed, Triestines and travellers alike, tread callously upon it as they go about their activities. I came across it simply as an accident of my haphazard wanderings and, as such things often do, it struck a resonant chord. I am speaking of the Trieste Meridian.

The word “meridian” is from the Latin words “meridianum” and, as such, it marks the line over which the sun is always at its daily zenith the year round for a given location. This is the noon or “midday” alluded to in the Latin above; that is, the middle of the day.

If I define a meridian in geodetic terms, saying that it is any section of a great circle on the terrestrial sphere that has both planetary poles as endpoints, we can understand, with perhaps a bit of effort, what is meant. But there is the lingering feeling that language this precise, ironically, starts to sound meaningless. In simpler terms, we may say that any straight north-south line on the earth’s surface is a meridian. And that there are infinitely many of them. In choosing this meridian, and making it manifest on the pavement, the Triestines are saying that it is somehow special.

London and Paris

It is special, but not unique. There is, for example, the consensus Prime Meridian that passes through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, a London borough, and, at 0°, is the meridian from which all other conventionally understood longitudes are measured. Before this was accepted, however, the meridian at Paris was considered by many a competitor for the honor. On many maps of French origin, in fact, you can still see both meridians are referenced in the margins.

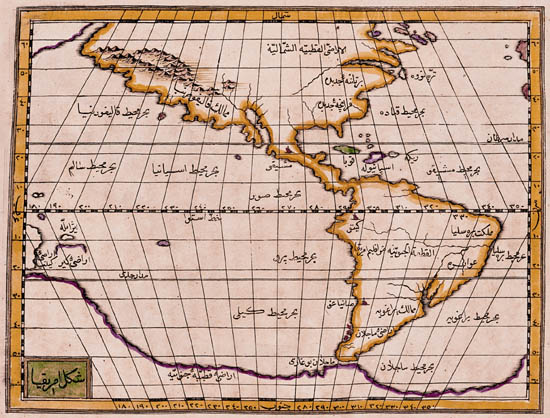

During the International Meridian Conference in 1884, held in Washington, U.S.A., a good many alternative meridians were discussed, some on the basis of political neutrality and others for reasons of tradition. One proposal supported placing the Prime Meridian at El Hierro (Ferro), in the Canary Islands, a practice established in 1634 by the French, but based on a tradition dating from Ptolemy, who considered the “zero point” to be the westernmost point in the known world (or, in 1634, the “old world”). But as Greenwich had become the de facto standard gradually over time, it was generally felt, I suspect, that it would be best to leave it be. The French had to leave the conference dissatisfied.

But there is (was!) also a system of local prime meridians, intended to serve the limited chonometric needs of the people in their surroundings. Their august presences have dissipated over time from having been essential local features and exemplars of the timekeepers’ art, until now they are little more than atrophied historical appendages, modest curiosities at best. My favorite kind, as a matter of fact: the withering obscurity. For the curious, Wikipedia tells more about the Prime Meridian, and even offers a list of other prime meridians that are of merely local importance.

Here I will share what I've managed to find, in summary form, about the two prime meridians I've happened to trip over and, at the end, I wonder aloud how many more exist.

Trieste

The Trieste Meridian (13°46´11˝ E) is marked by three inscriptions on a narrow strip of pale stone cutting a swathe through the cement paving slabs of the Piazza della Borsa. The first simply identifies it as “Meridiano di Trieste” and the next gives instructions for how to make oneself the gnomon of a sundial, and read the time of day with your own shadow. The final inscription memorializes the efforts of its designer, the Friulian scientist Antonio Sebastianutti, who accomplished the work in 1820. The meridian strip’s northern end terminates at the base of the outer wall of the Camera di Commercio (Chamber of Commerce).

The inscription also alludes to a “camera obscura” as part of the ensemble, but for that, you must enter the abutting building. The meridian as demarcated outside continues into the interior of the building, where an indiscernible opening high in the wall allows a shaft of sunlight to penetrate and project the solar disc onto a series of markings on the floor of the entry hall, which discloses the precise time of day. When it was devised, the purpose of this elaborate, and strikingly elegant, system was to provide a precise method for ships long out at sea, upon returning to port, to calibrate their chronometers, which in those days were vital to navigation.

Prague

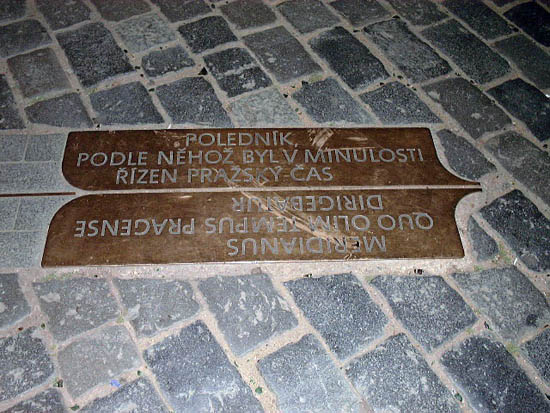

The start of my journey to Trieste began in Prague, a city that, interestingly, also boasts its own prime meridian. The Prague Meridian (14°25´17˝ E) passes through Staroměstské náměstí (Old Town Square), and, if you can manage to elbow your way through the crowds of tourists, you will see that it is marked by a brass rule and plaque embedded among the cobbles, pointing obliquely in the general direction of the memorial to Jan Hus. But this ensconcement is merely a historical ghost, marking a trace of a shadow of a hint of something that no longer exists.

Until the spread of railroads and the subsequent introduction of Standard Time, the city of Prague, like probably every other city and town in the industrialized world, had its own local time. The local time for each place varied, for the simple and logical fact that the sun was at zenith at a different time in each location, depending on its longitude. Prague by tradition and convention established that midday was the precise time that the Mariánský sloup (Marian Column), a 16-meter-high devotional column topped with a shining effigy of the Virgin, cast its shadow along a true north-south line onto the pavement. The line of that fleeting shadow is the Prague Meridian.

A separate, but connected, inscription among the paving stones of Old Town Square marks the former site of the Marian Column. The column was pulled down shortly after Czechoslovak independence in 1918 by a certain group of scoundrels, still smarting from the Bohemian defeat at the Battle of White Mountain 300 years before, claiming that the column still represented Hapsburg repression.

The column, although erected in the period of the many so-called “plague columns” that appeared throughout central Europe during the era, does not strictly fit that archetype. It was begun in 1650 “…in thanksgiving to the Virgin Mary Immaculate for helping in the fight with the Swedes,” according to Wikipedia. Its aim seems at least partly political: Golo Mann, writing in “Das Zeithalter des Dreißigjährigen Krieges,” from the Propyläen-Weltgeschichte, reports the curious fact that, officially, the Virgin Mary had been appointed the commander-in-chief of the Austrian army during their wars with the Protestants. The Battle of White Mountain against the Hussites was their first victory after having done so.

To this day there are unfulfilled initiatives to re-erect the structure, and the City of Prague has taken it under advisement. But still no decision on the matter has been handed down. It remains controversial. At issue are, not only the cost of the reconstruction, but also concerns by architectural experts that the existing documentation of the original column is insufficient to create a historically correct structure. The inscription marking the site of Marian Column reads “Here stood and will stand again the Marian Column,” but the words “and will stand again” have apparently been intentionally chipped away by person or persons unknown.

And now, You

After stumbling upon these two lesser meridians, that their local communities evidently find of enough significance to devote treasure and effort to their commemoration, I am left to wonder, what other minor prime meridians are out there that few but local citizens know about? We have Wikipedia’s list (linked above) to tell us of some, but, for the sake of the game, I am going to presume that there are many more.

So, please, dear reader, I ask you, if you should know of one, maybe in your home city, or that you’ve come across in your own travels, will you please leave a comment to this post with some small bit of information about it? And if you should have a picture of it, could you a share a copy with us? I believe it could form a very interesting collection of crowd-sourced knowledge that anyone interested in such things might benefit from.

In Closing

We all know that the features that appear on a good map correspond to features that appear somewhere on the Earth. The model for understanding mapped space is abstracted and distorted, projected onto a two-dimensional space so that it can be printed on flat paper. The map is peppered with dots representing population centers, squiggled with borders, and ruled with lines allowing coordinates to be plotted for quick reference. But what happens when we turn the idea around and begin to place markers on the earth that correspond to the way space is organized on maps? Our geodetic techniques give us crystalline constructs of pure imagination, an idealized conception that helps clarify relationships, sometimes at the expense of precise detail. In marking these imaginary lines upon the face of the earth, the brain’s inner theatre exercises its will in form and matter. The pure constructs of mental effort protrude into the very space they are attempting to describe, and therefore change it. So now there is something new on the earth, a monument to a meridian line. In turn, it now it must appear on some map, lest the map become outdated and false.

But this is a tangled hierarchy that I will leave to Borges and the philosophers.