![]()

| The tours of río Wang grew out of this blog at the request of our readers. For the eighth consecutive year, we have been organizing tours to regions that we know well and love, and which are not to be found in the repertoire of tourist offices; or even if they occasionally are, they do not delve so deeply into the history and everyday life of these places, the tissue of little streets, interior courtyards, cafés and pubs frequented by the locals: to the Mediterranean, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Iran, the Far East.

Our journeys are no package tours, but rather the excursions of friends. Almost always there is someone who admits to never having wanted to take part in a package tour, but could not resist the call of the blog. And in the end he/she recounts with relief that it has absolutely been no package tour. We consider it a really great compliment.

For fresh news, sign up for our mailing list at wang@studiolum.com!

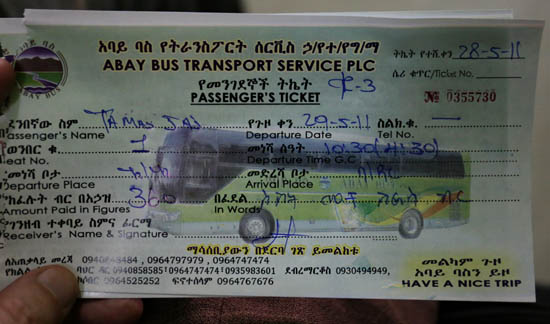

About myself: Dr. Tamás Sajó, art historian, translator, blogger. I live in Berlin, from which I organize my tours. I speak and translate in fifteen languages. I have worked at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Central European University in Budapest. In fact, the tours I organize are also peripatetic university lectures. | |

![]() Our 2020 tour calendar

Our 2020 tour calendar has taken shape through the conversations during the previous trips and blog meetings, and all of the subsequent correspondence about them. The participants have told us where they would prefer to go, and their votes on the first proposal, which was sent out in a circular letter, has decided which tours to actually organize. Meanwhile, for some trips the maximum number of participants – 9 or 18 persons, the capacity of a small bus – has been also reached. So if, in the future, you want to take part in the shaping of the tour calendar, and want to be sure you do not miss out on the most popular tours, sign up for the mailing list at

wang@studiolum.com.

In previous years, there were many tours we organized only once or twice, while the interest in them was increasing. This is why we announce many familiar trips again this year. Once again we visit

Rome, Sicily, Andalusia, Lemberg, Istanbul, Berlin, Sarajevo, Albania. May, as always, is Caucasus month, when we travel through Georgia’s and Armenia’s still largely unknown sights. At the end of September, we repeat our

Jewish heritage tour to Odessa through the shtetls of Galicia and Podolia, and in October the Toscan tour following the traces of Antal Szerb’s cult novel

Journey by moonlight, as well as the

tea-horse-road in China’s Yünnan province. Besides, we are planning new, exotic tours to

Ethiopia, Morocco, Southeastern Anatolia and

Saint Petersburg, as well as to the

North Russian monastery region, Kizhi and Solovki.I regularly hold presentations, historical and art historical lectures and travel reports on our tours, which are announced in the afore mentioned newsletter. Be sure to subscribe!

You can register for the tours or request information about them using the same

wang@studiolum.com address. In response, I will send you a detailed program with all pertinent information.

Usually, each participant pays for the flight ticket out of their own pocket, and everything else concerning the tour is organized by me.

Participation fees usually include one bed in a double room (breakfast included), rented bus and my services as guide; if any other expenses accrue, I will specify them. If you prefer a single room, ask me about the surcharge. Where I only indicate the participation fee approximately, it will depend on the number of participants and the corresponding final costs of the bus and hotels.

![]() 2020

2020![]() Sicilian round trip, 21-28 January.

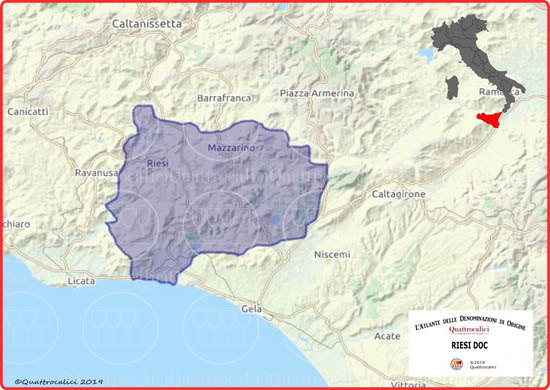

Sicilian round trip, 21-28 January. To bring spring forward, we begin with a few tours to warmer climes. During the one-week Sicilian round trip, we visit the most important sites of the island of many cultures – almost all World Heritage sites –, Catania’s fish market, Siracusa’s Greek old town and Jewish quarter, the valley of Agrigento’s ancient Greek temples, Cefalù’s Norman port and basilica, the Norman basilicas of Palermo and Monreale, decorated by Arab and Greek artists, the Greco-Roman theater of Taormina, and much more. • Travel by 9-seat minibus, participation fee 700 euros. •

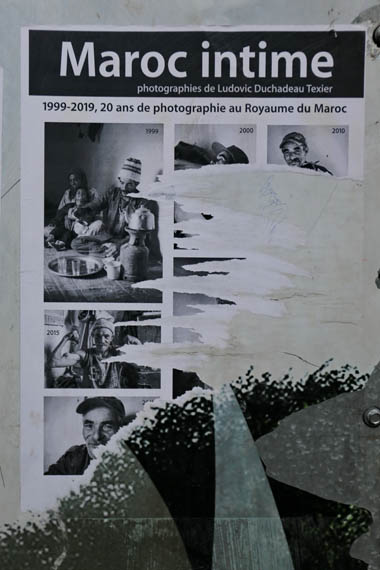

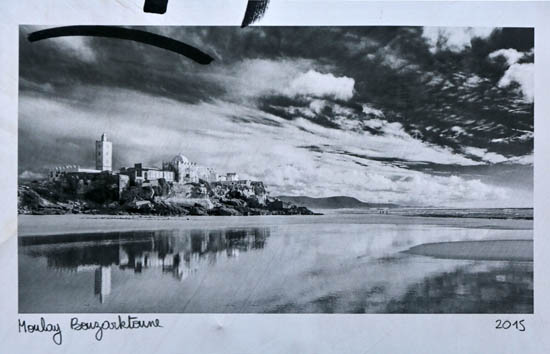

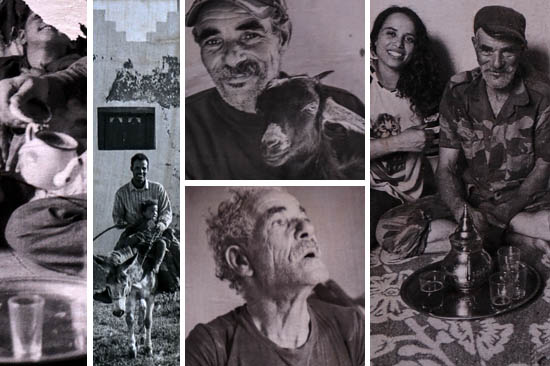

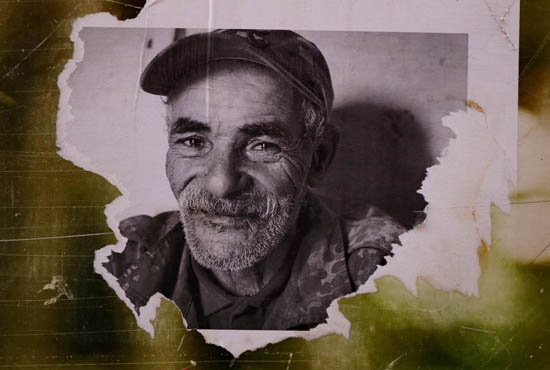

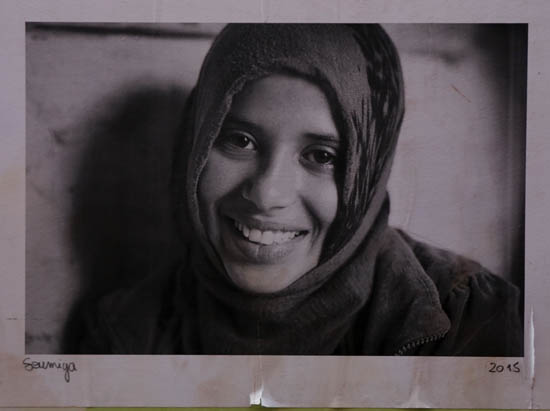

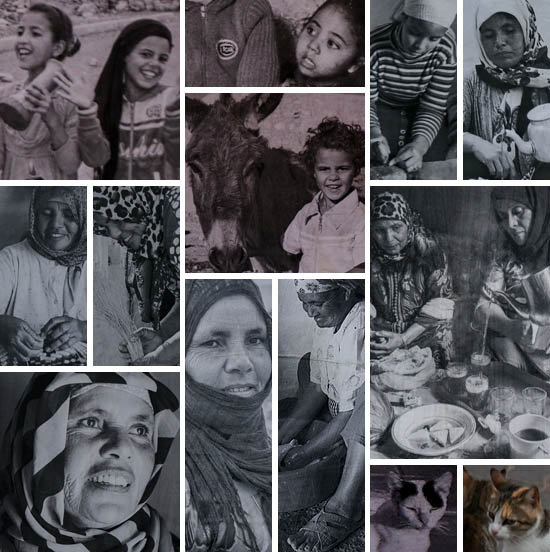

Full, but we will repeat it in March and December.![]() Marrakesh and the road of the kasbahs, 18-25 February.

Marrakesh and the road of the kasbahs, 18-25 February. From Marrakesh, Morocco’s former southern capital, thousand-year-old caravan routes lead through the river valleys of the High Atlas to the gold mines near the Equator, and these routes are bordered by majestic Berber clay fortresses,

kasbahs, and fortified towns,

ksars. In three days, we traverse the valleys of the Ounila, Draa and Ouarzazate rivers, and visit several kasbahs and ksars, paying special attention to the neighborhoods and legacy of the “Berber Jews” who lived here as merchants and silversmiths until the 1970s. The kasbah tour will be completed by a few days of sightseeing in Marrakesh, where the palaces, museums and other sights of the city will more deeply reveal the history of this region of many colors and cultural layers. • Participation fee 700 euros. •

Full, but, due to over-registration, we will repeat it in December.![]() Rome, from piazza to piazza, 2-6 March.

Rome, from piazza to piazza, 2-6 March. Following our previous successful

tours in Rome, we explore in detail the old town of Rome over the course of five days, including the most important ancient, Renaissance and Baroque monuments, also addressing some more “exotic” scenes, such as the Jewish quarter, the self-sufficient world of Trastevere, and the beautiful garland of ancient and medieval churches in the Caelius Hill. We acquaint ourselves with the city from square to square, street to street, so that it will offer many interesting details and secrets even to those who are already lovers of Rome. In addition, we visit the huge Raffaello exhibition, organized on the 500th anniversary of the master’s death. Our accommodations will be in the heart of the old town, in the Trastevere. For details, check

our posts on Rome. Participation fee 500 euros. •

Full, but if there are enough additional registrations, we will repeat it at the end of March.![]() Sicilian round trip, 7-14 March.

Sicilian round trip, 7-14 March. During the one-week round trip, we visit the most important sites of the island of many cultures – almost all World Heritage sites –, Catania’s fish market, Siracusa’s Greek old town and Jewish quarter, the valley of Agrigento’s ancient Greek temples, Cefalù’s Norman port and basilica, the Norman basilicas of Palermo and Monreale, decorated by Arab and Greek artists, the Greco-Roman theater of Taormina, and much more. • Travel by 9-seat minibus, participation fee 700 euros. •

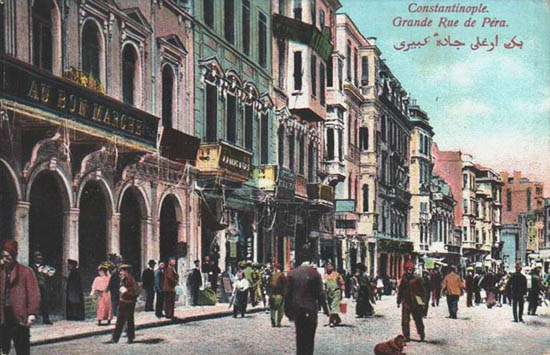

Full, but we will repeat it in December.![]() Istanbul, beyond the bazaar, 15-19 March.

Istanbul, beyond the bazaar, 15-19 March. We penetrate the many layers of the city’s two-thousand-year history, from the Roman and Byzantine period through the Ottoman Empire to modern Turkey. We explore in detail the most remarkable monuments from the Hagia Sophia to the Suleymaniye Mosque, walk through the self-sufficient neighborhoods from Galata to Kadiköy, and discover a lot of hidden places, small restaurants, Greek, Armenian, Jewish and Ottoman monuments. It is recommended that you read

our posts on Istanbul and

Turkish culture.• Participation fee 450 euros.

![]() Berlin scenes, 2-5 April.

Berlin scenes, 2-5 April. A long weekend to explore Berlin’s iconic sites and unknown parts, contemporary architecture and exotic neighborhoods. We visit the historic heart of the city as well as the recently built centers, the subcultural neighborhoods and little hidden worlds. We pay special attention to the cultural flourishing of Berlin of the 1920s with its Eastern European and Jewish immigrants, the post-war divisions, and the alternative scene of the 80s and 90s. • Participation fee 500 euros.

![]() Lemberg, 19-22 April.

Lemberg, 19-22 April. Lemberg/Lviv/Lwów is one of the most beautiful cities in Eastern Europe, and one which has not been demolished in the vicissitudes of the past hundred years. Several nationalities – Poles, Armenians, Jews, Ukrainians, Germans, Hungarians and others – have enriched it and made it one of the most colorful cities of the old Austrian Monarchy. Its architecture was as great during the Renaissance as it was during the Art Nouveau period. We visit this city over a long weekend. On the last day, we make a bus excursion to the

Baroque town of Drohobycz, the birthplace of Bruno Schulz, and the Jewish cemetery of Bolechów, one of the most beautiful and best-preserved Hasidic cemeteries in Galicia. • Participation fee 450 euros.

![]() Georgia round trip, 11-19 May.

Georgia round trip, 11-19 May. Every year we go to Georgia in May, when the mountains are already emerald green, and have not yet faded from the summer heat. Over the period of a week, we travel through almost every beautiful region of this extremely diverse country, from

Svaneti, the northernmost valley of the Great Caucasus, and the

fifteen-centuries-old residential towers of Ushguli through the medieval quarters of Tbilisi to the monasteries of the Kakheti wine region.

Here we have collected our posts on the Caucasus. • Participation fee 600 euros. •

This tour can be complemented with the following one into one large Caucasian round trip:![]() Armenia and Karabakh, 18-25 May.

Armenia and Karabakh, 18-25 May. We start from Kutaisi, and, turning south at Tbilisi, we enter Armenia through the northern mountains. By following the route of

our Armenian tour of four years ago, we visit above all the wonderful

Armenian monasteries, from Haghpat and Sanahin at the Georgian border through the churches along Lake Sevan to Tatev in the south and Khor Virap at the foot of Mount Ararat, and, on the way back, to

Bjni. We will see particular cemeteries, from the Armenian

Noratus through the Jewish Yeghegis to the Molokan

Bazarchay. We pass into romantic Karabakh, where we stop at hidden medieval churches as well as in

Shushi, the former capital of the region. After sightseeing in Yerevan, we return to Kutaisi.

Here we have collected our posts on Armenia. See also

the diary of our first travel to Armenia.• Participation fee 600 euros. •

Due to the large over-registration, we may have to lead this tour twice; if so, then the second one will be from 4 to 11 May.![]() Southeastern Anatolia from the Assyrian monasteries to Mount Nimrod, 27 May - 6 June.

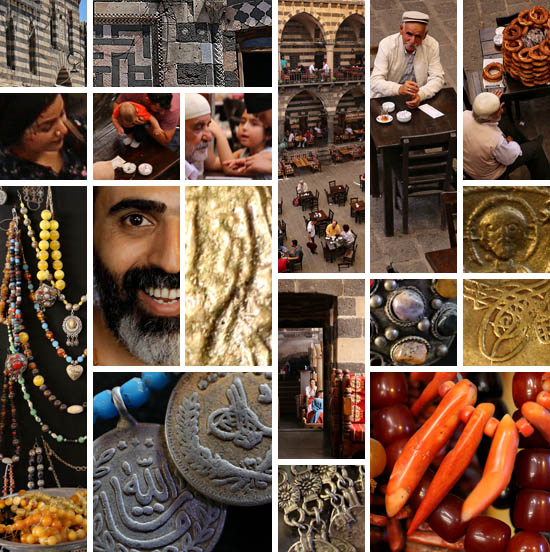

Southeastern Anatolia from the Assyrian monasteries to Mount Nimrod, 27 May - 6 June. The Turkish part of Northern Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and the Euphrates, is a vast mosaic of languages, religions, cultures and former empires from the Assyrians, Arameans, Persians and Greco-Romans to Syriac Christians, Armenians and Yezidis to today’s Kurds and Turks. Starting from the three-thousand-year old city of Diyarbakır, we take a bus tour through the white-stone medieval cities of Mardin and Midyat, the Assyrian monasteries of Tur Abdin, the supposed sites of Abraham’s life in Urfa and Harran, the largest museum of ancient mosaics in Gaziantep, and one of the wonders of the ancient world, the gigantic statues of King Antiochus’ tomb on Mount Nimrod.

The diary of our exploration tour can be read here.• Participation fee ca. 1000 euro.

![]() Catalonia, the cradle of Romanesque art, 11-18 June.

Catalonia, the cradle of Romanesque art, 11-18 June. We start our first Romanesque tour in Barcelona, with the exploration of the fascinating Romanesque frescoes and carvings collected in the National Museum. Then we go by bus to the Pyrenees, the valley of Boí, where every town and church is a World Heritage site. From there we

cross the mountain to South France, the medieval pilgrimage church of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges. • Travel with nine-seat minibus, participation fee 700 euro. •

Due to over-registration, we will repeat this tour in July.![]() Round trip in Scotland, 20-28 June.

Round trip in Scotland, 20-28 June. We tour the country by minibus from Edinburgh and back. We will visit fortresses, cathedrals and Renaissance castles, prehistoric stone circles and islands, whiskey distillers, we will sail on Loch Ness, and drive along one of the world’s most beautiful panoramic route, the North Coast 500. • Participation fee 800 euro. •

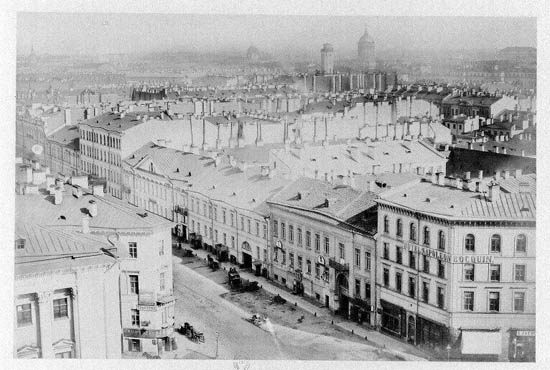

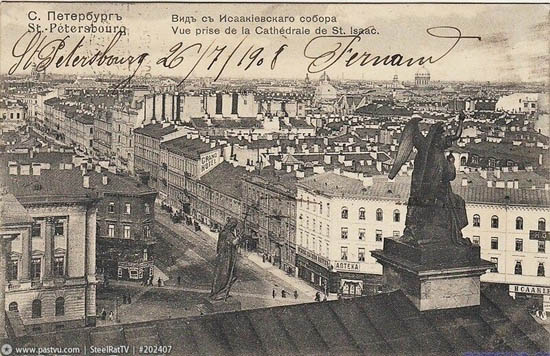

Due to over-registration, we will repeat this tour in July.![]() (Next year) St. Petersburg, end of June 2021, five days.

(Next year) St. Petersburg, end of June 2021, five days. Originally, we wanted to organize a St. Petersburg tour this year, but it turned out that in St. Petersburg there the good accommodations are so few and the tourist period is so short – only a few months – that for a larger group we have to book a year in advance. This is what we will do now, awaiting your registration for the year of 2021. Over five days, we do a thorough tour in the Northern Russian capital, from the memory of Peter the Great and Catherine to the architecture of Russian Art Nouveau and the Avantgarde, and we will also have an overview of Russian history, literature and fine arts embodied in the city. • Participation fee ca. 500 euro. •

The sightseeing can be also linked with the following tour:![]() (Next year) North Russian monastery region, Kizhi and Solovki, early July 2021, one week

(Next year) North Russian monastery region, Kizhi and Solovki, early July 2021, one week. We wanted to organize this tour for 2020, too, but the lack of good accommodations and the narrow period of visitation are especially true for the Russian North, while there is a great domestic and international interest in the monasteries. Therefore we also organize this tour a year in advance, looking for your registrations for 2021. From St. Petersburg, we take a bus across Karelia to the White Sea, the Solovetski Island, one of the holiest monastery complexes of Russian orthodoxy, which until recently was an inaccessible closed area. Along the way, we visit Old Ladoga, one of the centers of ancient Rus, as well as the wooden monasteries of Kizhi, on the island of Lake Onega. Meanwhile we get an overview of the history of Russian orthodoxy and monasticism, Russian religious art and icons. • Participation fee ca. 900 euro. •

For the two Russian tours, send your application before 6 February 2020, because then I will go there to negotiate and book.![]() Photo tour in Kevsureti, 29 June – 5 July

Photo tour in Kevsureti, 29 June – 5 July Khevsureti is the northernmost, closed region of Georgia, along the Georgian military road, where, according to many authors, you can still find the descendants of the Frank crusaders who supported medieval Georgian kings. After the other “roofs” of the Caucasus –

Ushguli,Tusheti,Xinalik,Dadivank– now we lead a small photo tour here. From Tbilisi, we go up with an off-road vehicle to the fortress of Shatili on the Chechen border, from where we traverse this beautiful region of the Georgian Caucasus, accessible only in the summer. • Participation fee 1000 euro. •

Full![]() Adventure tour in Georgia, 6-13 July.

Adventure tour in Georgia, 6-13 July. In contrast to the Georgian round trip in May, in which we travel comfortably by bus through the most beautiful regions of the country, on this tour we invite our more adventurous readers. From Tbilisi, we take off-road vehicles up to one of the most archaic and least accessible regions of the country, the valleys of Tusheti under the Chechen-Daghestani border mountains of the Greater Caucasus. Here, we visit the archaic fortified towns on horseback, but if you want, you can also come with us on jeeps. Then we go rafting on Rioni river from Ambrolauri almost to Kutaisi. To participate, you need no previous training in riding or rafting, we will get and learn everything necessary locally.

Here you can read our travelogue of Tusheti, and

here our collected posts on Georgia and the Caucasus.• Participation fee, which includes all equipment and full provisions, 700 euro.

![]() Catalonia, the cradle of Romanesque art, 14-21 July.

Catalonia, the cradle of Romanesque art, 14-21 July. We start our first Romanesque tour in Barcelona, with the exploration of the fascinating Romanesque frescoes and carvings collected in the National Museum. Then we go by bus to the Pyrenees, the valley of Boí, where every town and church is a World Heritage site. From there we

cross the mountains to South France, the medieval pilgrimage church of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges. • Travel by nine-seat minibus, participation fee 700 euro.

![]() Round trip in Scotland, 23-31 July.

Round trip in Scotland, 23-31 July. We tour the country by minibus from Edinburgh and back. We will visit fortresses, cathedrals and Renaissance castles, prehistoric stone circles and islands, whiskey distillers, we will sail on Loch Ness, and drive along one of the world’s most beautiful panoramic route, the North Coast 500. • Participation fee 800 euro.

![]() Subotica Art Nouveau, 13-15 August.

Subotica Art Nouveau, 13-15 August. In

one of the most important centers of Hungarian Art Nouveau (now in Serbia), we visit

one of the most beautiful synagogues of pre-war Hungary as well as the gorgeous town hall – both

chef d’oeuvres of

the Marcell Komor - Dezső Jakab architectural duo–, and the entire old town, which, in late 19th century, became one of the most exciting architectural centers of the country. On the way there, we stop at the most beautiful old Hungarian library, of the Archdiocese of Kalocsa, where I did research for many years, and on the way back, in the Art Nouveau Spa of Palić, whose buildings were also designed by Komor and Jakab.

See our posts on Szabadka/Subotica here.• Travel from Budapest by bus, participation fee 250 euros.

![]() Long weekend in Sarajevo, 16-19 August.

Long weekend in Sarajevo, 16-19 August. The original Persian-Ottoman name of Sarajevo, located in the high mountains of Bosnia, is Saray Bosna, “the Bosnian caravanserai”, and it really feels like time has stopped since the centuries of the Ottoman Empire. In the vast bazaar and in the tortuous streets of the mountain slopes, full of small mosques, Ottoman cemeteries and old houses, the atmosphere of the Ottoman period is still so present, to an extent which persists not even in Turkey. At the same time, during the period of the Austrian Monarchy, a beautiful Art Nouveau district was added to the old town, and the city was one of the intellectual centers of the former Yugoslavia. Today, Sarajevo has largely recovered from the destruction of the siege of 1992-1996, and it is considered to be one of the most important centers of contemporary architecture in the Balkans. During our long weekend, we explore this unique ensemble, and make a one-day bus trip through the wonderful valley of Neretva River to Mostar. • Participation fee 350 euros.

![]() Unknown Albania, 22-29 August.

Unknown Albania, 22-29 August. In this unexplored country, we first visit the least known – because it has only recently been provided with an asphalt road – part, the northern mountains, the valleys of Theth and Valbona. We sleep in traditional farm houses converted into modern family pensions, and we make a long boat tour on the Drin river among the mountains. We visit the Ottoman merchant town of Berat, and the ancient Greek settlements of Byllis and Apollonia. We make a detour to Kosovo, to the beautiful Serbian monastery of Dečani and the Ottoman town of Prizren, and finish our journey at the pristine bay and beach at Vlora, next to the monastery of Zvernets. Our Albanian posts

are available here. Participation fee 600 euros.

![]() Iran’s historic cities, 4-14 September.

Iran’s historic cities, 4-14 September. We have postponed our spring Iranian tours, due to the tense political situation, but we hope that by autumn, peace will be restored in the Middle East. Therefore, you can register for the two autumn Iran tours on the condition that you will send your final decision at the end of May, in light of the actual political situation. First, as in every year, we travel along the axis of the most important historical cities, from

Kashan through

the formerly Zoroastrian town of Abyaneh, Isfahan, Pasargade and Persepolis to Shiraz, from where we return by domestic plane to Tehran. • Participation fee 1200 euro. •

This tour can also be linked with the following one:![]() Iran, the ancient desert settlements, 15-21 September.

Iran, the ancient desert settlements, 15-21 September. The

Iranian desert, as we wrote, is not dead at all, but a particularly beautiful region of the country. Thanks to the underground water channels, it is permeated by dense networks of thousand-year-old settlements, caravanserais and trade routes, which have played an important role in the history of Iran. We follow this network in the triangle of the historical towns of Kashan, Yazd and Isfahan, by visiting ancient Zoroastrian and Jewish settlements, clay fortresses of imposing height, and sleeping in lonely caravanserais in the middle of the desert, under a seldom-seen starry sky. This tour greatly contributes to the understading of how the Iranians see their own country. • Participation fee 900 euro.

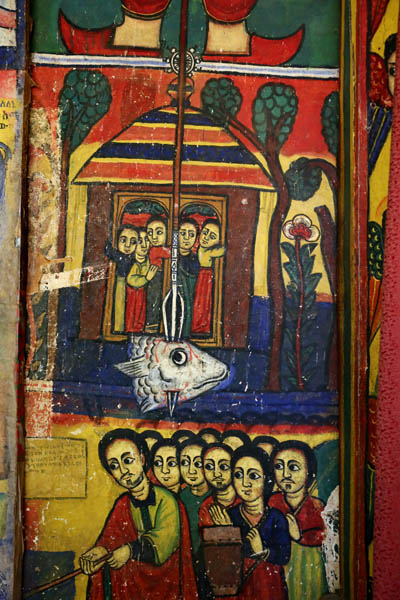

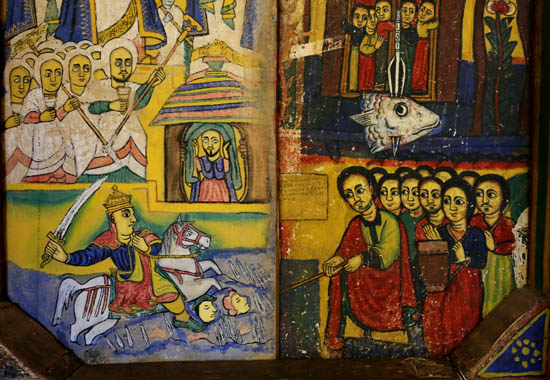

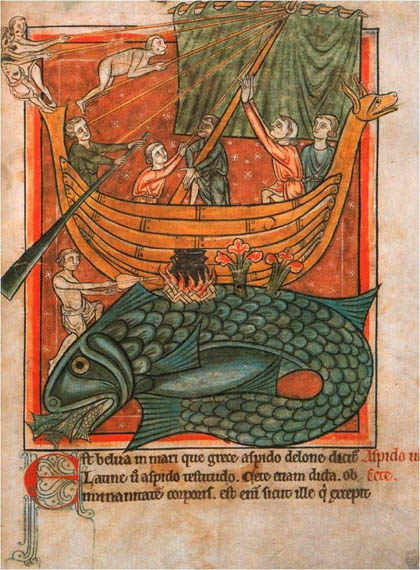

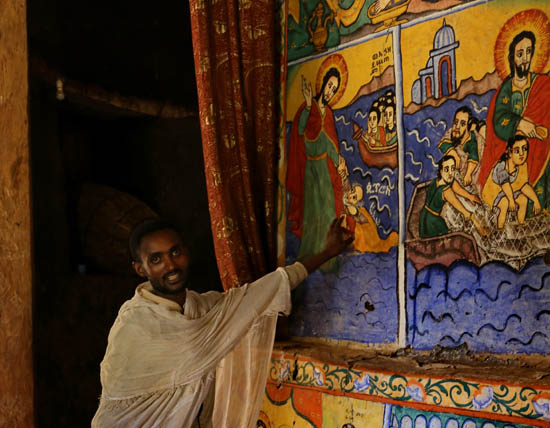

![]() (Next year) Ancient monasteries of Ethiopia, end of September 2021, ten days.

(Next year) Ancient monasteries of Ethiopia, end of September 2021, ten days. This year, there have been not enough participants to stage this trip, so we announce it for next year to provide ample time to consider it. Ethiopia was among the first countries to embrace Christianty as a state religion, and, beginning in the sixth century, the Abyssinian highlands developed a rich monastic life. We primarily visit these ancient monastic regions, from the islands of Lake Tana through Axum, showing the impact of Egyptian culture, and the cave monasteries of Tigray, to the magnificent monastic complex of Lalibela, carved deep into the rocks. But we also go to see the Renaissance capital in Gondar and the villages of Ethiopian Jews, and trek in the fascinating Simien Mountains (almost all World Heritage sites).

Here we reported about our first, preparatory Ethiopian trip, and

here we wrote about the iconography of the Ethiopian churches. • Participation fee ca. 1300 euro, which also includes several domestic flights.

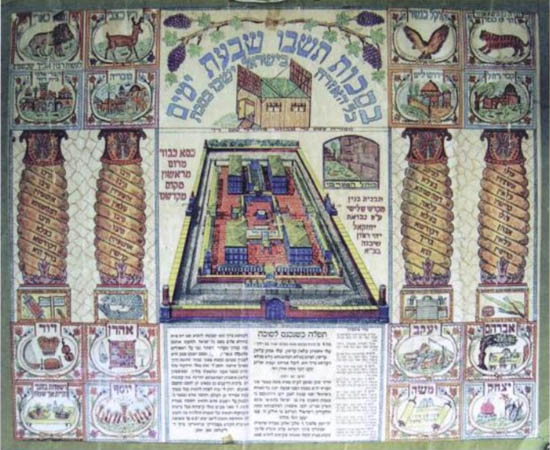

![]() Odessa and the South Galician world of the shtetls, 23-30 September.

Odessa and the South Galician world of the shtetls, 23-30 September. The great

tour de force that we do every other year, inspired by Jonathan Safran Foer’s

Everything is illuminated. A three-day trip by bus through the important – and partly still living – Jewish settlements of the former Polish-Russian region,

Czernowitz,Kamenets-Podolsk,Uman, Mezhibozh, the cradle of Hasidism, and many other Hasidic towns and cemeteries, down to Odessa, where we discover, in the wake of Isaac Babel, the sophisticated culture of the “Paris of the South” and the memories of the former Jewish gangster’s world in the

Moldavanka. From Odessa, we return home by plane. We have collected our posts

on Odessa here, and our writings on

the Jewish heritage here.• Participation fee 600 euros. •

If you wish, on the way back we can stop for a day’s sightseeing in Kiev.![]() The route of Journey at moonlight from Venice through Umbria to Tuscany, 3-10 October.

The route of Journey at moonlight from Venice through Umbria to Tuscany, 3-10 October. In this one-week tour – which on its first being announced in 2016, was considered as the best Río Wang tour of the year – we follow the path of Antal Szerb’s

1937 cult novel, considered by

Nicholas Lezard as “one of the greatest works of modern European literature.” From Venice, we travel by bus through Ravenna, Urbino, Umbria and Tuscany, Gubbio, Assisi and Arezzo, the centers of early Renaissance art, to as far as Siena and San Gimignano. During the journey, like the figures of the novel, we encounter the surviving traditions of the pre-Christian world, the many thousand-year-old Oscan towns built on hilltops, the magnificent view of the Apennines, and the renowned “Sienan primitives.” • Participation fee 700 euros, including several dinners.

![]() Tuscan round trip, 10-17 October.

Tuscan round trip, 10-17 October. We

have followed several times with great success the route of Antal Szerb’s

Journey by Moonlight from Venice through Urbino and Umbria, Gubbio, Assisi and Arezzo to Siena, individually identifying the sites of the novel. This year, we follow our route westward, to get to know what Mihály would have seen, had he not given up wandering at the end of the novel. We will see Etruscan and Roman monuments, hilltop towns, fascinating examples of early Renaissance painting, and magnificent views of the Tuscan hills. • Participation fee 700 euros.

![]() A long weekend in Florence, 17-21 October.

A long weekend in Florence, 17-21 October. A detailed art historical and historical tour in the capital of the Renaissance and the cradle of the Medici House. We visit the most important monuments in the triangle of the Duomo, the Signoria and the Santa Croce and beyond, the left bank of Arno, the churches, palaces, squares and historical sites, everywhere explaining in detail the history and history makers, art and artists. • Participation fee 500 euros.

![]() Journey along the tea-horse-road in Yünnan province, China, 30 October – 8 November.

Journey along the tea-horse-road in Yünnan province, China, 30 October – 8 November. Three years ago, we started with this tour to explore China, with whose language and culture

I have been engaged for a quarter of a century. In 2017, this was our most successful tour. Our road leads through one of the most beautiful and most archaic regions of China, rich in historical monuments and natural beauties, the region of Yünnan under the Tibetan mountains, homeland of Chinese tea, and the towns of several ethnic groups. Picturesque tea lands and rice terraces, deep canyons and still untouched historic towns (check the photos of my

Yünnan guide, purchased there about ten years ago).

Read the description of our 2018 tour here.• Participation fee 1300 euros.

![]() Sicilian round trip, 28 November – 5 December.

Sicilian round trip, 28 November – 5 December. During the one-week round trip, we visit the most important sites of the island of many cultures – almost all World Heritage sites –, Catania’s fish market, Siracusa’s Greek old town and Jewish quarter, the valley of Agrigento’s ancient Greek temples, Cefalù’s Norman port and basilica, the Norman basilicas of Palermo and Monreale, decorated by Arab and Greek artists, the Greco-Roman theater of Taormina, and much more. • Travel by 9-seat minibus, participation fee 700 euros.

![]() Marrakesh and the road of the kasbahs, 9-16 December.

Marrakesh and the road of the kasbahs, 9-16 December. From Marrakesh, Morocco’s former southern capital, thousand-year-old caravan routes lead through the river valleys of the High Atlas to the gold mines around the Equator, and these routes are bordered by majestic Berber clay fortresses,

kasbahs, and fortified towns,

ksars. In three days, we traverse the valleys of the Ounila, Draa and Ouarzazate rivers, and visit several kasbahs and ksars, paying special attention to the neighborhoods and legacy of the “Berber Jews” who lived here as merchants and silversmiths until the 1970s. The kasbah tour will be completed by a few days of sightseeing in Marrakesh, where the palaces, museums and other sights of the city will more deeply reveal the history of this region of many colors and cultural layers. • Participation fee 700 euros.

![]() Historic cities of Andalusia, 17-21 December.

Historic cities of Andalusia, 17-21 December. Andalusia is one of those special sites of the Mediterranean, on which many great cultures left their mark. Starting from Málaga, we go through the historic cities of Seville, Córdoba, Granada and Ronda, getting to know in detail their Roman, Arabic, Jewish and Christian past, monuments and still living traditions. • Participation fee 700 euros.

Whenever we announce a tour in detail, and when we include a new tour in this calendar, we will also send out a circular e-mail, for which it is worth signing up at

wang@studiolum.com.

![]()

¿Quiénes son estos tres jinetes que escalan la puerta románica de bronce de la catedral de Pisa? Es obvio: los Tres Reyes Magos. Lo decimos sin titubear aunque, si los miramos bien, ningún atributo lo señala: no hay estrella ni pesebre alguno. En nuestra cultura, este perfil característico de tres jinetes cabalgando en fila se ha convertido en un topos visual indiscutible que evoca a los Tres Reyes incluso cuando se trate de algo completamente diferente.

¿Quiénes son estos tres jinetes que escalan la puerta románica de bronce de la catedral de Pisa? Es obvio: los Tres Reyes Magos. Lo decimos sin titubear aunque, si los miramos bien, ningún atributo lo señala: no hay estrella ni pesebre alguno. En nuestra cultura, este perfil característico de tres jinetes cabalgando en fila se ha convertido en un topos visual indiscutible que evoca a los Tres Reyes incluso cuando se trate de algo completamente diferente.

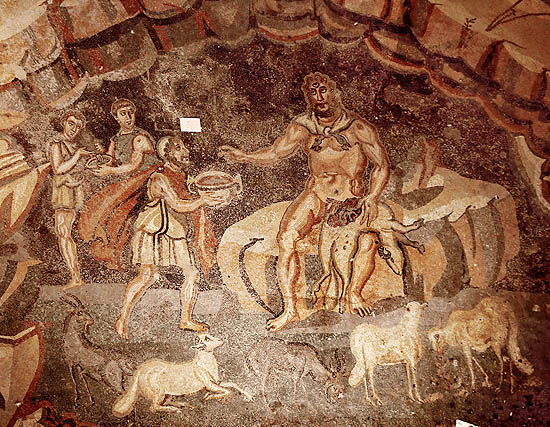

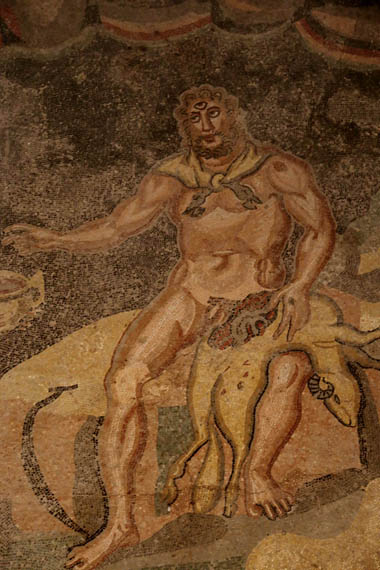

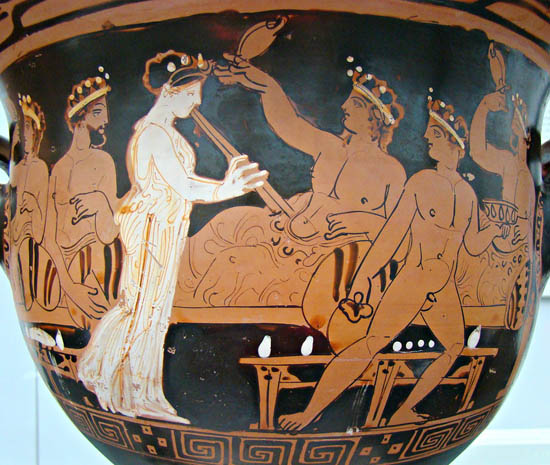

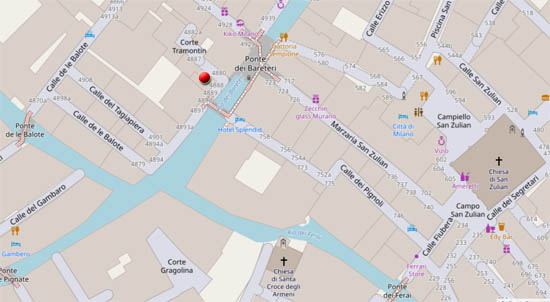

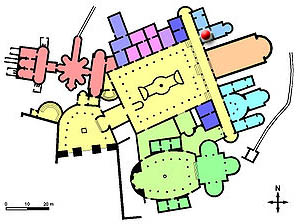

All of these will be discussed in a future post. Now I just want to talk about the scene decorating one of the dominus’ suites. To be exact, the antechamber of the domina’s bedroom (marked with a red dot on the floor plan). This mosaic shows a story that you do not want to dream about. It is the episode from the Odyssey where the Greeks venture into the giant cave of the one-eyed Polyphemus – which is known to have been in Sicily –, and the terrible cyclops begins to devour them. Then Odysseus walks up to him, offering him a large jug full of night-colored wine, and, having made him drunk, puts out his single eye with a sharpened and heated stick.

All of these will be discussed in a future post. Now I just want to talk about the scene decorating one of the dominus’ suites. To be exact, the antechamber of the domina’s bedroom (marked with a red dot on the floor plan). This mosaic shows a story that you do not want to dream about. It is the episode from the Odyssey where the Greeks venture into the giant cave of the one-eyed Polyphemus – which is known to have been in Sicily –, and the terrible cyclops begins to devour them. Then Odysseus walks up to him, offering him a large jug full of night-colored wine, and, having made him drunk, puts out his single eye with a sharpened and heated stick.