![]()

Almost a year ago I already wrote some

apologetic rambling on why I do not write so often. One justification is that too often while collecting materials for the next story I stumble upon many side stories. Following a new thread you collect more information, more images and documents, as well as make new inquiries. As a result, similar to

Achilles in

Zeno’s

paradox, you never seem to catch the end of your journey for the ultimate story. Here is one of such side stories, which emerged with a wartime photo I found while preparing the story of soldier letters sent in 1941 that never made it home.

Who is on the photo?

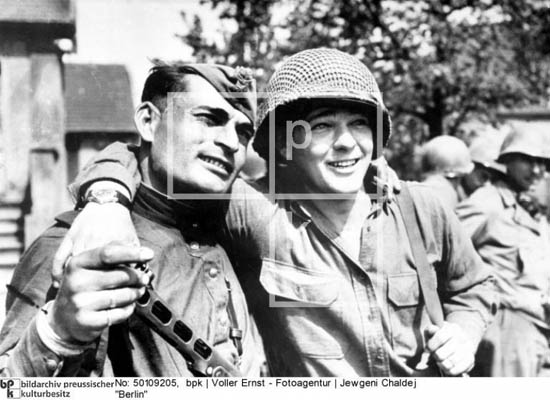

I came across this photo almost two years ago, in a German photo-archive just by searching for “Aserbaidschan” i.e. “Azerbaijan”. The photo by a world famous author of many iconic World War Two photos,

Yevgeny Khaldei (1917-1997) has a short title – “Berlin”. The date indicated is July 1945 – the time when American, British and French troops were let into agreed sectors of Berlin, captured by the Soviet Army.

If you pay attention to the uniforms, it is obvious that the image is a mirror inversion. The description reads as “Zwei Soldaten, ein amerikanischer und ein russischer aus Aserbaidschan.” i.e. “Two soldiers, one American and one Russian from Azerbaijan”. It does not reveal the names of the two soldiers, so in this case it is hard to say if “Russian” should be read as “Soviet”.

Searching internet you will find the same photo, accompanied by two different captions that contain exact names of those who are on the photo.

The Soviet soldier is described as

Ivan Numladze, bearing a Georgian surname. The

online database of documents on Great Patriotic War awards and battle documents of the Ministry of Defense of Russia did not return any result on my search for this surname. It is not strange since the database is not complete yet. But their online archive of “irretrievable losses” returned one person:

Grigoriy Numladze, who was freed from captivity in Romania in October 1944.

Confusion starts with the name of the American soldier indicated either as

Buck Kotzebue or as

Byron Shiver. But the date and place are the same – April 1945, somewhere near Torgau, Germany, where 1

st American Army and 5

th Soviet Guards Army

linked up at Elbe River.

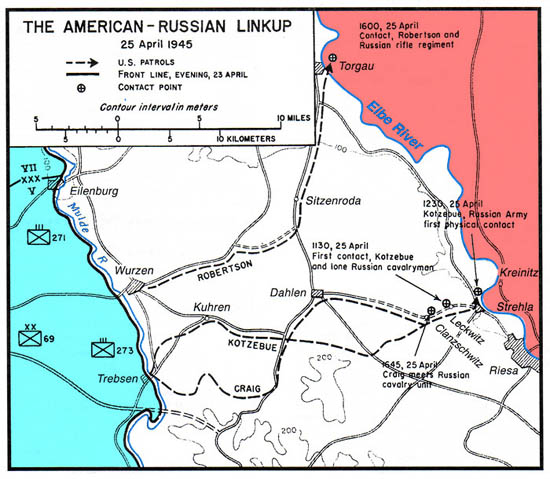

First Lieutenant

Albert L. ‘Buck’ Kotzebue of the Company G of the 273

rd Infantry Regiment was leading one of the three American patrols that made contact with the Soviet troops on 25 April 1945.

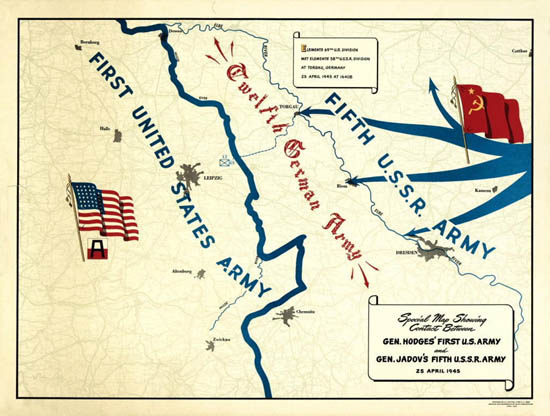

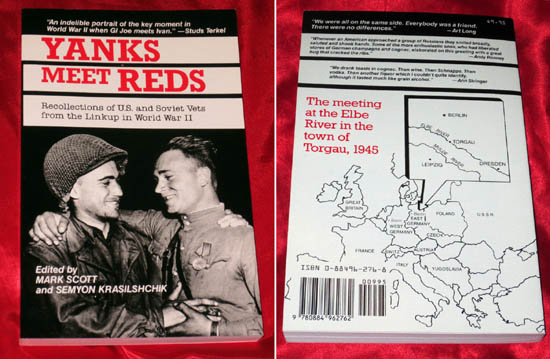

![]()

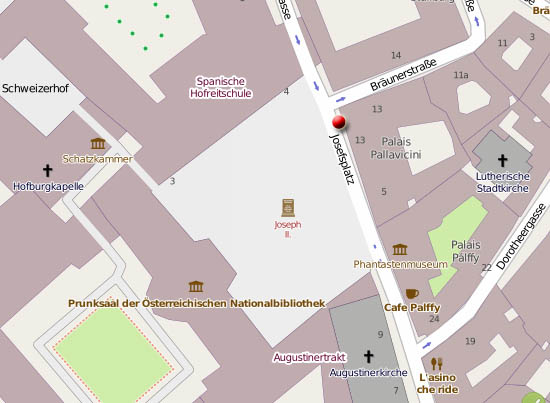

The above map shows roughly the place and time, when the second patrol led by 2nd Lieutenant

William D. Robertson of the same regiment met the Soviet patrol led by Lieutenant

Alexander Silvashko (1922-2010) of the 58

th Guards Division – on a damaged bridge over the Elbe in Torgau. By a twist of fate, back then exactly this meet up became the ‘official’ one in the West, and

a photo of these two officers, taken by an American photographer, became the symbol of the Elbe linkup. The same image was chosen for the cover of the book published in 1988, both in the US and the USSR, with different titles. “Yanks meet Reds” in English and “Встреча на Эльбе” (Meeting at the Elbe)

in Russian contains recollections of veterans from both sides of the Elbe. There was also a third patrol led by Major

Fred W. Craig, which was sent to find out what is up with

Kotzebue’s patrol that left a day earlier.

![The cover of the book “Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II”. Capra Press, August 1988. Source: ebay.com]() The cover of the book Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II, Capra Press, August 1988. Source: ebay.com

The cover of the book Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II, Capra Press, August 1988. Source: ebay.comSo, later investigation showed that the first contact was in fact made by

Kotzebue’s patrol. On their way from Kuhren to Strehla, at around 11:30 they met a “Russian” cavalryman at a farmhouse courtyard in Leckwitz. This was actually an ethnic Kazakh, Private

Aytkali Alibekov conscripted in 1943 from

Tashtagol District of Russia. The patrol got some directions from him, he also advised to take a freed Polish prisoner of war as a guide. The major encounter happened some hour later with the Soviet company under command of Lieutenant

Grigori Goloborodko of the 175

th Guards Rifle Regiment.

Apparently there is no publicly available photo evidence of this first meeting. But US Army artist

Olin Dows (1904-1981), who later witnessed the meeting of allied forces, depicted the moment in one of his paintings with this not quite accurate description of the event:

“At 11:45 on the morning of April 25, 1945, from the Strehla bank of the Elbe River, Lt Kotzebue fires two red and green flares from a carbine as a signal of identification to the Russians on the opposite bank. Below is the boat which he and five men from his patrol used to reach the Russian side. In the background is the drifting German pontoon bridge which has been knocked away from its moorings by shell fire and the mixed German military and civilian convoy which was trying to cross the Elbe when destroyed by Russian tanks.”Going back to the initial photo of two soldiers, the American depicted on it apparently is not

Kotzebue. First, because he is not a lieutenant, besides on other rare photos

Kotzebue looks quite different with his binoculars, wearing a jacket and smoking a pipe.

So, the young American soldier with a shining smile is Private

Byron Shiver,

native of Florida, from the same company, who was part of the

Kotzebue’s patrol. He appears in some other photos, taken during the subsequent meetings the day after.

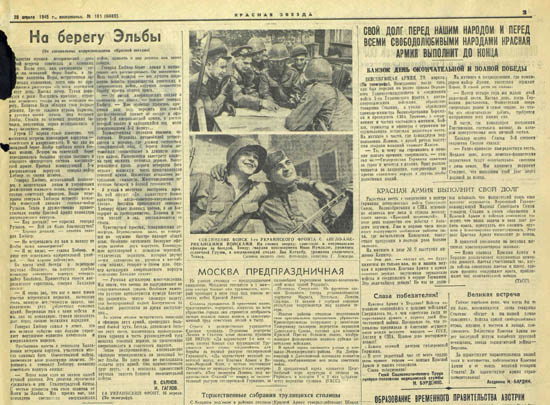

It seems that the cause of this confusion is the photo caption that appeared in the 29 April 1945 issue of the official newspaper of the People’s Commissariat for Defense of the USSR

Красная Звезда (Krasnaya Zvezda/Red Star). The bottom photo at page 3 obviously shows the same scene with two soldiers from a different perspective. The caption read as: “THE LINK UP OF THE TROOPS OF THE 1

ST UKRAINIAN FRONT AND ANGLO-AMERICAN FORCES. On the picture above: Soviet and American officers chatting. Below: The Red Army guardsman

Ivan Numladze, a native of sunny Georgia, and the American soldier

Buck Kotzebue, a native of sunny

Texas. Pictures by our special photo-reporter Captain

G. Khomzor.”

Indeed, Lieutenant

Kotzebue was native of Houston, Texas. An interesting fact is that he believed that his ancestors were loyal subjects of the Russian Empire, ethnic Baltic Germans. Captain

Otto von Kotzebue (1787-1846) was famous for his explorations of Alaska – there is a city and a sound named after him there. Perhaps,

Kotzebue was chosen for the caption because of the familiar ‘sunny Texas’ cliché, and

Numladze may well be a curtsey to the Comrade Stalin, also ‘native of sunny Georgia’.

That would not be strange – for a long time official Soviet version credited Georgian Jr. Sergeant

Meliton Kantaria and Russian Sergeant

Mikhail Yegorov for

raising the first Soviet flag over the Reichstag. In fact, a red flag was raised as early as the night of 30 April by a small group of volunteers, which included Sergeant

Mikhail Minin, Sr.Sergants

Gazi Zagitov,

Alexandr Lisimenko, and Sergeant

Alexei Bobrov. The papers show that they were recommended for the

Hero of the Soviet Union decoration, but got a lower rank

Order of the Red Banner.

Poemas del río Wang already wrote in the

“Soviet Capa” about the iconic photo “The flag of victory over the Reichstag” by

Khaldei. For a long time it was widely unknown that the photo actually

is staged and people on the photo are Private

Alexei Kovalyov from Ukraine and Sergeant

Abdulhakim Ismailov from Dagestan. Now it is also known that the photo was retouched to remove a ‘second watch’ from

Ismailov’s right wrist as this could cause questions about looting. By the way, apparently the Soviet soldier in the ‘two soldiers’ photo has got two rings on his left hand.

All in all, the question was still open for me – is it ‘

Numladze, a native of sunny Georgia’ or a soldier ‘from Azerbaijan’? On 4 February 2014, I finally thought why not to send an

email and ask the photo agency.

Dear Sir/Madam

First of all, I would like to thank you for your noble work of storing historical images and making them available through your online services. My request concerns a famous 1945 photo, which is also stored in your archives:

The caption in German says: “Two soldies, one American and one Russian from Azerbaijan.” Fotograf: Jewgeni Chaldej / Zwei Soldaten, ein amerikanischer und ein russischer aus Aserbaidschan. / Aufnahmedatum: Juli 1945 / Aufnahmeort: Berlin / Inventar-Nr.: 1191. I wonder if your colleagues could give more insight about what was the origin of this caption.

The reason for this request is that other sources give different captions - for example http://victory.rusarchives.ru/index.php?p=31&photo_id=389 It says “Soldier of American Army Buck L. Kotzebue and Red Army soldier Ivan Numladze at the moment of meeting on Elbe. – Солдат американской армии Бак Л. Кацебу и красноармеец Иван Нумладзе в момент встречи на Эльбе.” In fact, this caption is not accurate at least about the American soldier, since he is U.S. Army Private Byron Shiver of the 273rd Infantry Regiment.

Any additional information on the matter would be very much appreciated. I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Many thanks, Araz

I received a short answer the day after:

Dear Sir

Thank you for your message. bpk distributes digital images by Chaldej on behalf of the agency Voller Ernst http://ernstvolland.de/en

I presume it’s the photographer’s original caption. We don’t have further information on the portrayed soldiers.

Best regards, Jan Böttger

A man with a camera

Further explorations revealed that my question may not be the right one. It seems that the meetings initiated by

Robertson’s patrol are covered solely by American photo-reporters, while Soviet photographers were shooting mainly the meetings at the East side. Who were these photo-reporters, was

Khaldei among them?

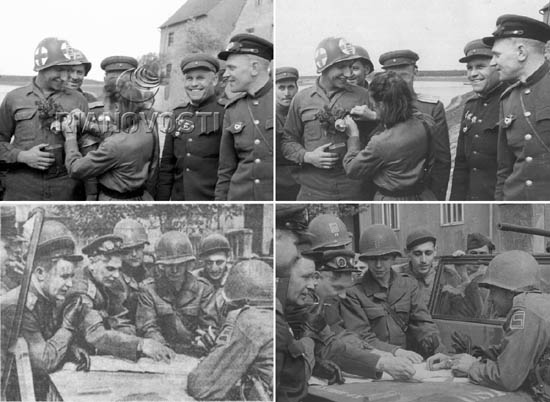

![A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA Novosti]() A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA Novosti

A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA NovostiOne was obviously the special photo-reporter of

Krasnaya Zvezda Captain

Georgiy Khomzor (1914-1990). The photo of ‘two soldiers’ is most probably taken by him, since a very similar photo above is also credited to him. It is strange though that

Khomzor’s photo, published in

Krasnaya Zvezda with the caption that mentions

Kotzebue and

Numladze, was taken from a totally different angle.

Actually his surname is

Khomutov, but during his early career as a retoucher he was signing his works with “Хом. 30 р.” meaning “Khom(utov). (Price: )30 r(ubles)”. This looks like “ХомЗОр” i.e. “Khomzor”, so this pseudonym stack to him. This frontline photo-reporter quickly earned great popularity during the war. Executive editor of “Krasnaya Zvezda”

David Ortenbergremembers that when in May 1945 he was recommended for

Order of the Patriotic War 2

nd class decoration, the commander of the 1

st Ukrainian Front Marshal

Ivan Konev (1897-1973)

corrected the list and changed it to a higher rank Order of the Red Banner. The section titled “the brief, concrete description of personal feat of arms or merits” in the decoration paper mentions that “At the Elbe River, he was photographing the historical meeting of the troops of the 1

st Ukrainian Front with the American Army”.

![A rare photo showing Lieutenant Kotzebue smoking his pipe by Khomzor. Source: RIA Novosti]() A rare photo showing Lieutenant Kotzebue smoking his pipe by Khomzor. Source: RIA Novosti

A rare photo showing Lieutenant Kotzebue smoking his pipe by Khomzor. Source: RIA NovostiDespite of this, today there is not even a Wikipedia page dedicated to him or a photo of him in the Internet to identify if the man with a camera on the picture below is

Khomzor. Judging by his decoration he is not, it is not clear either if he is Captain or Sr. Lieutenant. The decorations on the person’s uniform match better Captain

Alexandr Ustinov (1909-1995), photo-reporter of

Pravda newspaper, who by July 1944 was already awarded

Medal “For Courage” and

Order of Red Star. But unlike this man

Ustinov had a splendid chevelure, and his medal must have been of old 1939-1943 version with a

short mount.

![A photo of the same scene, taken by American Private Igor Belousovitch who was in Major Craig’s patrol (Craig is the leftmost American – they all put helmets on), shows most probably Ustinov working. Source: The Moscow Times]() A photo of the same scene, taken by American Private Igor Belousovitch who was in Major Craig’s patrol (Craig is the leftmost American – they all put helmets on), shows most probably Ustinov working.

A photo of the same scene, taken by American Private Igor Belousovitch who was in Major Craig’s patrol (Craig is the leftmost American – they all put helmets on), shows most probably Ustinov working.

Source: The Moscow TimesThis photo was in the album

Ustinov presented to the veterans including

Silvashko, who after the war was a village school director and history teacher in Kletsk district in Belorussia.

Silvashko later presented it to the Kletsk city museum and the scanned images appeared in the Internet.

Kotzebue in his recollections mentions that one of the first three “Russian”s they met at the Elbe River was a photographer in the ranks of Captain, who took their photos. This must be

Khomzor, since

Ustinov writes in his memoirs

С «лейкой» и блокнотом (With ‘Leica’ and notebook) that he arrived at the Elbe River crossing only on 26 April. He also mentions that “Later a large group of American journalists, cameramen and my colleagues – photo-reporters got over to our side. Among Soviet reporters were

Konstantin Simonov,

Sergey Krushinski from

Komsomolka, and

Georgiy Khomzor– photo-reporter of

Krasnaya Zvezda”. Interestingly, many sources, including

Ustinov’s daughter claim that

Ustinov was “the only Soviet photo-reporter, who witnessed the meeting at the Elbe”.

By the way, the title of the book “With ‘Leica’ and a notebook” is taken from a popular “Song of the war reporters”, written by

Konstantin Simonov (1915-1979) and composed by

Matvey Blanter (1903-1990) – the composer of the famous

“Katyusha”.Simonov wrote it in 1943 as

“Reporters’ drinking song”, but some words were censored for the popular official version.

От Москвы до Бреста

Нет такого места,

Где бы ни скитались мы в пыли,

С “лейкой” и с блокнотом,

А то и с пулеметом

Сквозь огонь и стужу мы прошли. | From Moscow down to Brest

There is no such a place,

Where we did not wander in the dust.

With “Leica” and a notebook,

And sometimes with machine gun

The fire and the frost we passed through. |

(Жив ты или помер –

Главное, чтоб в номер

Материал успел ты передать.

И чтоб, между прочим,

Был фитиль всем прочим,

А на остальное - наплевать!) | (Be you alive or dead –

Main thing: for this issue

You would pass materials on time.

By the way, let it be

A wick to all others,

As for other things - don’t give a damn!) |

Без глотка, товарищ,

(Без ста грамм, товарищ,)

Песню не заваришь,

Так давай за дружеским столом

(Так давай по маленькой хлебнем!)

Выпьем за писавших,

Выпьем за снимавших,

Выпьем за шагавших под огнем. | Without a toothful, comrade,

(Without a half-pint/100-gram, comrade)

A song one would cook hardly,

Around a friendly table let us have

(Come on, let us gulp down it bit by bit!)

A drink to who were writing,

A drink to who were filming,

A drink to who were marching under fire! |

Есть, чтоб выпить, повод -

За военный провод,

За У-2, за “эмку”, за успех...

Как пешком шагали,

Как плечом толкали,

Как мы поспевали раньше всех. | For drink we have a reason

To military farewell,

To U-2, to the “M’ka”, to success…

How afoot were marching

With shoulder we were pushing,

And how we were on time ahead of all. |

От ветров и стужи

(От ветров и водки)

Петь мы стали хуже,

(Хрипли наши глотки,)

Но мы скажем тем, кто упрекнет:

– С наше покочуйте,

С наше поночуйте,

С наше повоюйте хоть бы год. | From the winds and the frost

(From the winds and vodka)

Started singing we worse,

(Our throats became hoarse,)

But we shall say to those who blame us:

– Roam as much as we did,

Overnight as we did,

Fight as much as we did just a year. |

Там, где мы бывали,

Нам танков не давали,

Но мы не терялись никогда.

(Репортер погибнет – не беда.)

Но на “эмке” драной

И с одним наганом

Мы первыми въезжали в города. | There, where we have been,

Tanks we never did get,

But we never ever lost our heart.

(A reporter would be killed – so what.)

On an “M’ka” tattered

And with one revolver

We were those who enter cities first. |

(Помянуть нам впору

Мертвых репортеров.

Стал могилой Киев им и Крым.

Хоть они порою

Были и герои,

Не поставят памятника им.) | (We need now remember

Also dead reporters.

Kiev and Crimea are their grave.

Although they were sometimes

They were sometimes heroes,

One won’t put a monument up to them.) |

Так выпьем за победу,

За свою газету,

А не доживем, мой дорогой,

Кто-нибудь услышит,

Снимет и напишет,

Кто-нибудь помянет нас с тобой. | So, let’s drink to the victory,

And to our newspaper,

And if we don’t live to see, my dear,

Somebody then will hear,

Will then film and will write,

Someone will remember us with you! |

![Photos of the similar scenes credited to Khomzor (left) and to Ustinov (right) differ by slight changes of the shooting angle. Were they working simultaneously or perhaps they shared photos for publications?]() Photos of the similar scenes credited to Khomzor (left) and to Ustinov (right) differ by slight changes of the shooting angle. Were they working simultaneously or perhaps they shared photos for publications?

Photos of the similar scenes credited to Khomzor (left) and to Ustinov (right) differ by slight changes of the shooting angle. Were they working simultaneously or perhaps they shared photos for publications?In short, the ‘two soldiers’ photo is almost certainly not taken by

Khaldei. But it well may be that he took another photo of ‘two soldiers, one American and one Russian from Azerbaijan’ in Berlin.

The “Spiegel” article, the “Soviet Capa” refers to, mentions an exhibition “Yevgeny Khaldei – The Decisive Moment. A Retrospective” shown at the

Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin from 9 May to 28 July 2008. An old

blog post by one of the visitors of this exhibition mentions this photo caption, but unfortunately the image links are broken, so we cannot check it visually.

Our hope is that knowledgeable readers may help with additional information in finding answers to the questions that still remain open.

I could stop my story right here, but while reading through the articles and books about the historical meeting at the Elbe, I came across a story I never heard before.

Oath of the Elbe

The historical link up was widely known to citizens of the USSR and “Встреча на Эльбе” i.e. “Meeting at the Elbe” was a catch-phrase in a popular Soviet culture. But I doubt that many heard about the Oath of the Elbe and a small group of veterans, who have been faithful to the memory of their first meeting during the Cold War years of distrust.

The above mentioned book,

Meeting on Elbe collected mostly first hand, sometimes slightly conflicting accounts of the link up on 25 April 1945.

Kotzebue gives dramatic details of their first encounter at the Elbe. They saw people wandering among the debris of destroyed column of cars on the other side of the river, next to the blown up pantone bridge. Judging by their decorations shining in sunlight,

Kotzebue guessed that these are Soviets. On his command Private

Ed Ruff fired two green rockets as an agreed identification signal. Their Polish guide, who joined them in Leckwitz, shouted “Americans”. ‘Russians’ got closer and shouted back calling them to the other side. This meant a lot for ordinary soldiers – the soldiers in front of you are not your enemies anymore – the war is over.

But six joyful Americans and their Polish guide witnessed a dreadful scene at the East side: to reach the coming down Soviets they had to get through heaps of charred bodies of German refugees, apparently killed when the bridge was destroyed. “Suddenly I realized that among all the rejoicing we were standing in the midst of a sea of corpses” remembers Private

Joe Polowsky, who was among the Americans. Most of the killed were civilians – elderly, women and children.

Polowsky recalls that

Kotezbue asked him to translate “Let this day be the day of remembrance of innocent victims”. This is how they took the Oath of Elbe – a promise to do everything to not let this happen again. And quite symbolically the allies were communicating with each other in the language of their enemy – in German.

The dreadful scene of killed refugees in the background could be the reason why photos taken at this first meeting by the present photo-reporter, apparently

Khomzor, are not public. Another reason may be the fact that

Kotzebue later continued his careers in the US Army. He fought in

Korean and

Vietnam proxy wars with the Soviets, retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1967.

It seems that none of the photos in the Soviet newspapers are taken on 25 April, rather on 26-27 April, when official meetings between the allies continued. There were also many unofficial meetings – soldiers of two countries with hostile ideologies were spontaneously meeting and fraternizing for several days.

![American Lieutenant Dwight Brooks (center, in helmet) smiles as he and other members of the 69th Infantry Division pose with Soviet officers from the 58th Guards Division in the German town of Torgau, Germany, late April, 1945. Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Source: waralbum.ru]() American Lieutenant Dwight Brooks (center, in helmet) smiles as he and other members of the 69th Infantry Division pose with Soviet officers from the 58th Guards Division in the German town of Torgau, Germany, late April, 1945. Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Source: waralbum.ru.

American Lieutenant Dwight Brooks (center, in helmet) smiles as he and other members of the 69th Infantry Division pose with Soviet officers from the 58th Guards Division in the German town of Torgau, Germany, late April, 1945. Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Source: waralbum.ru.![The same group of Americans with Major Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’ i.e. deputy commander for political affairs of Silvashko’s 175th Guards Rifle Regiment. Source: waralbum.ru]() The same group of Americans with Major Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’ i.e. deputy commander for political affairs of Silvashko’s 175th Guards Rifle Regiment. Source: waralbum.ru

The same group of Americans with Major Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’ i.e. deputy commander for political affairs of Silvashko’s 175th Guards Rifle Regiment. Source: waralbum.ru![Again, the same group of Americans with possibly Captain Vasiliy Neda , commander of Silvashko’s battalion. Source: waralbum.ru]() Again, the same group of Americans with possibly Captain Vasiliy Neda, commander of Silvashko’s battalion. Source: waralbum.ru.

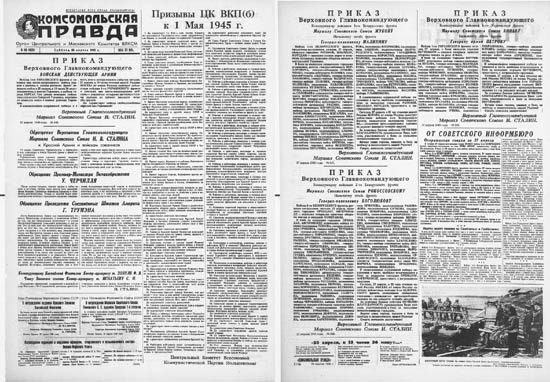

Again, the same group of Americans with possibly Captain Vasiliy Neda, commander of Silvashko’s battalion. Source: waralbum.ru.The front page of the

Komsomolskaya Pravda from 28 April, shown above, features official letters of congratulations from the leaders of the three allied nations – from

Stalin,

Churchill and

Truman. Before this, goes the order of the supreme commander-in-chief

Stalin to fire a salute of 24 salvoes from 324 cannons on 27 April 1945 as a tribute to the participants of the historical event – 1

st Ukrainian Front and Anglo-American troops.

But in fact, both

Kotzebue and

Robertson’s patrols met Soviet troops despite the order not to leave a 5-mile zone from their positions at the Mulde River. What saved them from a tribunal is that the commander of the 1

st American Army

General Hodges was very positive when heard the news and congratulated his generals. Both Major

Larionov and Captain

Neda, who together with Liutenant

Silvashko and Sergeant

Andreyev accompanied

Robertson’s patrol to the headquarters of the 273

rd Infantry Regiment late on 25 April, were soon after expelled from the Communist party and the Soviet army. Many participants of the link up recalled that after few days the troops that made contact with Americans were send back.

The members of

Kotzebue’s patrol including

Shiver appear on many photos in

Ustinov’s album. It is easy to distinguish Americans – they all have got steel helmets. Soviets have not; instead they have got all their decorations on. Interestingly, the Soviet troops on the potential contact line received a special order to have a neat outfit, on meeting Americans to act friendly, but reservedly.

Judging by numbering, these photos apparently are taken on 26 April at the East bank of the Elbe, sometime around the official meeting between the commander of the American 69

th Infantry Division Major General

Emil F. Reinhardt and the commander of the Soviet 58

th Guards Division Major General

Vladimir Vasilyevich Rusakov. By the way, documents show that later in May

Rusakovwas awarded the highest decoration of the Soviet Union,

Order of Lenin. But the only fact I could find about his subsequent fate is that he passed away in 1951 at the age of 42.

So the scene at the ferry-boat crossing is probably a ‘reenactment’ of the meeting, which happened on 25 April, an hour after the initial meeting at the pontoon bridge.

![Americans on the raft (from left to right) are Bob Haag, Ed Ruff, Carl Robinson and Byron Shiver. This photo appeared in the “Komsomolskaya Pravda” issue shown above.]() Americans on the raft (from left to right) are Bob Haag, Ed Ruff, Carl Robinson and Byron Shiver. This photo appeared in the Komsomolskaya Pravda issue shown above.

Americans on the raft (from left to right) are Bob Haag, Ed Ruff, Carl Robinson and Byron Shiver. This photo appeared in the Komsomolskaya Pravda issue shown above.![]()

![Nurse Lyubov Kozinchenko gives flowers to paramedic Carl Robinson. Leftmost is the commander of the 6th Rifle Company Lieutenant Goloborodko, rightmost is the chief of the division artillery headquarters Major Anatoliy Ivanov and next to him is the commander of the 175th Guards Rifle Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr Gordeyev.]() Nurse Lyubov Kozinchenko gives flowers to paramedic Carl Robinson. Leftmost is the commander of the 6th Rifle Company Lieutenant Goloborodko, rightmost is the chief of the division artillery headquarters Major Anatoliy Ivanov and next to him is the commander of the 175th Guards Rifle Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr Gordeyev.

Nurse Lyubov Kozinchenko gives flowers to paramedic Carl Robinson. Leftmost is the commander of the 6th Rifle Company Lieutenant Goloborodko, rightmost is the chief of the division artillery headquarters Major Anatoliy Ivanov and next to him is the commander of the 175th Guards Rifle Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr Gordeyev.![1945.04-1683-0_11bb8_486cca21_orig]()

![1945.04-1684-0_11bbc_4e91f931_orig]()

The photo above shows also one of our heroes –

„Numladze”– the rightmost standing, he looks exactly as on the ‘two soldiers’ photo. But the hero of the story about the Oath of Elbe is the American standing on jeep – Private

Polowsky, native of Chicago.

The outburst of positive friendly rhetoric between the Western powers and Soviets quickly faded away. Few years later Mosfilm film studio was already shooting propaganda movie ‘Encounter at the Elbe’, which portrayed Americans as capitalist occupants of Germany in contrast to humanist Soviet troops. Victorious allies quickly became insidious enemies in the

Cold War for decades.

But it seems that all these years for

Polowsky the hunting image of killed children was a reminder of the Oath of Elbe – the promise to not let this happen again. Back at home he started a small American Veterans of Elbe Meeting / Veterans for Peace organization, keeping in touch with fellow veterans including some of the ‘Russians’ he met at the end of the war.

Polowsky was sending petitions and open letters to world leaders, urging them to stop spreading of nuclear weapons and was campaigning for recognition of the Elbe Day as the day of peace and remembrance of all innocent victims of war. It seems that he succeeded in making his voice heard as the

minutes of the UN General Assembly 197th Plenary Meeting, dated 25 April 1949, include the following statement by the President of the General Assembly:

The PRESIDENT announced that the following draft resolution had been presented by the delegations of Lebanon, the Philippines and Costa Rica:

“The General Assembly,

Recalling that on 25 April 1945 the representatives of fifty nations met together at San Francisco to establish the United Nations in a spirit of understanding and dedication to peace;

Recalling that on 25 April 1945 the soldiers of the Allied armies of the East and of the West joined together at the River Elbe in a spirit of common victory and devotion to peace;

Recommends that on 25 April and each year thereafter on this date the States Members of the United Nations commemorate with appropriate ceremonies the anniversary of that significant day in world history.”

The Assembly would not be able to examine that draft resolution during its third session, but the President had felt that he should inform the delegations of the matter.

A small footnote to this note reads “No official document issued.” It is evident from the rest of the minutes that the General Assembly was captured rather by political ‘exchange of fire’ between the West and the Soviets. Later that year Germany was divided, as the western occupation zones were merged under the Federal Republic of Germany on 23 May and the Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic on 7 October. A year later, in 1950 a

war broke out in divided Korea, brining the USSR and the US to an indirect military confrontation.

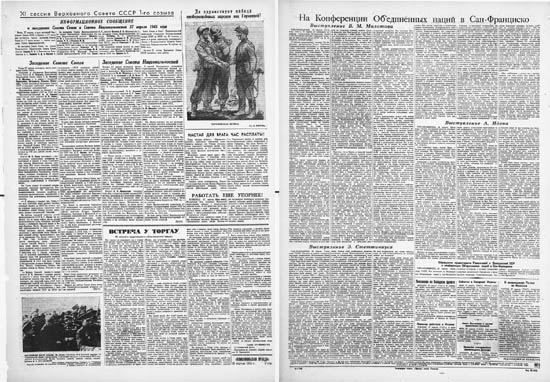

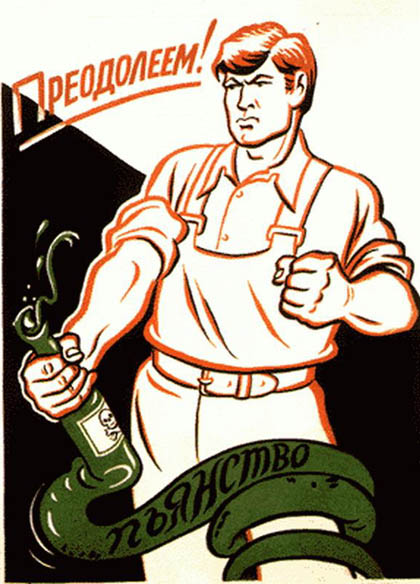

Soviet posters from 1945 “…Red Army together with the armies of our allies will break the backbone of the fascist beast (I. Stalin)” (left) and 1947 “Don’t Fool Around!” (right).

Source: Yandex photo album by user Unter Sergeant. In the heat of anti-soviet propaganda

Polowsky continued sending his

open letters calling to “Renew the Oath at the Elbe”. He reportedly wrote down the formal version of the Oath in 1947, but I could not find its text in the Internet. One could ask if the oath was actually written on paper and signed. Short news from Associated Press, dated 22 April 1950 and entitled

‘Veteran Tears up the Elbe Peace Oath’, suggests that it was. The news quotes

Polowsky’s companion in arms

Ed Ruff saying “It’s not worth the paper it’s written on anymore… Instead of living up to that oath, the Russians have done everything to provoke another war”. It was probably at that time when

Polowsky was prosecuted for ‘un-American activities’.

On the tenth anniversary of the Meeting at the Elbe the Americans sent an invitation to their fellow veterans from the USSR, but the ‘Russian’s declined it, some say because they were asked for fingerprints to get the US visas. Instead an official invitation came from the Soviets to visit Moscow on 9 May 1955 for the Victory Day celebrations. It seems that this was considered as a good occasion for normalizing relations between the two countries.

![Elbe veterans visit Soviet Ambassador. Soviet Ambassador Georgi Zarubin, left, shakes hands with Murray Schulman of Queens Village, N.Y. as a group of U.S. Army veterans who participated in the Elbe River link-up with Russian troops 10 years ago call on him. April 25, 1955 the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Left to right are: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, Soviet second secretary, Elijah Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston and Claude Moore (AP Photo/John Rous). Source: AP Images]() Elbe veterans visit Soviet Ambassador. Soviet Ambassador Georgi Zarubin, left, shakes hands with Murray Schulman of Queens Village, N.Y. as a group of U.S. Army veterans who participated in the Elbe River link-up with Russian troops 10 years ago call on him. April 25, 1955 the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Left to right are: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, Soviet second secretary, Elijah Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston and Claude Moore (AP Photo/John Rous). Source: AP Images.

Elbe veterans visit Soviet Ambassador. Soviet Ambassador Georgi Zarubin, left, shakes hands with Murray Schulman of Queens Village, N.Y. as a group of U.S. Army veterans who participated in the Elbe River link-up with Russian troops 10 years ago call on him. April 25, 1955 the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Left to right are: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, Soviet second secretary, Elijah Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston and Claude Moore (AP Photo/John Rous). Source: AP Images.A group of some ten American veterans, including

Polowsky and

Shiver, got together in New York on 3 May. They have got their visas, but were short on funds for return flights to Paris, where Soviets were planning to meet them and bring to Moscow. To raise the required money

Polowsky appealed to media, but without any response the group decided to break up and go home the next day. A telephone call close to midnight changed the situation – they were invited to a CBS television charity show

“Strike It Rich”.

Polowsky said that “they intended to represent the American point of view and be a credit to President

Eisenhower and the American people”. The viewers from many states called the show to support the veterans. Eventually the sponsor of the show offered to

underwrite $5,580 veterans needed and they started their journey on 6 May.

They arrived in Moscow late in night on 9 May. The following days they met the Soviet veterans, toured places of interest in Moscow, visited a

kolkhoz farm, and had few official banquets in the US Embassy and the

Central House of the Soviet Army. Interestingly, as a decade ago

Ustinov was there with his camera and at the end of the visit he presented each of the veterans an album with photos from 1945 and 1955.

![Shiver shows himself on the photo from 1945. Silvashko is the second from the right.]() Shiver shows himself on the photo from 1945. Silvashko is the second from the right.

Shiver shows himself on the photo from 1945. Silvashko is the second from the right.![The Soviet and American veterans pose in front of the Central House of the Soviet Army.]() The Soviet and American veterans pose in front of the Central House of the Soviet Army.

The Soviet and American veterans pose in front of the Central House of the Soviet Army.Americans take a ride in the Moscow metro. ![1955.05-1723-0_12610_8bbefc3e_orig]() Polowsky (third from right) and Golobordko (first from left) toast at a banquet. The rightmost is probably Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky.

Polowsky (third from right) and Golobordko (first from left) toast at a banquet. The rightmost is probably Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky.Three years later, in 1958, five Soviet veterans, led by writer

Boris Polevoy (1908-1981), who was a frontline reporter of ‘Pravda’ during the war, were on a reciprocal visit in the US, touring New York and Washington.

Polowsky and his friends had to borrow money for entertaining their guests. Without official support from the US government this visit went unnoticed for public. With one exception: The Soviet veterans were invited to a baseball match at the

Griffith Stadium between the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees. When the commentator announced that there are World War Two veterans in the stadium, more than 10,000 spectators applauded as the guests were brought to home plate to meet slugger

Mickey Mantle.

Another reciprocal visit followed next year, and there were few reunions in 1970s.

For a decade, every 25 April, loyal to his oath, a Chicago taxi driver

Joseph Polowsky held a personal vigil to commemorate the Elbe Day. On

Michigan Avenue Bridge he would tell passer-byes the story of friendship at the Elbe River, call for stopping spread of nuclear weapons and for peace in the world.

Polowsky’s last vigil was in 1983, he died of cancer in October that year. Knowing that he is terminally ill

Polowsky made all arrangements for his last will – to be buried at the Elbe River in Torgau, East Germany. All permissions were granted and

Polowsky’s funeral once again brought together Yanks and Reds at the Elbe in November 1983.

Visiting

Polowsky’s grave became an important part of the annual Elbe Day celebrations in Torgau. He became a symbol of loyalty to the Oath of the Elbe, to the spirit of friendship. An American activist and songwriter

Fred Small dedicated the song ‘At the Elbe’ from his 1988 album ‘I Will Stand Fast’ to

Polowsky. I also came across an award-winning 1986 documentary

‘Joe Polowsky – An American Dreamer’ by West German director

Wolfgang Pfeiffer. Unfortunately, I could not watch the film online, but the film still used for information page the image of two soldiers, my story started with.

![]()

On the photo above

Sylvashko pays tribute to the memory of his companion in arms. Probably the last Soviet survivor of those historical events, he passed away in 2010, at the age of 87. The American, shaking hands with

Sylvashko on the famous photo –

Robertson passed away back in 1999. All people, who took the Oath of the Elbe 69 years ago are no more. But the Cold War is still raging over the planet, spreading around the hot zones of many regional conflicts.

Other interesting links

“Встреча на Эльбе” (Encounter at the Elbe) – the 1949 Soviet

propaganda movie in Russian that depicts the link up at the Elbe and subsequent division of Germany to occupation zones:

https://video.yandex.ru/users/cuvschinov-a/view/2478/A 1980s interview with

Joe Polowsky by American prize-winning author and radio personality

Studs Terkel:

http://studsterkel.org/results.php?summary=PolowskyPart 1 and

Part 2.

“Встреча на Эльбе” (Meeting at the Elbe) – this 1990 documentary in Russian features the 45

th anniversary celebrations of the link up in Germany:

http://net-film.ru/film-20264/“Алтарь Победы: Встреча на Эльбе” (The Altar of the Victory: Meeting at the Elbe) – this 2009 documentary in Russian from NTV series interestingly follows the criticism line of the movie released 60 years ago:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DB4Rj3EoIhI“Встречи” (Meetings) – this 2011 documentary in Russian is about

Igor Belousovitch, born in Shanghai son of Russian emigrants, who was part of the

Craig’s patrol:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQDcJG-ms2o

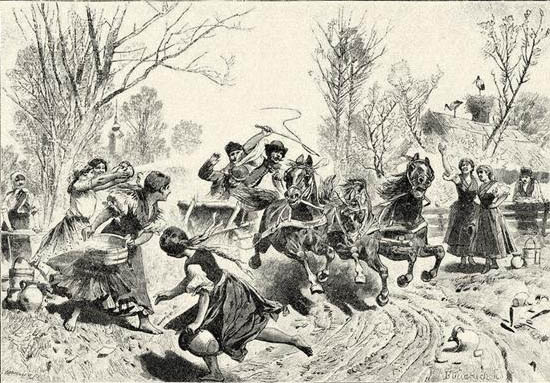

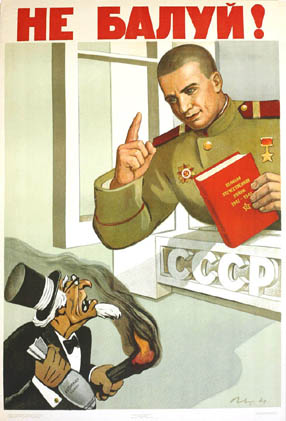

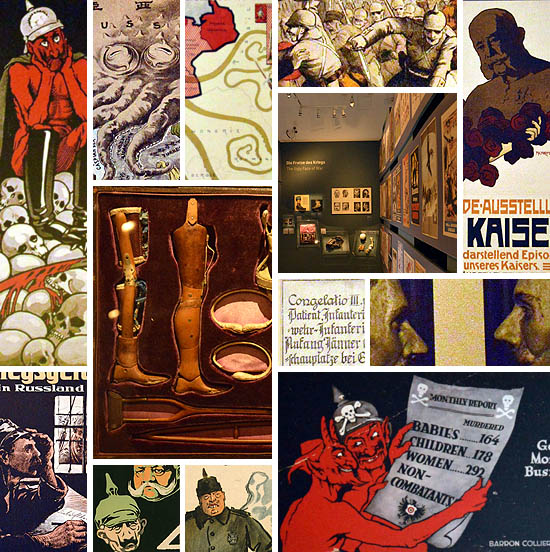

Otto von Kursell: Down with Bolshevism! Bolshevism brings war and destruction, famine and death, 1919

Otto von Kursell: Down with Bolshevism! Bolshevism brings war and destruction, famine and death, 1919 Sergei Igumnov: Let us destroy the spies and diversants, the Trockist-Bukharinist agents of Fascism, 1937.

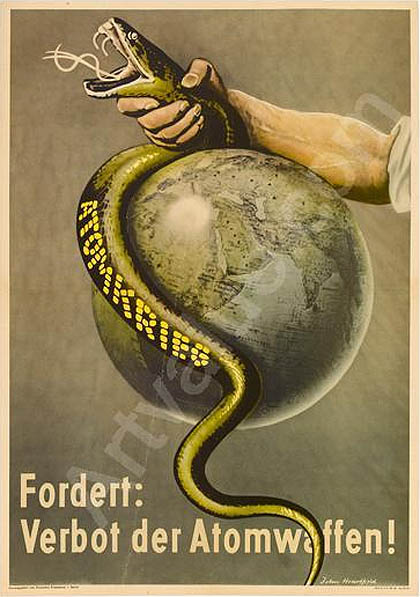

Sergei Igumnov: Let us destroy the spies and diversants, the Trockist-Bukharinist agents of Fascism, 1937. John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld, Bertold Brecht’s playbill designer): We request the ban on nuclear weapons, 1955

John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld, Bertold Brecht’s playbill designer): We request the ban on nuclear weapons, 1955

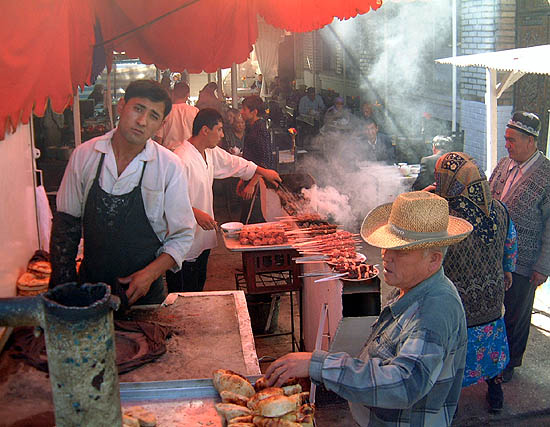

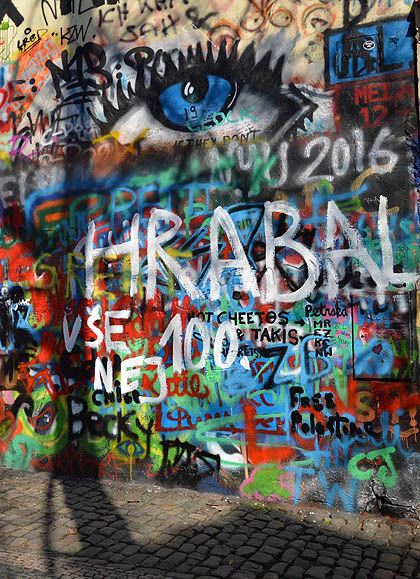

Prague, Malá Strana, this morning

Prague, Malá Strana, this morning

Praga, Malá Strana, esta mañana temprano

Praga, Malá Strana, esta mañana temprano

Already the owl staring down at the street in daylight in the doorway of the Platýz is striking enough, but three houses away, at Národní třída 37 it becomes undeniable: the doorways of Prague have been invaded by birds assimilating themselves to the urban way of life.

Already the owl staring down at the street in daylight in the doorway of the Platýz is striking enough, but three houses away, at Národní třída 37 it becomes undeniable: the doorways of Prague have been invaded by birds assimilating themselves to the urban way of life.

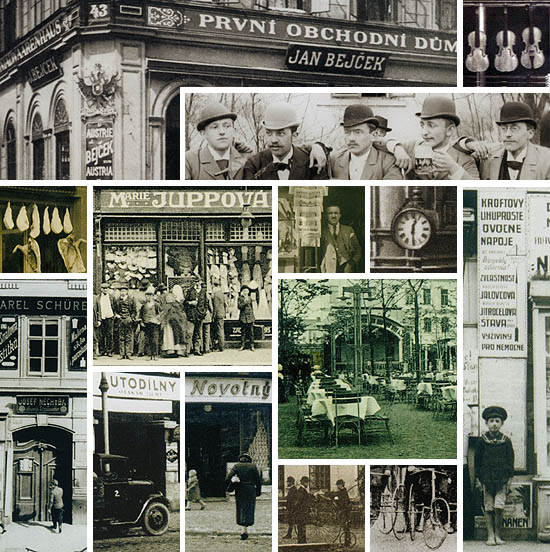

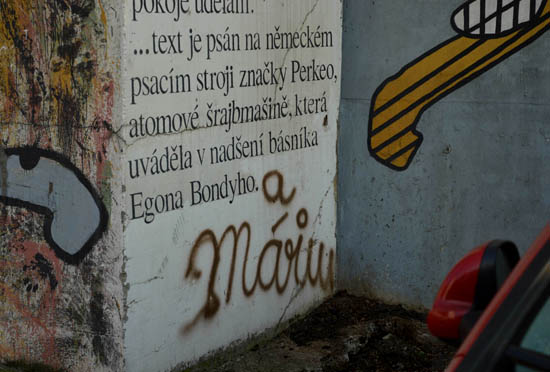

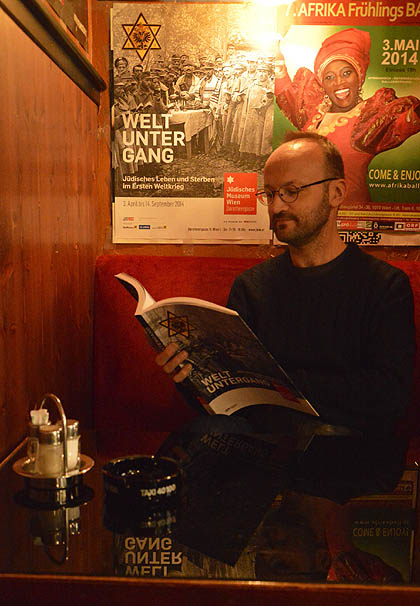

Ce n’est pas une photo de l’album, mais une de celle que je tire de la boîte. Une photo avec un timbre et une lettre au dos.

Ce n’est pas une photo de l’album, mais une de celle que je tire de la boîte. Une photo avec un timbre et une lettre au dos.

Not a photo from the album but one of those I found in the box. A photo with a stamp on it, and a letter on the reverse.

Not a photo from the album but one of those I found in the box. A photo with a stamp on it, and a letter on the reverse.