![]()

Hace casi un año anoté unas

vagas disculpas sobre por qué no escribo más. Dije entonces que con demasiada frecuencia, mientras recojo materiales para la siguiente historia, me asaltan de improviso historias paralelas. Y siguiendo cada nuevo hilo surge más información, y más imágenes y documentos que conducen a nuevas pesquisas. Al final me pasa como a

Aquiles en la

paradoja de

Zenón, nunca llego al final del viaje. Pues bien, he aquí una de esas historias laterales, surgida de la contemplación de una foto de guerra encontrada cuando quería contar la historia de unas cartas de soldados enviadas en 1941 y que nunca llegaron a casa

¿Quién sale en la foto?

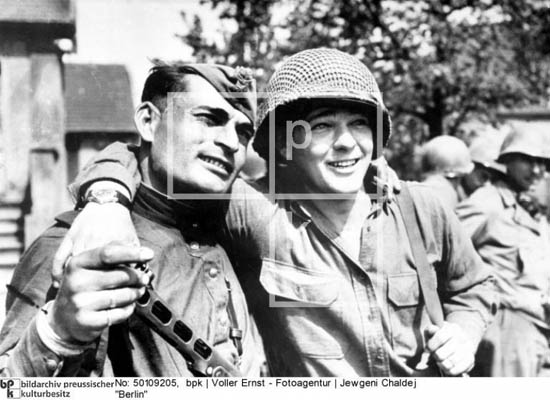

Encontré la foto hará unos dos años, en un archivo fotográfico alemán, buscando simplemente por «Aserbaidschan», es decir, «Azerbaiyán». La foto es del autor de muchas otras que se han convertido en iconos de la Segunda Guerra Mundial:

Yevgueni Jaldéi(1917-1997). Cuenta con un breve título: «Berlín». La fecha apuntada es julio de 1945: el momento en que se permitió a las tropas estadounidenses, británicas y francesas entrar en algunos sectores convenidos de Berlín ocupados por el ejército soviético.

Observando con atención los uniformes se hace evidente que la imagen está en espejo respecto de la original. La descripción dice: «Zwei Soldaten, ein amerikanischer und ein russischer aus Aserbaidschan» (Dos soldados, uno estadounidense y otro ruso de Azerbaiyán). No se revelan sus nombres, por lo que es difícil saber si «ruso» debe entenderse como «soviético».

Pero en Internet encontramos la misma foto con dos pies diferentes que ofrecen los nombres exactos de los soldados.

El soldado soviético se llama

Ivan Numladze, un apellido georgiano. La

base de datos on-line de documentación sobre premios de la Gran Guerra Patriótica y de batallas del ministerio de defensa ruso no da ningún resultado al buscar por este apellido. No debe extrañarnos puesto que esta base de datos aún está incompleta. Sin embargo, en la sección de «pérdidas irrecuperables» del mismo ministerio nuestra búsqueda da con un

Grigoriy Numladze, liberado de su cautiverio en Rumania en octubre de 1944.

La confusión empieza con el nombre del soldado estadounidense, llamado de dos maneras:

Buck Kotzebue y

Byron Shiver. Pero en ambos casos la fecha y el lugar son los mismos: abril de 1945 en algún punto cerca de Torgau, Alemania, donde el Primer Ejército Estadounidense y el Quinto Ejército de Guardias Soviético

se reunieron en el río Elba.

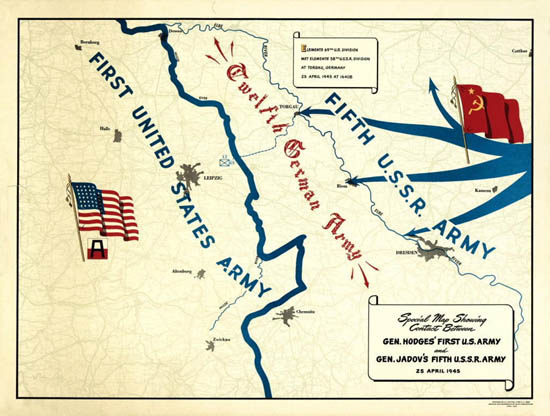

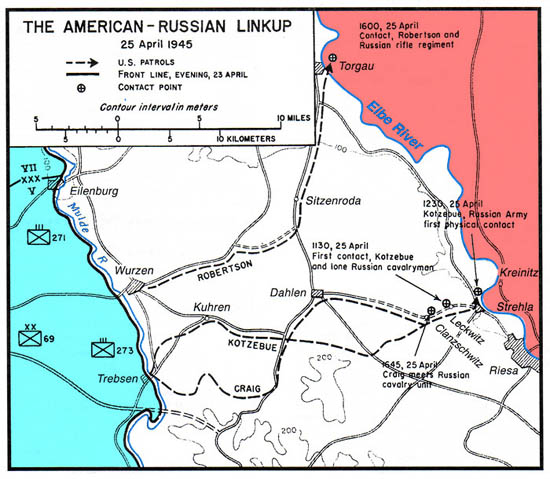

El teniente primero

Albert L. «Buck» Kotzebue, de la Compañía G del 273º Regimiento de Infantería, comandaba una de las tres patrullas estadounidenses que trabaron contacto con las tropas soviéticas el 25 de abril de 1945. Este mapa muestra aproximadamente el lugar y la hora en que la segunda patrulla dirigida por el teniente segundo

William D. Robertson, del mismo regimiento, se encontró con la patrulla soviética encabezada por el teniente

Alexander Silvashko (1922-2010), de la 58ª División de Guardias en un puente destrozado sobre el río Elba, en Torgau. Por pura casualidad, en aquel momento preciso esta reunión se convirtió en el encuentro «oficial» para Occidente, y la

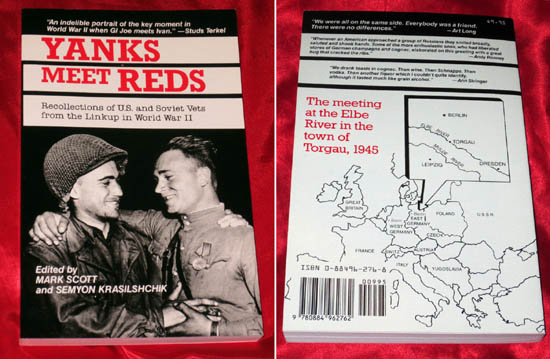

foto de estos dos oficiales tomada por un fotógrafo estadounidense pasó a ser el símbolo de la Alianza del Elba. La misma imagen fue elegida para la portada de un libro publicado simultáneamente en 1988 en EE.UU. y la URSS con diferente título.

Yanks meet Reds, en inglés, y

Встреча на Эльбе (Reunión en el Elba),

en ruso, contiene los recuerdos de los veteranos de ambos lados del Elba. También hubo una tercera patrulla dirigida por el mayor

Fred W. Craig, que fue enviada a averiguar qué había pasado con la patrulla de Kotzebue, que había partido un día antes.

![Cubierta del libro “Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II”. Capra Press, Agosto de 1988. Fuente: ebay.com]() Cubierta del libro Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II, Capra Press, Agosto de 1988. Fuente: ebay.com

Cubierta del libro Yanks meet Reds: recollections of U.S. and Soviet vets from the linkup in World War II, Capra Press, Agosto de 1988. Fuente: ebay.comAsí, una investigación posterior demostró que el primer contacto lo realizó, de hecho, la patrulla de

Kotzebue. En su avance desde Kühren a Strehla, alrededor de las 11:30 se cruzaron con un soldado de caballería «ruso» en el patio de una granja en Leckwitz. Era en realidad un hombre de etnia kazaja, el soldado

Aytkali Alibekov reclutado en 1943 en el

distrito ruso de Tashtagol. La patrulla obtuvo de él algunas direcciones y también el consejo de que tomaran como guía a un prisionero de guerra polaco liberado. El encuentro principal se produjo alguna hora más tarde con la compañía soviética que estaba bajo el mando del teniente

Grigori Goloborodko del 175º Regimiento de Fusileros.

Al parecer no quedaron pruebas fotográficas públicas de esta primera reunión. Pero el artista del Ejército de EE.UU.

Olin Dows (1904-1981), que más tarde fue testigo de la reunión de las fuerzas aliadas, representó el momento en un cuadro añadiendo esta descripción no muy exacta del acontecimiento:

«A las 11:45 de la mañana del 25 de abril de 1945, desde la orilla de Strehla del río Elba, el teniente Kotzebue dispara dos bengalas, una roja y otra verde, con una escopeta como señal de identificación a los rusos que están en la orilla opuesta. Abajo se ve la barca que él con cinco hombres de su patrulla usaron para llegar a la parte rusa. Al fondo está el pontón alemán a la deriva, con las amarras rotas por el fuego de artillería, y el convoy mixto militar y civil alemán que trataba de cruzar el Elba cuando está siendo batido por los tanques rusos».Volviendo a la foto inicial de los soldados, aparentemente el americano representado allí no es

Kotzebue. En primer lugar, porque no es teniente, aparte de que en las otras raras fotos que se han conservado

Kotzebue tiene un aspecto muy diferente, con sus prismáticos, vestido con chaqueta y fumando en pipa.

Así que el joven soldado americano de brillante sonrisa es

Byron Shiver,

natural de Florida, de la misma compañía, que formó parte de la patrulla de Kotzebue. Aparece en algunas otras fotos tomadas durante encuentros posteriores del día después.

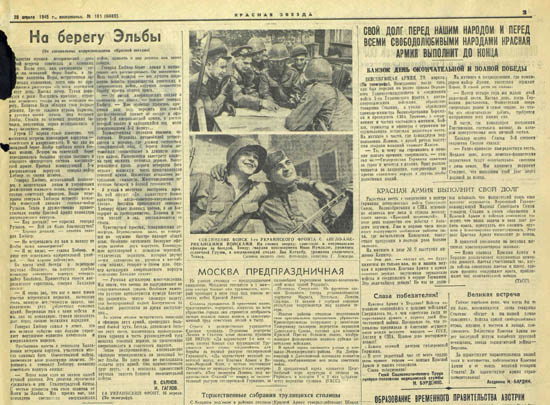

Parece que la causa de esta confusión es el pie de foto aparecido en la edición del 29 de abril de 1945 del periódico oficial del Comisariado del Pueblo para la Defensa de la URSS –

Красная Звезда(Krasnaya Zvezda / Estrella Roja). La foto inferior, en página 3, muestra obviamente la misma escena con ambos soldados desde una perspectiva diferente. La leyenda dice: «EL ENCUENTRO DE LAS TROPAS DEL Ier FRENTE UCRANIANO CON LAS FUERZAS ANGLO-AMERICANAS». Y en la imagen superior: oficiales soviéticos y estadounidenses charlando. Abajo leemos: «El guardia del Ejército Rojo Ivan Numladze, nativo de la soleada Georgia, y el soldado americano

Buck Kotzebue, nativo de la soleada Texas. Fotos de nuestro reportero enviado especial, el capitán

G. Khomzor».

De hecho, el teniente

Kotzebue era oriundo de Houston, Texas. Un dato interesante es que él creía que sus antepasados eran leales súbditos del Imperio Ruso, de origen báltico-germano. Un capitán

Otto von Kotzebue (1787-1846) se hizo famoso por sus exploraciones de Alaska –hay una ciudad y un apellido familiar allí con este nombre. Tal vez, el nombre

Kotzebue fue elegido para este pie de foto después de haber imaginado el cliché de la 'soleada Texas’, y

Numladze bien puede ser un acto de pleitesía al camarada Stalin, «nativo de la soleada Georgia».

Eso no sería extraño –durante largo tiempo la versión oficial soviética atribuyó al sargento georgiano

Meliton Kantaria y al sargento ruso Mikhail Yegorov el mérito de haber izado

la primera bandera soviética sobre el Reichstag. En realidad, otra bandera roja ya había sido izada con bastante antelación en la noche del 30 de abril por un pequeño grupo de voluntarios que incluía al sargento

Mikhail Minin, los sargentos mayores

Gazi Zagitov,

Alexandr Lisimenko y el sargento

Alexei Bobrov. Los documentos dicen que fueron recomendados para la condecoración de

Héroes de la Unión Soviética, pero finalmente obtuvieron la inferior

Orden de la Bandera Roja.

En

Poemas del río Wang ya se habló del

«Capa soviético», acerca de aquella foto icónica de «La bandera de la victoria sobre el Reichstag» de

Jaldéi. Por mucho tiempo se ignoró que la foto en realidad es una

escenificación y que la gente que aparece son el soldado

Alexei Kovalyov de Ucrania y el sargento

Abdulhakim Ismailov de Daguestán. Ahora se sabe que la foto fue retocada para eliminar un «segundo reloj» de la muñeca derecha de Ismailov, ya que esto podría haber provocado preguntas acerca de los saqueos. Por cierto, parece que el soldado soviético de la foto de los «dos soldados» lleva dos anillos en su mano izquierda.

En definitiva, la pregunta seguía abierta: ¿es '

Numladze nativo de la soleada Georgia’ o ‘un soldado de Azerbaiyán'? Así que el 4 de febrero de 2014 finalmente pensé ¿por qué no enviar un

correo electrónico y preguntar a la agencia de fotografía?

Estimado Señor / Señora

Ante todo me gustaría darle las gracias por su noble labor de almacenamiento de imágenes históricas y su puesta a disposición pública por medio de sus servicios online. Mi solicitud se refiere a una famosa foto de 1945 que también obra en sus archivos:

El título en alemán dice: «Dos soldados, uno estadounidense y otro ruso de Azerbaiyán». Fotógrafo: Jewgeni Chaldej / Zwei Soldaten, ein und ein Amerikanischer russischer aus Aserbaidschan. / Aufnahmedatum : Juli 1945 / Aufnahmeort : Berlin / Inventar -Nr:. 1191. Me pregunto si en su equipo podrían aclararme cuál fue el origen de esta leyenda.

La razón de esta solicitud es que otras fuentes dan epígrafes distintos. Por ejemplo, http://victory.rusarchives.ru/index.php?p=31&photo_id=389 dice: «El soldado del Ejército estadounidense Buck L. Kotzebue y el soldado del Ejército Rojo Ivan Numladze en el momento del encuentro en el Elba. - Солдат американской армии Бак Л. Кацебу и красноармеец Иван Нумладзе в момент встречи на Эльбе». De hecho, este título es inexacto, al menos en lo que respecta al soldado estadounidense, ya que se trata del soldado Byron Shiver del 273º regimiento de infantería del Ejército de EE.UU.

Cualquier información adicional sobre este asunto será muy apreciada. Espero con interés tener pronto noticias suyas.

Muchas gracias, Araz

Recibí una breve respuesta al día siguiente:

Muy señor mío:

Gracias por su mensaje. bpk distribuye las imágenes digitales de Chaldej en nombre de la agencia Voller Ernst: http://ernstvolland.de/en

Supongo que el texto es la leyenda original del fotógrafo. No tenemos más información sobre los soldados retratados.

Saludos cordiales, Jan Böttger

Un hombre con una cámara

Ulteriores pesquisas revelaron que mi pregunta podría no ser la correcta. Parece que los contactos iniciados por la patrulla de Robertson eran cubiertos únicamente por fotorreporteros estadounidenses, mientras que los fotógrafos soviéticos registraban principalmente los encuentros en el lado este. ¿Quiénes eran estos fotorreporteros, estaba

Jaldéi entre ellos?

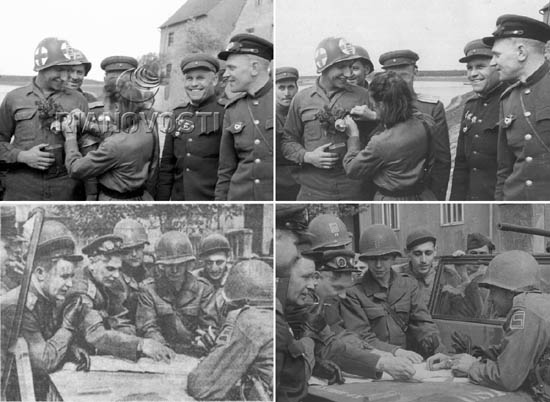

![A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA Novosti]() A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA Novosti

A Soviet and an American soldier at one of the streets of Torgau. Source: RIA NovostiUno era, obviamente, el fotógrafo enviado especial del

Krasnaya Zvezda, capitán

Georgiy Khomzor (1914-1990 ). La foto de «los dos soldados» fue, muy probablemente, tomada por él ya que otra foto muy similar anterior también se le atribuye. Es extraño, sin embargo, que la foto de

Khomzor publicada en

Krasnaya Zvezda con la leyenda que menciona a

Kotzebue y a

Numladze fuera tomada desde un ángulo totalmente diferente.

En realidad su apellido es

Khomutov, pero durante su primera carrera como retocador firmaba sus obras como «Хом. 30 р.», que significa «Khom(utov). (Precio: )30 r(ublos)». Cosa parecida a «ХомЗОр», es decir, «Khomzor», así que el pseudónimo se le quedó puesto. Esta fotoreportero de guerra ganó rápidamente gran popularidad durante el conflicto. El editor ejecutivo de

Krasnaya Zvezda,

David Ortenberg,

recuerda que cuando en mayo de 1945 fue recomendado para ser condecorado con la

Orden de la Guerra Patriótica de segunda clase, el comandante del Primer Frente Ucraniano, mariscal

Ivan Konev (1897-1973 ),

corrigió la lista y lo ascendió al rango superior de la Orden de la Bandera Roja. La sección titulada «breve y concreta descripción de los hechos de armas o méritos personales» del impreso para la condecoración menciona que «En el río Elba fotografió la reunión histórica de las tropas del 1er Frente Ucraniano con el Ejército Estadounidense».

![A rare photo showing Lieutenant Kotzebue smoking his pipe by Khomzor. Source: RIA Novosti]() Una rara foto de Khomzor que muestra al teniente Kotzebue fumando su pipa. Fuente: RIA Novosti

Una rara foto de Khomzor que muestra al teniente Kotzebue fumando su pipa. Fuente: RIA NovostiA pesar de esto, hoy no hay ni siquiera una página de Wikipedia dedicada a él, o una foto suya en Internet que nos ayude a averiguar si el hombre con la cámara de la foto inferior es

Khomzor. A juzgar por su atuendo no lo es, tampoco está claro si es capitán o teniente. Las insignias del uniforme más bien lo identificarían con el capitán

Alexandr Ustinov (1909-1995), fotorreportero del

diario Pravda, que para julio de 1944 ya había sido galardonado con la

Medalla «Por el valor» y la

Orden de la Estrella Roja. Pero a diferencia de este hombre Ustinov tenía una espléndida cabellera y su medalla debería ser de la antigua versión de 1939-1943, con

montura pequeña.

![A photo of the same scene, taken by American Private Igor Belousovitch who was in Major Craig’s patrol (Craig is the leftmost American – they all put helmets on), shows most probably Ustinov working. Source: The Moscow Times]() Una foto de la misma escena, tomada por el soldado americano Igor Belousovitch, miembro de la patrulla del mayor Craig (Craig es el americano más a la izquierda – todos con el casco puesto) nos muestra muy probablemente a Ustinov trabajando. Fuente: The Moscow Times.

Una foto de la misma escena, tomada por el soldado americano Igor Belousovitch, miembro de la patrulla del mayor Craig (Craig es el americano más a la izquierda – todos con el casco puesto) nos muestra muy probablemente a Ustinov trabajando. Fuente: The Moscow Times.Esta foto estaba en el álbum que Ustinov presentó a los veteranos incluyendo a

Silvashko, que después de la guerra fue director de una escuela de pueblo y profesor de historia en el distrito bielorruso de Kletsk. Silvashko más tarde la donó al museo de la ciudad de Kletsk y las imágenes escaneadas apareceron en Internet.

Kotzebue en sus recuerdos menciona que uno de los primeros tres «rusos» con que se encontraron en el río Elba era un fotógrafo con rango de capitán, que tomó las fotos. Debe ser

Khomzor, pues Ust

inov escribe en sus memorias

С «лейкой» и блокнотом (con una Leica y un cuaderno) que llegó al río Elba cruzándolo solo el 26 de abril. También menciona que «Más tarde, un nutrido grupo de periodistas norteamericanos, camarógrafos y colegas míos fotorreporteros llegó hasta nosotros. Entre los periodistas soviéticos estaban

Konstantin Simonov, Sergey Krushinski de Komsomolka y

GeorgiyKhomzor, fotorreportero del

Krasnaya Zvezda». Curiosamente, muchas fuentes, entre ellas la hija de

Ustinov, afirman que Ustinov fue «el único fotógrafo soviético testigo de la reunión en el Elba».

Por cierto, el título del libro «Con una Leica y un cuaderno» está tomado de una popular «Canción de los reporteros de guerra», escrita por

Konstantin Simonov (1915-1979) y musicada por

Matvey Blanter(1903-1990), el autor de la famosa «Katyusha». Simonov lo escribió en 1943 como

«canción de taberna de los Reporteros», y algunas palabras fueron censuradas en la popular versión oficial.

От Москвы до Бреста

Нет такого места,

Где бы ни скитались мы в пыли,

С “лейкой” и с блокнотом,

А то и с пулеметом

Сквозь огонь и стужу мы прошли. | Desde Moscú hasta Brest

no hay lugar donde no hayamos

vagado por el polvo.

Con una «Leica» y un cuaderno,

y a veces con un fusil

atravesamos el fuego y la helada. |

(Жив ты или помер –

Главное, чтоб в номер

Материал успел ты передать.

И чтоб, между прочим,

Был фитиль всем прочим,

А на остальное - наплевать!) | (Vivos o muertos,

lo principal es: para esta entrega

han de llegar a tiempo los materiales.

Por cierto, que sean

la envidia de los otros,

¡y que todo los demás nos importe un comino!) |

Без глотка, товарищ,

(Без ста грамм, товарищ,)

Песню не заваришь,

Так давай за дружеским столом

(Так давай по маленькой хлебнем!)

Выпьем за писавших,

Выпьем за снимавших,

Выпьем за шагавших под огнем. | Sin un ochavo, camarada

(sin media pinta/100 gramos, camarada)

una canción querría cantar

sentados a una amistosa mesa

(¡vamos, traguemos sorbo a sorbo!)

Un trago para los que escriben,

un trago para los que filman

un trago para los que marchan bajo el fuego. |

Есть, чтоб выпить, повод -

За военный провод,

За У-2, за “эмку”, за успех...

Как пешком шагали,

Как плечом толкали,

Как мы поспевали раньше всех. | Para beber tenemos un motivo

para una despedida militar,

para U-2, para el «M’ka», para el éxito…

Con qué marcha avanzábamos

empujando con los hombros

y cómo llegamos puntuales delante de todos. |

От ветров и стужи

(От ветров и водки)

Петь мы стали хуже,

(Хрипли наши глотки,)

Но мы скажем тем, кто упрекнет:

– С наше покочуйте,

С наше поночуйте,

С наше повоюйте хоть бы год. | Con los vientos y la helada

(Con los vientos y el vodka)

nuestro canto empeora,

(nuestras gargantas quedan roncas)

pero diremos a quienes nos culpen:

anda tanto como nosotros,

toda la noche, como nosotros,

pelea tanto como nosotros en un año. |

Там, где мы бывали,

Нам танков не давали,

Но мы не терялись никогда.

(Репортер погибнет – не беда.)

Но на “эмке” драной

И с одним наганом

Мы первыми въезжали в города. | Allí, donde hemos estado,

no hemos vencido a los tanques,

pero nunca perdimos el valor.

(Si muriera un reportero, qué más da).

Con una estropeada M’ka

y con un revólver, éramos

los que entrábamos antes en las ciudades. |

(Помянуть нам впору

Мертвых репортеров.

Стал могилой Киев им и Крым.

Хоть они порою

Были и герои,

Не поставят памятника им.) | (Tenemos que recordar ahora

también a los reporteros caídos.

Kiev y Crimea son sus tumbas.

Aunque a veces fueron,

fueron a veces héroes

no les alzarán un monumento) |

Так выпьем за победу,

За свою газету,

А не доживем, мой дорогой,

Кто-нибудь услышит,

Снимет и напишет,

Кто-нибудь помянет нас с тобой. | ¡Bebamos pues por la victoria,

y por nuestro periódico,

y si no vivimos para verlo, querida,

luego alguien oirá,

alguien después filmará y escribirá,

alguien nos recordará contigo! |

![Photos of the similar scenes credited to Khomzor (left) and to Ustinov (right) differ by slight changes of the shooting angle. Were they working simultaneously or perhaps they shared photos for publications?]() Las fotos de escenas similares atribuidas a Khomzor (izquierda) y a Ustinov (derecha) difieren en pequeños cambios del ángulo de enfoque. ¿Trabajaron simultáneamente o puede que compartieran las fotos para las publicaciones?

Las fotos de escenas similares atribuidas a Khomzor (izquierda) y a Ustinov (derecha) difieren en pequeños cambios del ángulo de enfoque. ¿Trabajaron simultáneamente o puede que compartieran las fotos para las publicaciones?En resumen, la foto de «los dos soldados» casi seguro que no fue tomada por

Jaldéi. Pero bien puede ser que tomara otra foto de «dos soldados, uno estadounidense y otro ruso de Azerbaiyán» en Berlín. El

artículo de Spiegel citado en «El Capa soviético» menciona la exposición «

Yevgueni Jaldéi– El momento decisivo. Una retrospectiva» del

Martin Gropius Bau de Berlín (abierta de 9 de mayo a 28 julio de 2008). Una vieja entrada del

blog de uno de los visitantes de la exposición mencionaba este pie de foto, pero por desgracia los enlaces de la imagen no funcionan, por lo que no podemos hacer nuestra propia comprobación visual.

Nuestra esperanza es que los lectores bien informados nos ayuden con datos adicionales para las preguntas que aún permanecen abiertas.

Podría haber cerrado aquí la historia, pero al leer más artículos y libros sobre la famosa reunión en el Elba, me topé con un relato que no había oído antes.

El Juramento del Elba

El histórico encuentro fue conocido ampliamente por los ciudadanos de la URSS y la expresión «Встреча на Эльбе», es decir, «Reunión en el Elba» se convirtió en un dicho de la cultura popular soviética. Pero dudo que fueran muchos quienes tuvieron noticia del Juramento del Elba y del pequeño grupo de veteranos que continuaron siendo fieles a la memoria de su primer encuentro durante los largos años de desconfianza de la Guerra Fría.

El mencionado libro

Reunión en el Elba, recogió relatos en su mayoría de primera mano, a veces un poco contradictorios, del encuentro del 25 de abril de 1945.

Kotzebue da detalles dramáticos de su primer encuentro en el Elba. Vieron gente deambulando entre los restos de la columna de coches destruida al otro lado del río, junto al pontón que había sido medio volado. Por el brillo de las insignias bajo la luz del sol

Kotzebue supuso que eran soviéticos. A una orden suya, el soldado

Ed Ruff lanzó dos bengalas verdes como señal de identificación acordada. Su guía polaco, que se les había unido en Leckwitz, gritó «americanos». Los «rusos» se acercaron y gritaron a su vez desde la otra orilla. Esto significaba mucho para un soldado corriente: los hombres que estaban delante ellos ya no eran más los enemigos, la guerra había terminado.

Pero los seis alegres americanos y su guía polaco fueron testigos de una escena terrible en el lado este: para llegar a los soviéticos que descendían tuvieron que pasar entre montones de cuerpos carbonizados de refugiados alemanes, al parecer murieron cuando el puente fue destruido. «De repente me di cuenta de que en nuestra alegría nos habíamos parado en medio de un mar de cadáveres», recuerda el soldado americano Joe Polowsky. La mayoría de muertos eran civiles –ancianos, mujeres y niños–.

Polowsky recuerda que

Kotezbue le pidió que tradujera «Que este día sea el día de la memoria de las víctimas inocentes». Esta es la forma que tomó el Juramento del Elba: la promesa de hacer todo lo posible para impedir que algo así volviera a suceder. Y, de manera muy simbólica, los aliados se comunicaban entre ellos en la lengua de su enemigo, el alemán.

La terrible escena de los refugiados muertos en el fondo podría ser la razón por la que las fotos tomadas en esta primera reunión por el fotógrafo de guerra presente, aparentemente

Khomzor, no fueran hechas públicas. Otra razón puede ser que Kotzebue más tarde continuó su carrera en el ejército de EE.UU. Peleó en

Corea y en

Vietnam, guerras, en el fondo, contra los soviéticos, y se retiró como teniente coronel en 1967.

Parece que ninguna de las fotos de los periódicos soviéticos fue tomada el 25 de abril, más bien durante los días 26-27, cuando prosiguieron las reuniones oficiales entre los aliados. Hubo también muchas otras reuniones no oficiales –los soldados de ambos países, de ideologías tan hostiles, se reunían de manera espontánea y confraternizaron durante varios días.

![American Lieutenant Dwight Brooks (center, in helmet) smiles as he and other members of the 69th Infantry Division pose with Soviet officers from the 58th Guards Division in the German town of Torgau, Germany, late April, 1945. Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Source: waralbum.ru]() El teniente americano Dwight Brooks (centro, con casco) sonríe mientras posa, junto con otros miembros de la 69º División de Infantería, con oficiales soviéticos de la 58ª División de Guardias en la ciudad alemana de Torgau, a fines de abril de 1945. Foto de PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Fuente: waralbum.ru.

El teniente americano Dwight Brooks (centro, con casco) sonríe mientras posa, junto con otros miembros de la 69º División de Infantería, con oficiales soviéticos de la 58ª División de Guardias en la ciudad alemana de Torgau, a fines de abril de 1945. Foto de PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Fuente: waralbum.ru.![The same group of Americans with Major Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’ i.e. deputy commander for political affairs of Silvashko’s 175th Guards Rifle Regiment. Source: waralbum.ru]() El mismo grupo de americanos con el mayor Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’, es decir, comandante adjunto para asuntos políticos del 175º Regimiento de Fusileros de la Guardia de Silvashko. Fuente: waralbum.ru

El mismo grupo de americanos con el mayor Anfim Larionov, ‘zampolit’, es decir, comandante adjunto para asuntos políticos del 175º Regimiento de Fusileros de la Guardia de Silvashko. Fuente: waralbum.ru![Again, the same group of Americans with possibly Captain Vasiliy Neda , commander of Silvashko’s battalion. Source: waralbum.ru]() Otra foto del mismo grupo de americanos posiblemente con el capitán Vasily Neda, comandante del batallón de Silvashko. Fuente: waralbum.ru

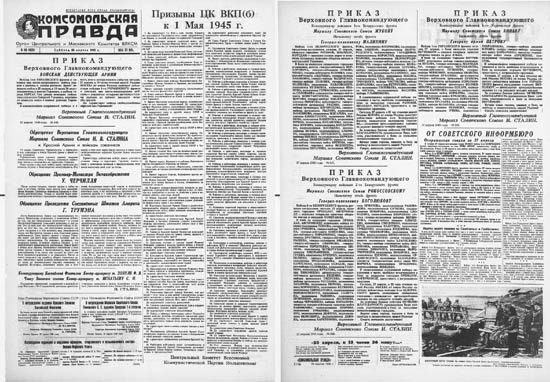

Otra foto del mismo grupo de americanos posiblemente con el capitán Vasily Neda, comandante del batallón de Silvashko. Fuente: waralbum.ruLa portada del

Komsomolskaya Pravda del 28 de abril reproducida arriba muestra cartas oficiales de felicitación de los líderes de las tres naciones aliadas,

Stalin,

Churchill y

Truman. Precediéndolas, va a la orden del comandante en jefe supremo,

Stalin, de disparar un saludo de 24 salvas con 324 cañones el 27 de abril de 1945 como homenaje a los participantes en el histórico evento –el 1er Frente Ucraniano y las Tropas Anglo-Estadounidenses.

Pero, de hecho, tanto la patrulla de

Kotzebue como la de

Robertson se reunieron con las tropas soviéticas a pesar de la orden de no alejarse de un perímetro de 5 millas desde sus posiciones en el río Mulde. Lo que los salvó de verse ante un tribunal es que el comandante del primer ejército americano, el

General Hodges tuvo una actitud muy positiva cuando oyó la noticia y felicitó a sus generales. Tanto el mayor

Larionov como el capitán Neda, que junto con el teniente

Silvashko y el sargento

Andreyev acompañaron a la patrulla de Robertson al acuartelamiento del 273º regimiento de infantería luego el 25 de abril, fueron poco después expulsados del Partido Comunista y del ejército soviético. Muchos participantes del encuentro recordarían que, pasados unos pocos días, las tropas soviéticas que entraron en contacto con los estadounidenses fueron enviadas de vuelta.

Los miembros de la patrulla de

Kotzebue incluido Shiver aparecen en muchas fotos del álbum de

Ustinov. Es fácil distinguir a los estadounidenses, llevan todos cascos de acero, no así los soviéticos. Pero éstos lucen todas sus insignias. Curiosamente, las tropas soviéticas que podían estar en la línea de contacto recibieron la orden especial de tener el equipamiento ordenado y de que al verse con los estadounidenses actuaran amistosamente pero de manera reservada.

A juzgar por la numeración, estas fotos debieron ser tomadas el 26 de abril en la orilla este del río Elba, en algún momento alrededor de la reunión oficial entre el comandante de la 69ª División de Infantería estadounidense, mayor general

Emil F. Reinhardt y el comandante de la 58ª División de Guardias soviética, mayor general

Vladimir Vasilyevich Rusakov. Por cierto, los documentos muestran que a fines de mayo a

Rusakovle otorgaron la más alta condecoración de la Unión Soviética, la

Orden de Lenin. Pero el único dato que pude encontrar acerca de su suerte posterior es que falleció en 1951 a la edad de 42 años.

Así que la escena en el transbordador es probablemente una «recreación» del encuentro, que tuvo lugar el 25 de abril, una hora después de la reunión primera en el pontón de barcazas.

![Americans on the raft (from left to right) are Bob Haag, Ed Ruff, Carl Robinson and Byron Shiver. This photo appeared in the “Komsomolskaya Pravda” issue shown above.]() Los americanos en el transbordador (de izquierda a derecha) son Bob Haag, Ed Ruff,Carl Robinson y Byron Shiver. Esta foto apareció en el número del Komsomolskaya Pravda reproducido arriba.

Los americanos en el transbordador (de izquierda a derecha) son Bob Haag, Ed Ruff,Carl Robinson y Byron Shiver. Esta foto apareció en el número del Komsomolskaya Pravda reproducido arriba.![]()

![Nurse Lyubov Kozinchenko gives flowers to paramedic Carl Robinson. Leftmost is the commander of the 6th Rifle Company Lieutenant Goloborodko, rightmost is the chief of the division artillery headquarters Major Anatoliy Ivanov and next to him is the commander of the 175th Guards Rifle Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr Gordeyev.]() La enfermera Lyubov Kozinchenko da flores al sanitario Carl Robinson. En el extremo izquierdo el comandante de la 6ª Compañía de Fusileros, teniente Goloborodko. A la derecha está el jefe de los cuarteles de la División de Artillería, mayor Anatoly Ivanov y a su lado el comandante del 175º Regimiento de Fusileros, teniente coronel Aleksandr Gordeyev.

La enfermera Lyubov Kozinchenko da flores al sanitario Carl Robinson. En el extremo izquierdo el comandante de la 6ª Compañía de Fusileros, teniente Goloborodko. A la derecha está el jefe de los cuarteles de la División de Artillería, mayor Anatoly Ivanov y a su lado el comandante del 175º Regimiento de Fusileros, teniente coronel Aleksandr Gordeyev.![1945.04-1683-0_11bb8_486cca21_orig]()

![1945.04-1684-0_11bbc_4e91f931_orig]()

La foto de arriba muestra también a uno de nuestros héroes, «

Numladze» –de pie, más a la derecha, con el aspecto exacto de la foto de «los dos soldados». Pero el héroe de la historia sobre el Juramento del Elba es el americano de pie sobre el jeep, el soldado

Polowsky, nativo de Chicago.

La explosión de retórica amistosa y positiva entre las potencias occidentales y los soviéticos se desvaneció rápidamente. A los pocos años el estudio de cine Mosfilm ya estaba rodando la película de propaganda Encuentro en el Elba, que retrataba a los estadounidenses como ocupantes capitalistas de Alemania, en contraste con las humanistas tropas soviéticas. Los aliados victoriosos se convirtieron rápidamente en insidiosos enemigos durante las décadas de la

Guerra Fría.

Pero parece que en todos estos años

Polowsky tenía presente la imagen inquietante de los niños muertos como recordatorio del Juramento del Elba: no dejar que esto vuelva a suceder. De regreso a casa organizó reuniones de la pequeña asociación de Veteranos Americanos del Elba / Veteranos por la Paz, intentando mantenerse en contacto con aquellos compañeros, incluyendo a algunos de los «rusos» que conoció en el final de la guerra.

Polowsky envió peticiones y cartas abiertas a los líderes mundiales instándolos a detener la proliferación de armas nucleares y haciendo una campaña por el reconocimiento del Día del Elba como día de la paz y del recuerdo de todas las víctimas inocentes de la guerra. Parece que tuvo algún éxito en hacer oír su voz, como refleja el

acta de la reunión plenaria de la 197ª Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas de fecha 25 de abril de 1949, donde se incluye la siguiente declaración del Presidente de la Asamblea General:

El PRESIDENTE anunció que el siguiente proyecto de resolución ha sido presentado por las delegaciones de Líbano, Filipinas y Costa Rica:

«La Asamblea General,

Recordando que el 25 de abril de 1945, representantes de cincuenta países se reunieron en San Francisco para crear las Naciones Unidas en un espíritu de mutua comprensión y dedicación a la paz;

Recordando que el 25 de abril 1945, los soldados de los ejércitos aliados de Oriente y de Occidente se unieron en el río Elba en un espíritu de victoria y devoción por la paz común;

Recomienda que el 25 de abril y posteriormente cada año en esta fecha, los Estados Miembros de las Naciones Unidas conmemoren con ceremonias el aniversario de ese día importante en la historia del mundo».

La Asamblea no tuvo ocasión de examinar el proyecto de resolución en su tercera sesión, pero el Presidente afirma que deberá informar a las delegaciones sobre la materia.

Una pequeña nota al pie de estas líneas dice: «No se emitió documento oficial». Es evidente por el resto del acta que la Asamblea General quedó pillada por el ‘fuego cruzado’ político entre Occidente y los soviéticos. Más tarde ese año Alemania fue dividida, ya que las zonas de ocupación occidentales se fusionaron bajo la República Federal de Alemania el 23 de mayo y la zona soviética se convirtió en la República Democrática Alemana el 7 de octubre. Un año más tarde, en 1950, estalló la guerra en la dividida Corea, devolviendo a la URSS y los EE.UU. a una indirecta confrontación militar.

En el calor de la propaganda antisoviética,

Polowsky continuó enviando sus

cartas abiertas que llamaban a «renovar el Juramento del Elba». Según los informes, escribió la versión oficial del juramento en 1947 pero no puedo encontrar su texto en Internet. Podríamos preguntarnos si el juramento fue realmente escrito en un papel y firmado. Una nota breve de la Associated Press de 22 de abril de 1950 titulada

«Los Veteranos deshacen el Juramento de Paz del Elba», sugiere que así fue. La noticia cita al compañero de armas de

Polowsky,

Ed Ruff diciendo: «Ya no vale ni el papel en que está escrito... En lugar de estar a la altura de aquel juramento, los rusos han hecho todo lo posible para provocar otra guerra». Probablemente fue en ese momento cuando Polowsky fue procesado por «actividades antiamericanas».

En el décimo aniversario de la Reunión en el Elba los estadounidenses enviaron una invitación a sus compañeros veteranos de la URSS, pero los «rusos» la declinaron, algunos dicen que debido a que se les solicitaron las huellas dactilares para obtener el visado de entrada en Estados Unidos. En respuesta, llegó una invitación oficial de los soviéticos para visitar Moscú el 9 de mayo de 1955, por las celebraciones del Día de la Victoria. Parece que esto fue considerado como una buena ocasión para normalizar las relaciones entre los dos países.

![Elbe veterans visit Soviet Ambassador. Soviet Ambassador Georgi Zarubin, left, shakes hands with Murray Schulman of Queens Village, N.Y. as a group of U.S. Army veterans who participated in the Elbe River link-up with Russian troops 10 years ago call on him. April 25, 1955 the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Left to right are: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, Soviet second secretary, Elijah Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston and Claude Moore (AP Photo/John Rous). Source: AP Images]() Veteranos del Elba visitan al embajador soviético. El embajador soviético Georgi Zarubin, izquierda, estrecha la mano de Murray Schulman de Queens Village, Nueva York, así como un grupo de veteranos del Ejército de EE.UU. que participaron en el encuentro en el río Elba lo hizo con las tropas rusas hace 10 años. 25 de abril de 1955 en la embajada rusa en Washington D.C. De izquierda a derecha son: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, segundo secretario soviético, Elías Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston y Claude Moore (AP Photo / John Rous). Fuente: AP Images.

Veteranos del Elba visitan al embajador soviético. El embajador soviético Georgi Zarubin, izquierda, estrecha la mano de Murray Schulman de Queens Village, Nueva York, así como un grupo de veteranos del Ejército de EE.UU. que participaron en el encuentro en el río Elba lo hizo con las tropas rusas hace 10 años. 25 de abril de 1955 en la embajada rusa en Washington D.C. De izquierda a derecha son: Edwin Jeary, Robert Haag, Byron Shiver, John Adams, Charles Forrester, Zarubin, William Weisel, Yuri Gouk, segundo secretario soviético, Elías Sams, Schulman, Robert Legal, Fred Johnston y Claude Moore (AP Photo / John Rous). Fuente: AP Images.Un grupo de unos diez veteranos estadounidenses, incluyendo a

Polowsky y

Shiver, se reunieron en Nueva York el 3 de mayo. Habían conseguido sus visados, pero se quedaron cortos en la obtención de fondos para el vuelo de regreso a París, donde los soviéticos tenían previsto reunirse con ellos y llevarlos a Moscú. Para recaudar el dinero necesario, Polowsky hizo un llamamiento a los medios de comunicación, pero no hubo respuesta así que el grupo decidió dar marcha atrás y volver a casa al día siguiente. Una llamada telefónica cerca de la medianoche cambió la situación: estaban invitados a un programa de ayuda del canal de televisión CBS

«Strike it Rich».

Polowsky dijo que «tenían la intención de ser representantes del punto de vista estadounidense y dar un buena imagen del presidente Eisenhower y el pueblo americano». Espectadores de muchos estados llamaron al espectáculo televisivo para apoyar a los veteranos. Finalmente, el patrocinador del programa proporcionó

los 5.580 $ necesarios y los veteranos emprendieron viaje el 6 de mayo.

Llegaron a Moscú bien entrada la noche del 9 de mayo. Los siguientes días se reunieron con los veteranos soviéticos, recorrieron lugares de interés en Moscú, visitaron una granja de koljós, y asistieron a algunos banquetes oficiales en la Embajada de los EE.UU. y la

Casa Central del Ejército Soviético. Curiosamente, como había ocurrido una década atrás, Ustinov estaba allí con su cámara y al final de la visita regaló a cada uno de los veteranos un álbum con las fotos de 1945 y 1955.

![Shiver shows himself on the photo from 1945. Silvashko is the second from the right.]() Shiver señala su propio retrato en la foto de 1945. Silvashko es el segundo por la derecha.

Shiver señala su propio retrato en la foto de 1945. Silvashko es el segundo por la derecha.![The Soviet and American veterans pose in front of the Central House of the Soviet Army.]() Los veteranos soviéticos y americanos posan delante de la Casa Central del Ejército Soviético.

Los veteranos soviéticos y americanos posan delante de la Casa Central del Ejército Soviético.Los americanos dan una vuelta en el metro de Moscú. ![1955.05-1723-0_12610_8bbefc3e_orig]() Polowsky (tercero por la derecha) brinda en un banquete. En el extremo izquierdo vemos probablemente al delegado del Ministro de Defensa de la URSS, mariscal Vasily Sokolovsky.

Polowsky (tercero por la derecha) brinda en un banquete. En el extremo izquierdo vemos probablemente al delegado del Ministro de Defensa de la URSS, mariscal Vasily Sokolovsky.Tres años después, en 1958, cinco veteranos soviéticos liderados por el escritor

Boris Polevoy (1908-1981), reportero de primera línea de fuego de Pravda durante la guerra, devolvieron la visita recorriendo Nueva York y Washington. Polowsky y sus amigos tuvieron que pedir dinero prestado para agasajar a los invitados. Sin ningún apoyo oficial del gobierno de EE.UU. la visita pasó desapercibida para el público. Con una excepción: los veteranos soviéticos fueron invitados a un partido de béisbol en el

Estadio Griffith donde se enfrentaban los Senadores de Washington y los Yanquis de Nueva York. Cuando el comentarista anunció que había unos veteranos de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en el estadio, más de 10.000 espectadores aplaudieron mientras ellos eran conducidos hasta el home plate de la cancha para saludar al bateador

Mickey Mantle.Otra visita tuvo lugar al año siguiente, y unas pocas más durante los años 70.

A lo largo de una década, cada 25 de abril, fiel a su juramento, el taxista de Chicago

Joseph Polowsky celebraba su vigilia personal para conmemorar el Día del Elba. En el

puente de Michigan Avenue contaba a los transeúntes la historia de la amistad del río Elba, hablaba de la necesidad de detener la propagación de armas nucleares y hacía votos por la paz mundial. La última vigilia de

Polowsky fue en 1983, murió de cáncer en octubre de ese año. Sabiendo que su enfermedad era terminal, lo arregló todo para que se cumpliera su última voluntad: ser enterrado a orillas del río Elba, en Torgau, Alemania del Este. Se le concedieron los permisos oportunos y el funeral de

Polowsky reunió de nuevo a Yanquis y Rojos en el Elba. Era el mes de noviembre de 1983.

Desde entonces, visitar la tumba de

Polowsky es una parte importante de las celebraciones anuales del Día del Elba en Torgau.

Polowsky se ha convertido en el símbolo de lealtad al Juramento del Elba, al espíritu de la amistad. El activista y compositor estadounidense

Fred Smallle dedicó la canción 'At the Elbe' de su álbum de 1988 'I Will Stand Fast’. También hay un documental premiado de 1986

'Joe Polowsky - An American Dreamer', del director alemán occidental

Wolfgang Pfeiffer. Por desgracia, no he podido ver la película on-line, pero aún aparece la imagen de «los dos soldados» en la página de información sobre el film, con ella empezó mi historia.

![]()

En la foto de arriba

Sylvashko rinde homenaje a la memoria de su compañero de armas. Probablemente, él fue el último sobreviviente soviético de aquellos acontecimientos históricos. Falleció en 2010, a la edad de 87 años. El estadounidense, que estrecha la mano de

Sylvashko en la famosa foto,

Robertson, falleció en 1999. Todos los que sellaron el Juramento del Elba hace 69 años ya han fallecido. Pero la Guerra Fría aún se está librando sobre el planeta, fermentando en las zonas calientes de muchos conflictos regionales.

Otros enlaces de interés

«Встреча на Эльбе» (Encuentro en el Elba) – la

película de propaganda soviética de 1949, en ruso, que desarrolla el encuentro en el Elba y la posterior división de Alemania en zonas de ocupación:

https://video.yandex.ru/users/cuvschinov-a/view/2478/Una entrevista de 1980 con

Joe Polowsky por el galardonado autor estadounidense y notable personalidad de la radio Studs Terkel:

http://studsterkel.org/results.php?summary=Polowsky–

Parte 1 y

Parte 2.

«Встреча на Эльбе» (Reunión en el Elba) – este documental de 1990 en ruso trata de las celebraciones del 45º aniversario del encuentro en Alemania :

http://net-film.ru/film-20264/«Алтарь Победы : Встреча на Эльбе» (El Altar de la Victoria: Reunión en el Elba ) – este documental del 2009, en ruso, de la NTV sigue curiosamente la línea crítica de la película estrenada 60 años antes:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DB4Rj3EoIhI«Встречи» (Encuentros) – documental de 2011, en ruso, sobre

Igor Belousovitch, nacido en Shanghai, hijo de emigrantes rusos, que formaba parte de la patrulla de

Craig:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQDcJG-ms2o

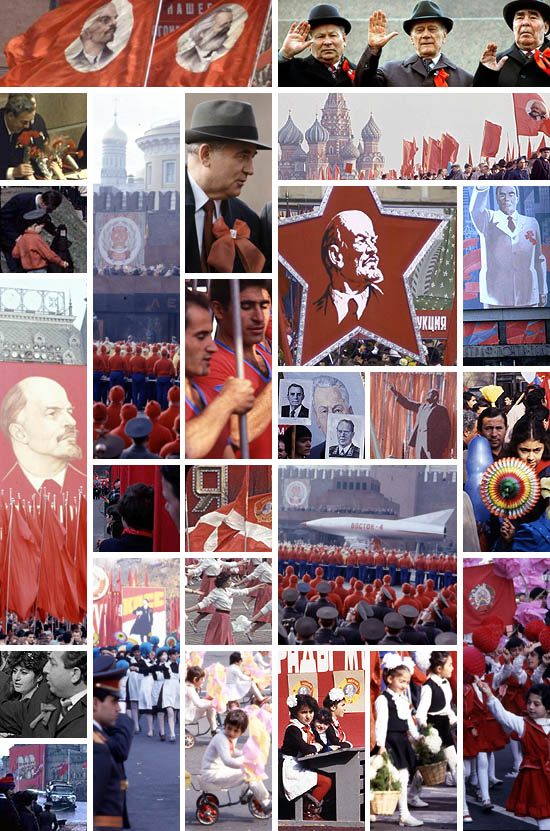

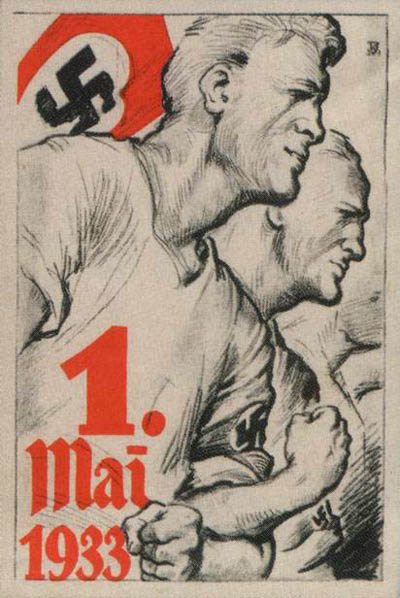

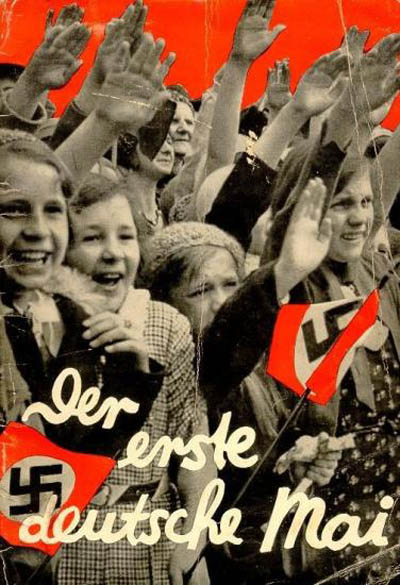

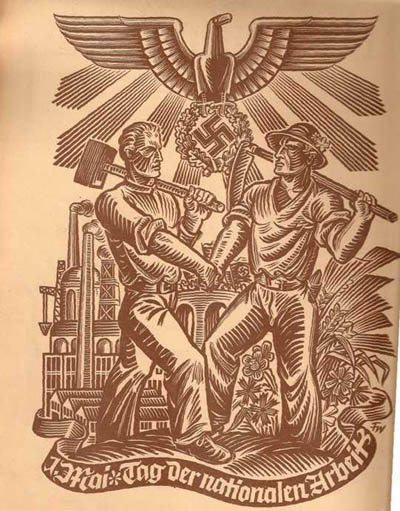

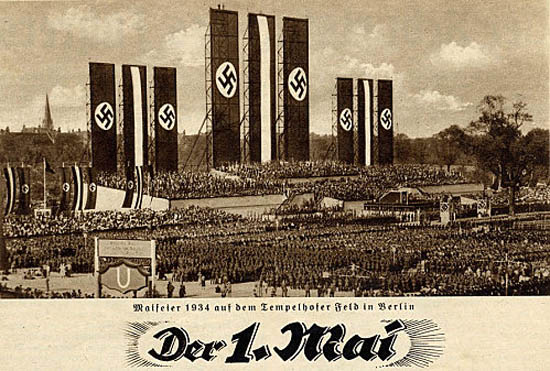

The last May Day parade, I think, was in 1989. In 1990, a few weeks after the first free elections, we already went to the picnic organized instead of it in the City Park, for the assessment of the situation of the winning and losing parties, combined with sausages and beer. Only the thirty-year old pictures of Alexander Nankin’s just released nostalgia post have recalled again, what a magnificent event was that profane liturgy of the power, coreographed on the basis of archaic models.

The last May Day parade, I think, was in 1989. In 1990, a few weeks after the first free elections, we already went to the picnic organized instead of it in the City Park, for the assessment of the situation of the winning and losing parties, combined with sausages and beer. Only the thirty-year old pictures of Alexander Nankin’s just released nostalgia post have recalled again, what a magnificent event was that profane liturgy of the power, coreographed on the basis of archaic models.

Hace casi un año anoté unas

Hace casi un año anoté unas

Sometimes I feel the need to simply pick out and insert here some pictures from the

Sometimes I feel the need to simply pick out and insert here some pictures from the

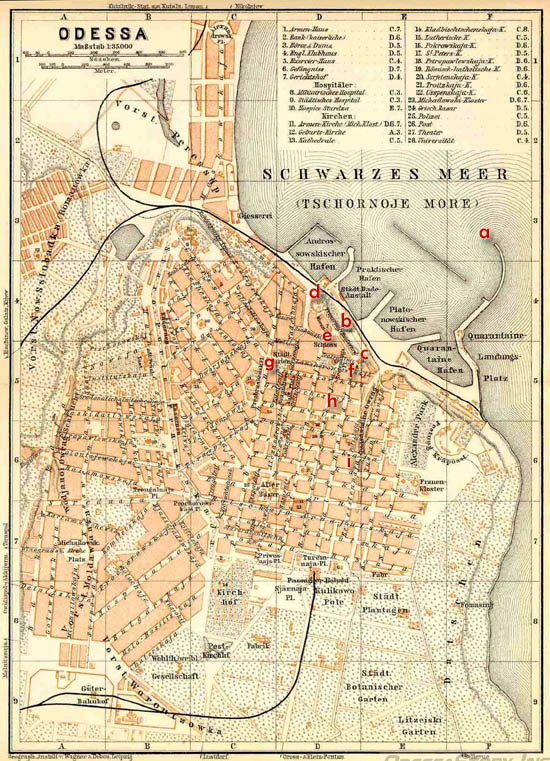

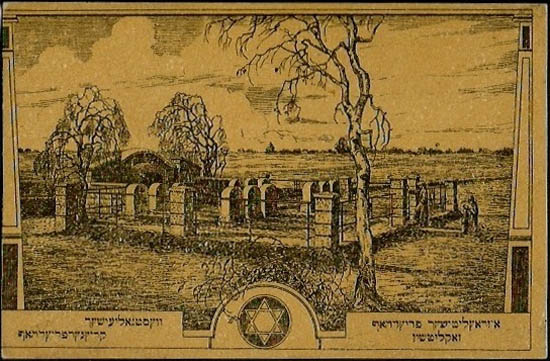

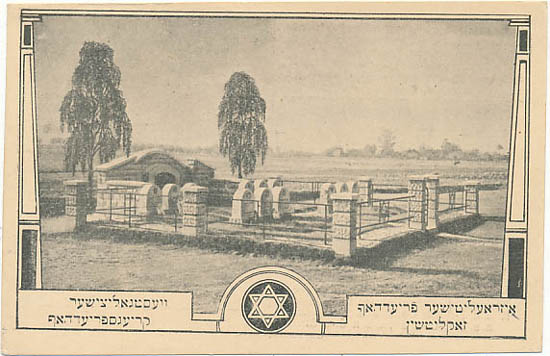

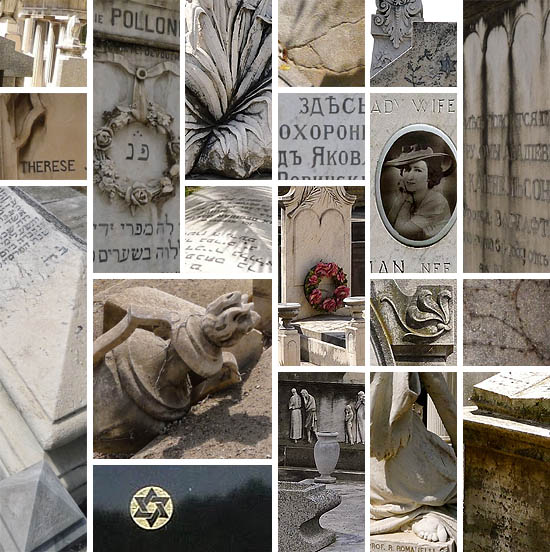

The yellow square on the forehead of the witch-face turned aside is Bobowa in southeastern Poland, at the Carpathian foothills. Here we are, just in the smaller eye of the cyclone, which has been rotating around for two days, incessantly pouring rain on the site of Sienkiewicz’s Deluge. We are heading to the former shtetl, one of the most beautiful intact Jewish graveyards of Poland. The graves look down from a high hilltop over the village to the valley of Biała, so that neither the Wehrmacht, nor the local people were later in any mood to mess with the removal and recycling of the stones, as they did in many other cemeteries.

The yellow square on the forehead of the witch-face turned aside is Bobowa in southeastern Poland, at the Carpathian foothills. Here we are, just in the smaller eye of the cyclone, which has been rotating around for two days, incessantly pouring rain on the site of Sienkiewicz’s Deluge. We are heading to the former shtetl, one of the most beautiful intact Jewish graveyards of Poland. The graves look down from a high hilltop over the village to the valley of Biała, so that neither the Wehrmacht, nor the local people were later in any mood to mess with the removal and recycling of the stones, as they did in many other cemeteries.

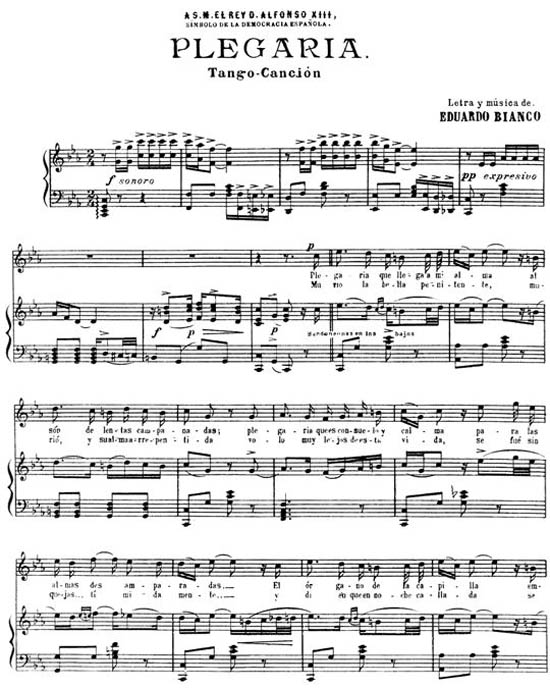

This is a story which began almost exactly 100 years ago, in September 1914. Francisco Canaro’s lucky break into the ranks of most-listened-to tango orchestras was catalyzed by his invitation to highlight Primero Baile del Internado, the First Ball of Medical Interns, which marked the end of the spring break in the School of Medicine. The interns of Buenos Aires found their inspiration in Paris, in traditional medical students Bal de L’Internat held at Bullier Hall. To this rancorous celebration at the famous Palais de Glace, Canaro premiered a tango titled Matasano, “The Slayer of the Healthy” (as the medical students were humorously called), dedicated to Hospital Durand in Caballito neighborhood. The following year, Canaro premiered tango “El Internado”, “The Intern”, at the Intern’s Ball.

This is a story which began almost exactly 100 years ago, in September 1914. Francisco Canaro’s lucky break into the ranks of most-listened-to tango orchestras was catalyzed by his invitation to highlight Primero Baile del Internado, the First Ball of Medical Interns, which marked the end of the spring break in the School of Medicine. The interns of Buenos Aires found their inspiration in Paris, in traditional medical students Bal de L’Internat held at Bullier Hall. To this rancorous celebration at the famous Palais de Glace, Canaro premiered a tango titled Matasano, “The Slayer of the Healthy” (as the medical students were humorously called), dedicated to Hospital Durand in Caballito neighborhood. The following year, Canaro premiered tango “El Internado”, “The Intern”, at the Intern’s Ball.

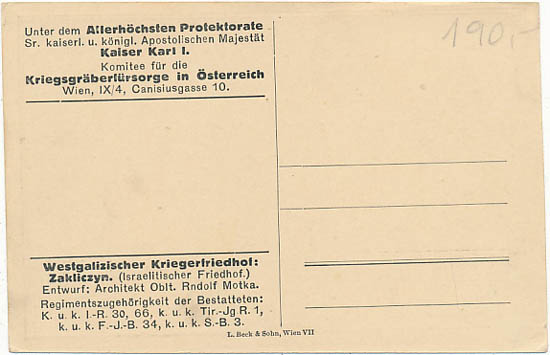

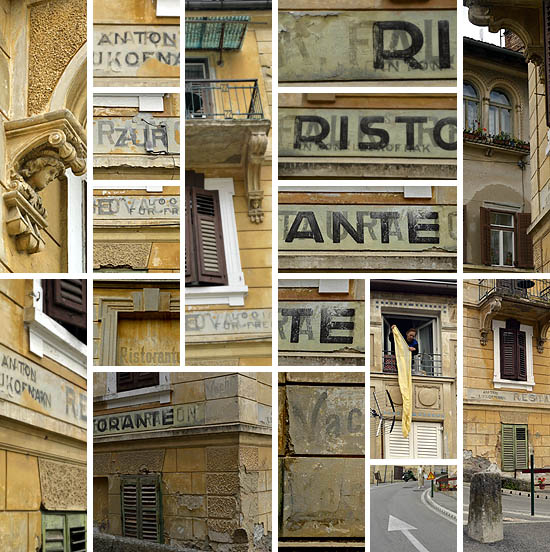

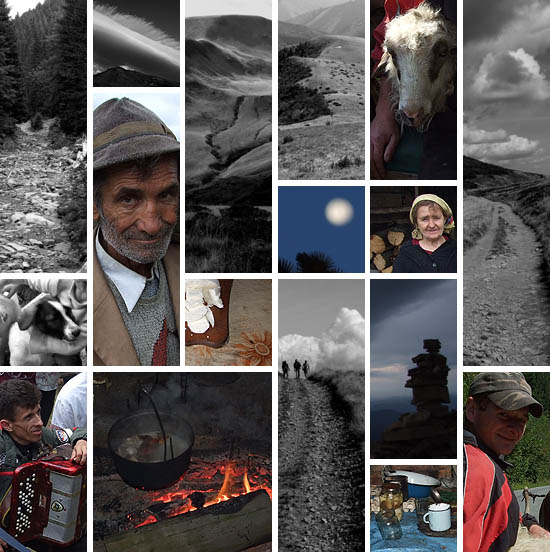

On our second journey, between

On our second journey, between

Des petits cailloux sur les tombes.

Des petits cailloux sur les tombes.

Pebbles on the graves.

Pebbles on the graves.