![]()

![]()

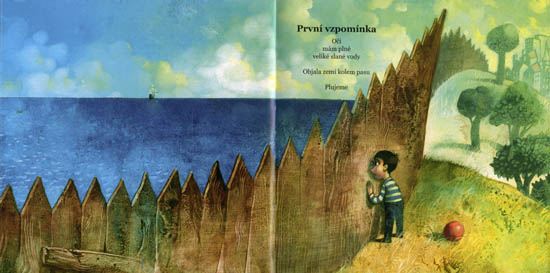

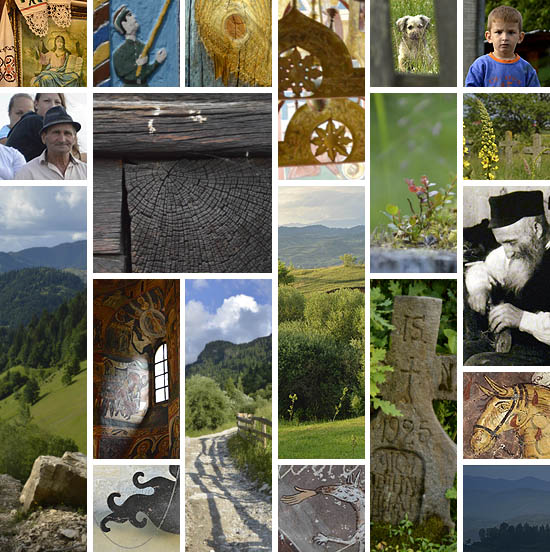

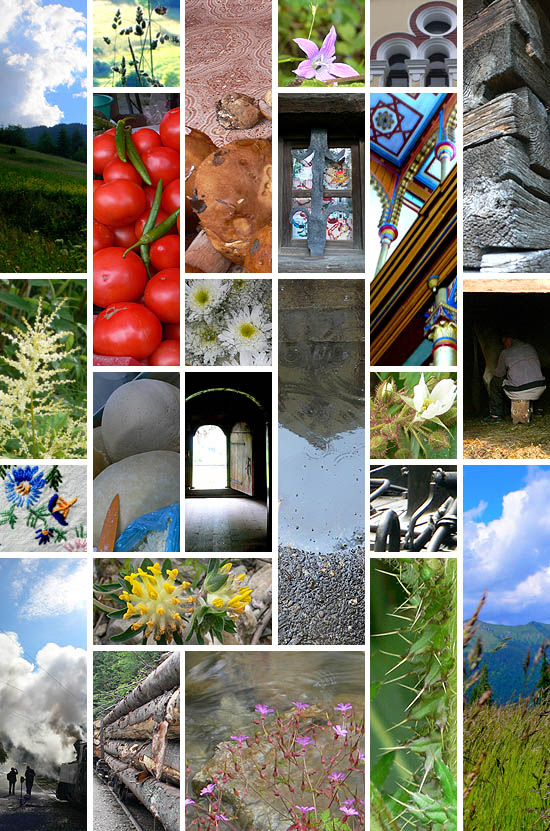

I came to Maramureș for the sixth time, and instead of becoming an everyday experience, it seems always richer and more inexhaustible, the far-reaching misty highland, whose soft green slopes invite you to lie down, to set out, to get lost in them, the wooden churches and cemeteries, whose paintings and carvings preserve a fascinating visual world moulded from archaic roots, eastern and western iconography, and exuberant local imagination, the labyrinths of the villages built of wood, and the people, who with an admirable energy maintain from day to day the small worlds entrusted to them. The following reports and images, composed by the participants of our trip, prove that this land has such an impact not only on me.

And those who feel similarly by the end of the reports – or has already felt this way, but there was no space any more in the minibus –, are welcome to the repetition of the tour

from 20 to 24 August. With even richer experiences, because I also feel the need to go there previously, for the seventh time, to explore the highland alone and on foot. You can apply at

wang@studiolum.com, and you can soon read the reports at río Wang.

Studiolum

![]()

Maramureș

![]()

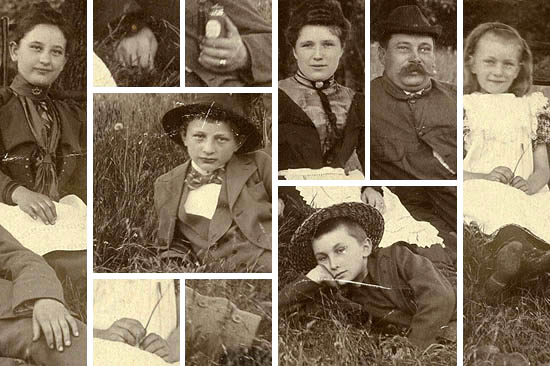

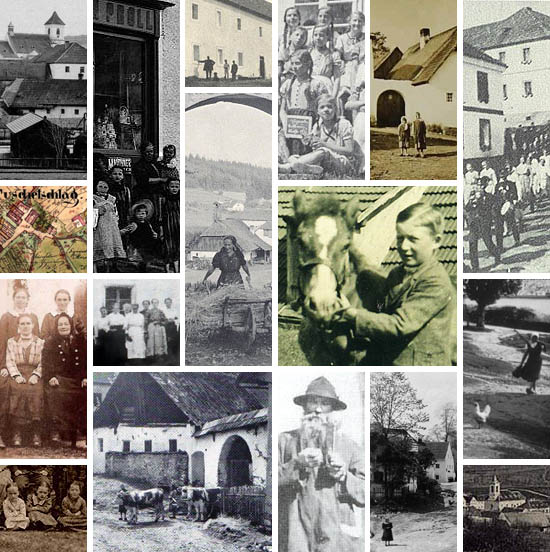

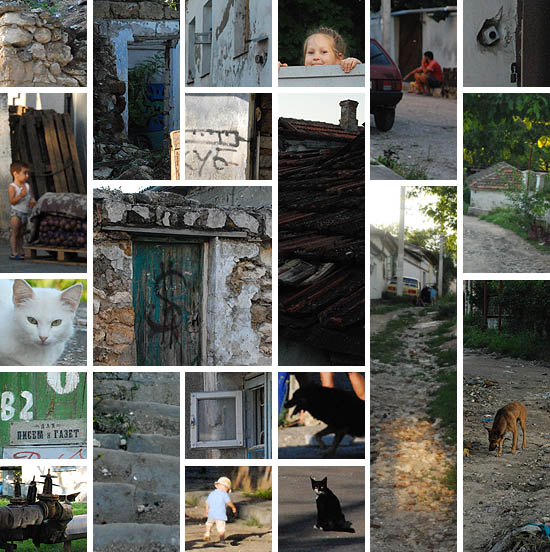

Máramaros/Maramureș, Kárpátalja/Subcarpathia, Máramarossziget/Sighetu Marmației, Huszt/Khust, Nagyszőlős/Vinogradov, Técső/Techiv, Rahó/Rakhiv. Patchwork names of my paternal family. Collected family crumbs. Terrible stories, unspoken words. Random insights, conscious investigation. And, in the meantime, similar orgies of scents, sights and colors in the similar sites of my childhood: at the market of Keszthely, tomato heaps, mushroom wonders, Aunt Galic’s milk stall with cheese and cottage cheese, sold by kilo. Just like at the market of Sighetu Marmației. A sea of flowers in the open meadow around the garden. How great it was to lay down in it! Now, here, I did not lay down on the grass, I already regret it. The mountains around Keszthely, and the sweet landscape of Balaton Uplands beyond the mountains fits together in my imagination with the soft green waves of the mountains of Maramureș. The real memories with the imagined past, built up from fragments.

![]()

![]()

![]()

D. Kati

![]()

Blue and green

![]()

I close my eyes: I remember blue walls and graveposts, the fairy blues of the Voroneț monastery and the merry cemetery of Szaplonca/Sapânța. The Last Judgment on the external wall of the monastery is a huge comics, if we did not read it together, I would not understand half of it. Every soul is weighed in the balance, but the non-Orthodox should not even stand in the row, they have no chance. A wonderful work of art, but with a gloomy and frightening message: there is no forgiveness. On the graveposts of the merry cemetery, small still pictures on uneventful lives and tragic deaths. The inscriptions beneath do not spare with the virtues of the deceased, and do not conceal their frailties. The naive representations convey a reassuring message: anyone you were, you were one of us, you belong to us, we remember you.

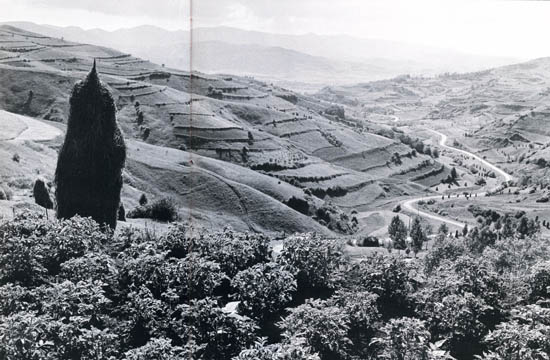

I open my eyes, ouch, I am at home. I quickly close them again: I remember green slopes and meadows, the angry green of the fresh hayfields and the golden green of the late afternoon hills of Maramureș and Bukovina. The landscape is endless, there is no balancing, no passing away. I could watch it forever.

![]()

![]()

![]()

R. Kati

![]()

The Sinistra Zone

![]() “I arrived on a spring day (…) at the Baba Rotunda Pass, from there I saw for the first time those proud peaks, in whose shadow I later almost forgot my previous life. The Sinistra Basin opened in front of me, in the orange light of the afternoon, with long, sharp shadows. Dark willows accompanied the river bends at the bottom of the valley, a sparse row of houses winded on the other bank, shingle roofs glittered on the far away sunny slopes, and in the background, over the black collars of pine forest shone the icy towers of Pop Ivan and Dobrin.

“I arrived on a spring day (…) at the Baba Rotunda Pass, from there I saw for the first time those proud peaks, in whose shadow I later almost forgot my previous life. The Sinistra Basin opened in front of me, in the orange light of the afternoon, with long, sharp shadows. Dark willows accompanied the river bends at the bottom of the valley, a sparse row of houses winded on the other bank, shingle roofs glittered on the far away sunny slopes, and in the background, over the black collars of pine forest shone the icy towers of Pop Ivan and Dobrin.

The peak just emerging from the pine forest already belonged to the Pop Ivan range, you could see from it far away, beyond the border, the consecutive blue ranges of the Rusyn forest land. A some emerged from behind the last hills, perhaps from the far away waste land. The eastern sky, as if night were approaching, was covered by purple curtain. As the sun rose, the remote colors became duller, (…) and the valleys were filled with the opalescent glow of the afternoon…”(Ádám Bodor: The Sinistra Zone)

We were already on the way, when I suddenly realized that we are going to

the Sinistra Zone. That is to say, to the real place, which was transformed into the Sinistra Zone under the pen of Ádám Bodor. But in the real place I have felt nothing from the depressing, dark world of the Zone. A harmonious, peaceful countryside, with open and friendly people. Is there hope…?

Dorka

![]()

Summer

![]()

A summer journey into the wild reaches of Europe takes us to a land of dense forests, golden sun rays, meadows spangled in wildflowers, and whispering rivulets; hemmed in by walls of mountains, as if willfully hiding itself from the outside, where today reigns. Once our modern conveyance has breached the mountain pass, we find this shrouded terrain teeming with crowing roosters, goats, barking dogs and livestock of all sorts; sheep and their keepers; horse-drawn wagons, and the human natives going about their business in their

characteristic dress.We look out over a sfumato landscape of fruit trees, tombstones and grassy mammoths of drying hay, wooden churches and painted monasteries, a verdant landscape of fertile rising land receding into the morning mist. The mountaintop hooks a cloud, and the high wind deforms it into a long white streak like a comet’s tail. Women in black, faces framed in gray hair and deeply scored with hard-earned wrinkles, sit and chat on outdoor benches along the roadside, smiling faintly or looking curiously as we pass.

During a pause in our journey, I and others sit in a bench next to a woman like this, who carries on chatting with us. She knows we cannot understand her, she cannot understand us, but her happy appreciation of the absurdity of the situation was evident as she repeated phrases, and commented to herself, it seemed, about our non-understanding, yet remained accepting and friendly in expression and gesture. This said more to me than any exchange of social pleasantries ever could.

Another day, a steam train on narrow-gauge rails huffs and pants up the mountain, alongside a transparent stream of mountain water. The asthmatic beast earns part of its keep in hauling timber; the other part in hauling tourists and train-fanciers up and down for a morning’s joy ride. For my part, the wheezing, lurching and clanking was an unfolding symphony composed collaboratively by those who engineered the train and its wagons, together with the steady wear of time and use, which, in loosening fittings and slowly rounding the sharp corners of formed metal, lent it a special character.

On our way back to Hungary, we pass through Bistriţa and cross the Borgo Pass. Those

familiar with Dracula lore may recognize these as the sites of important narrative moments in the Bram Stoker novel. This Western story seems set more in Western hallucinations about the dark reaches of Europe than in any actual place called Transylvania. In confronting the real territory, the dread and darkness of a land where blood-parasites dwell give way to an appreciation for how rich and full is the life of this country.

Lloyd Dunn

![]()

Transcendence

![]()

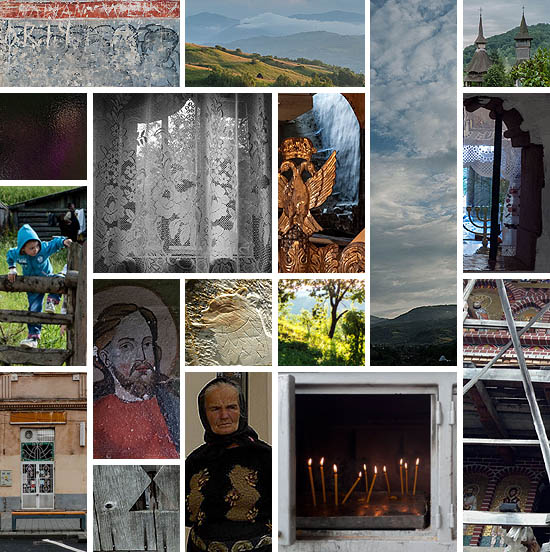

The Maramureș–Bukovina trip was above all a dislocation into a very different world, about which I hitherto had only faint ideas and fantasises. They have now got forms, and very beautiful forms at that.

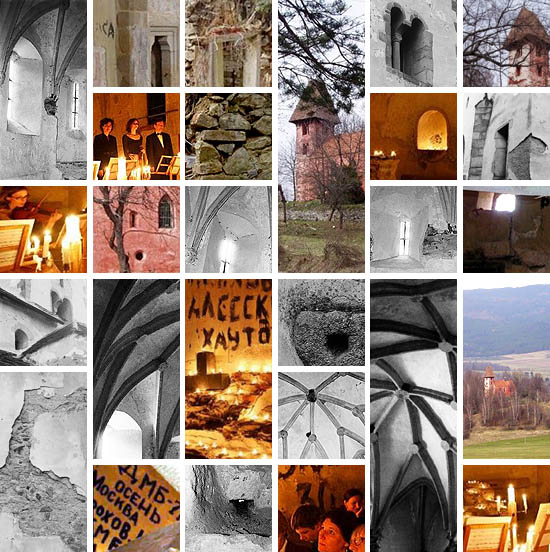

The whole region is so archaic, so much embedded into nature, it is imbued with spaciousness, colors and lights, a thousand shades of green, mountains, passes, valleys, lines, verticals and horizontals, golden hours with mountain chains, waterfall with horses, the geometry of the haystacks, the bright brown of the wooden churches, the turquoise blue of the monasteries.

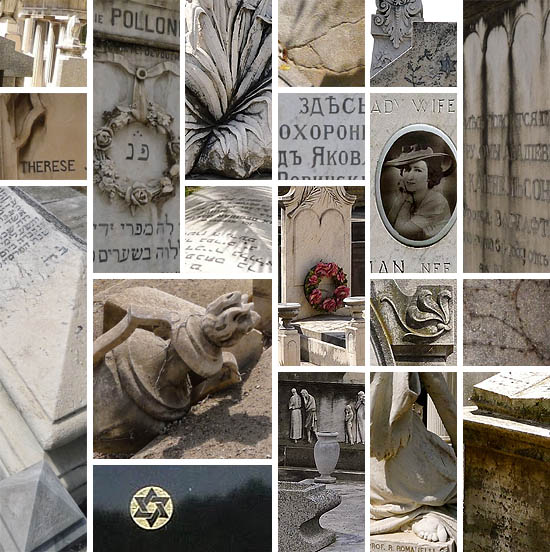

And the other world within the other world: the spaces of transcendence and sacredness. Orthodox mass in the monastery of Putna (even a few minutes were of elementary force), churches, synagogues (and their places), the cemeteries. Intertwining of awe and humor, intimacy and perspective in the cemeteries, both in the Christian (the merry cemetery in Szaplonca/Sapânța and the sweetly naive one in Andrásfalva/Măneuți) and the archaic Hasidic ones (the dilapidated cemetery in Jód/Ieud and the one with stone lions and interwoven hands in Gura Humorului). In the garden of I already do not know which monastery (perhaps the last one, in Arbore) it was necessary to lie down a little bit in the grass, and it was not at all easy to get up.

And then the cities – the main squares of Szatmárnémeti/Satu Mare and Nagybánya/Baia Mare, the only surviving synagogue (out of the eight ones) of Máramarossziget/Sighetu Marmației, Elie Wiesel’s study room, the main square bookstore, the heavenly

ciorba de burta soup at the market, on the way home the bustling main street of Beszterce/Bistrią. The unique atmosphere of the accommodations and breakfasts in Barcánfalva/Bârsana, Borsa/Borșa, Putna (how crispy the mere names are!), the fried doughs, jams, loaves with fresh sheep cheese, plum brandies. The kitten who joined us on the walk in the monastery complex of Bârsana.

![]()

Then the “vehicles” – here also, nature and technology, forestry and tourism are together. The trip with the little train of Felsővisó/Vișeu de Sus is one of the highlights. Like a fairy tale, in the beautiful scenery, while loading wood, and enjoying the cranberry brandy in the “buffet wagon”. Then the cable-car, now we can watch the landscape from above, with a small agoraphobia, but great admiration.

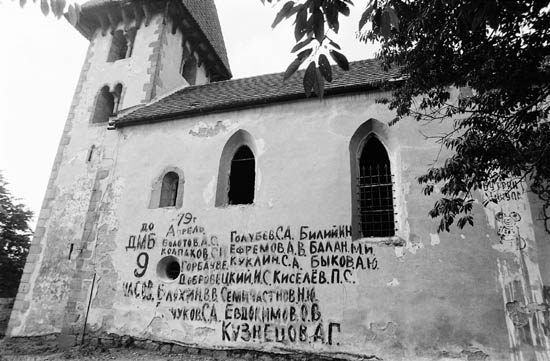

The confluence of the palettes of cultures and eras, their writing above each other (sometimes literally). Such unlikely coexistences, like the small café of the Elefant House in the last Jewish owner of the sawmill plant in Vișeu de Sus, with the best coffee of the journey (where the railway ticket collector now excels as a barista), and the room opening from it, which is a museum documenting the one-time life of the Jews of Vișeu in heartbreakingly beautiful photos. Or the 16th-century frescoes of the Moldovița monastery, with the already museal layers of graffitis on it, including the signs of the 19th-century law student Albert Blanc and of a certain Nussbaum (perhaps one of my matrilineal ancestors?)

And you cannot ignore how much more you see if you also know the layers and histories behind what you see. The way is intervowen with images, meanings, symbols. In the wake of the fascinating guiding, the icons of religion, history and art are enlivened within their own complex system, as a not merely lexical (although based on a huge material) knowledge about images, buildings, movements of populations, names, places and one-time places. And this in the atmosphere of general attention, humor, flexibility, and good (though sometimes slightly “time-optimistic”) daily rhythm, in a pleasant international company, with whom you can also talk, play and sing along. Five days of real inspiration.

![]()

![]()

Anna

![]()

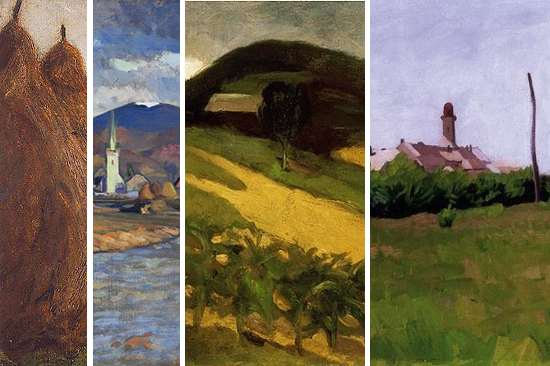

A painted region

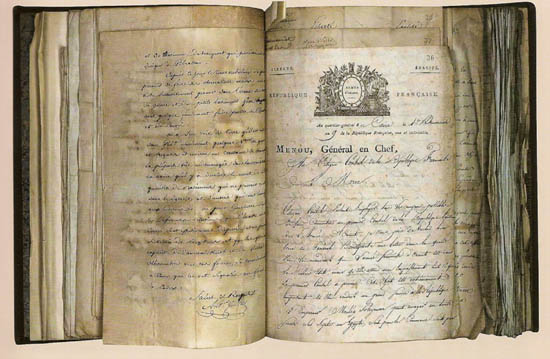

![]() “Nagybánya, Hotel King Stephan”. Posted on 29 November 1917, from here

“Nagybánya, Hotel King Stephan”. Posted on 29 November 1917, from here![]() Ten years later. “Baia Mare – Nagybánya, Hotel «Ştefan Vodă» Szálloda.” Edited by Librăria Kovács Bookshop, 1927. Posted on June 1929, from here

Ten years later. “Baia Mare – Nagybánya, Hotel «Ştefan Vodă» Szálloda.” Edited by Librăria Kovács Bookshop, 1927. Posted on June 1929, from here![]()

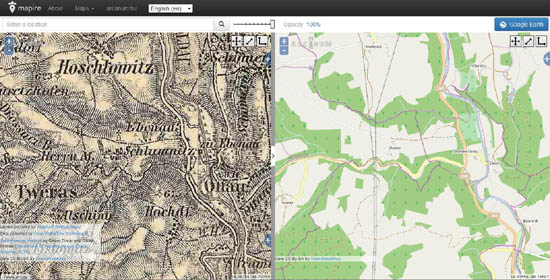

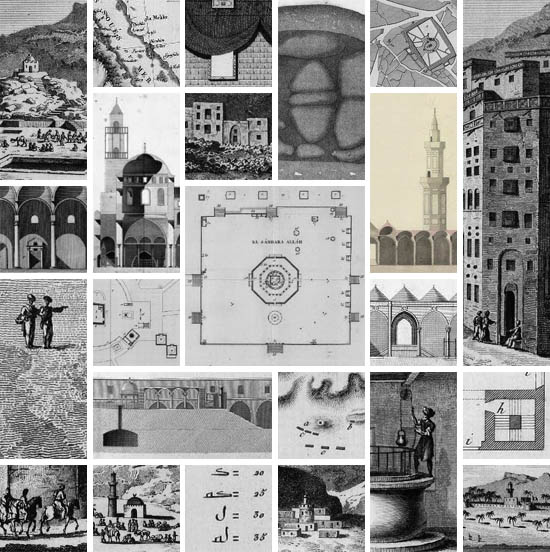

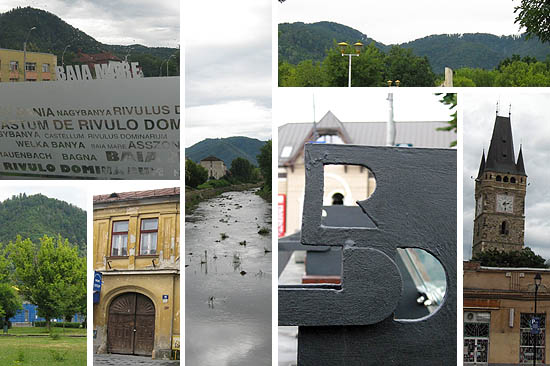

Nagybánya, Baia Mare, Frauenbach/Neustadt, Rivulus Dominarum, in its old Hungarian name Asszonypataka (Women’s Creek), also suggested by the Latin name (but already forgotten by the times of the topographer

Elek Fényes…). “It lies in a beautiful and healthy region”, he writes, and you cannot dispute that statement even today. It was not disputed by the Hungarian naturalist painters in the early 20th century either. It is probably not a coincidence that in 1896 the members of the Hollósy painters’ circle, returning from Munich, founded exactly here the

artists’ colony which later became the cradle of modern Hungarian painting. The idyll of gentle mountains, turn-of-the-century

plain air.

![]() Group photo of the Nagybánya artists (1897). “Back row, left to right: Sándor Nyilasy, Gyula Szeremley, Sándor Kubinyi, Béla Iványi Grünwald, István Réti, Simon Hollósy. Front row, left to right: Valér Ferenczy, Károly Ferenczy, Béla Horthy, Cézár Herrer, Pál Benes.” Text and photo from here.

Group photo of the Nagybánya artists (1897). “Back row, left to right: Sándor Nyilasy, Gyula Szeremley, Sándor Kubinyi, Béla Iványi Grünwald, István Réti, Simon Hollósy. Front row, left to right: Valér Ferenczy, Károly Ferenczy, Béla Horthy, Cézár Herrer, Pál Benes.” Text and photo from here.This was then shortly followed by several other artists’ colonies in Miskolc, Szentendre, or Budapest (the MIÉNK – Circle of Hungarian Impressionists and Naturalists). In Budapest even a café of the same name worked at the corner of József Boulevard and Bérkocsis Street. It is not known whether there was any connection between the artists’ group and the café; in any case, the latter far survived the former, whose members after two years already worked in other groups. But we left all this behind us, somewhere in the west, and now we are heading east.

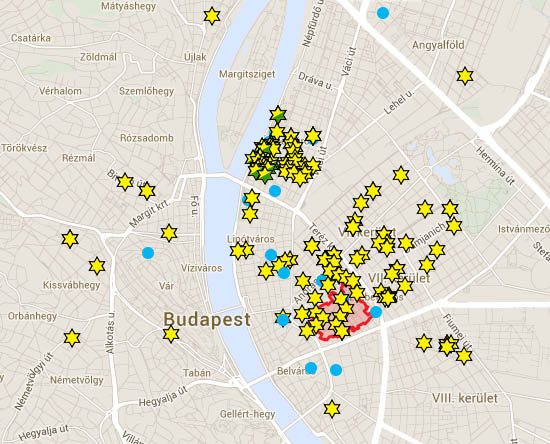

Before becoming an artists’ colony, the city was a major gold mine for a long time, and also one of the most important mints of old Hungary, immediately after Körmöcbánya/Kremnica. Today it is the seat of Maramureș county, although the historical and geographic Maramureș begins only later, Baia Mare is just its entrance-hall. But Maramureș is not any more what it was: now the border runs along the Tisa river, once the source of life for the whole region, thus cutting in two halves this formerly undivided area.

![]()

Of course, Maramureș is still living on along the left-bank tributaries of Tisa, and the landscape, due to the relative closeness and to the domestic tourism, has retained its archaic features. Perhaps this is why, in spite of its apparent poverty – and in sharp contrast to the Ukrainian Maramureș – some kind of peace and harmony pervades the whole region, from Dióshalom/Șurdești to Felsővisó/Vișeu de Sus and further, beyond the Carpathians, in the former Moldavian province of Bukovina, which

lost its capital city. Perhaps the only exception is the somewhat upset town of Máramarossziget/Sighetu Marmației, but then what should be a city like, of which the other half belongs to a different country?

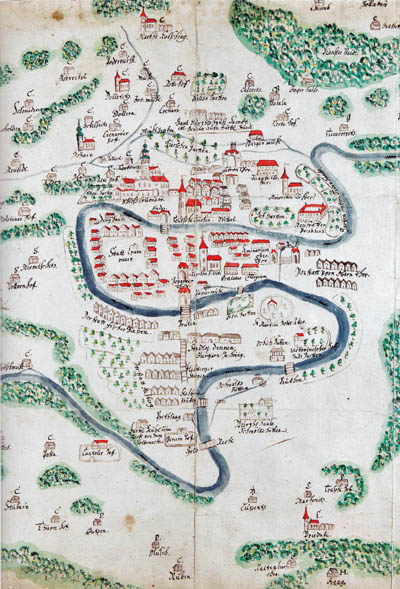

By following the Ariadne’s thread of the painted wooden churches we try to orient ourselves in this labyrinth, divided by the tributaries of Tisa and bestudded with little villages. The wooden churches were painted on the model of the Bukovina monasteries. Now we move in a reverse chronological order, from the old to the older. This has always been a busy route in the history, the two regions were bound together with many ties. Once the first Vlach

kenéz– tribal leaders – came from the other side of the Carpathian mountains with their mixed Slavic and Vlach people to populate the forest land of Maramures, and decades later the voivods Dragoș and Bogdan returned along the same way, on royal command, or guided by ambitions of independence, to establish the Moldavian principality. Dragoș’ descendants also lived on as Hungarian and Polish aristocratic families. Later Jews arrived from Galicia, first Orthodox, then Hasids. Their memories are now preserved only by the cemeteries – Jód/Ieud, Szaplonca/Sapânța, Gura Humorululi and others –, the orphaned synagogue in Sighetu Marmației, and some museums. Nevertheless, at the sight of the romantic Maramureș landscape one has the strong feeling that at any point a

mountain Jew can pop up, even if Stanisław Vicenz wrote already in the 1910s on the other side of the mountain that “there has not been such

species for many years either in Jaworowo nor in Jasienowo” – well, then today…

In the place of former mountain Jews: Romanian lumberman at the Waterfall of Horses

Bukovina, the peace of Orthodox monasteries, the sonorous liturgy. The end of the known world, at least if we think about the Last Judgment compositions on the external church walls. The ceasing of time, the last muster of the zodiacal signs. A detailed, highly captivating display of what somewhere deep troubles us all. And the blue of Bukovina might be a worthy pair of the

Isfahan blue, for the time being admire only from afar by me.

The whole region is full of animals: animals along the roads and on the frescoes, the latter often exotic, and quite often enjoying the companionship of strange, hardly believable creatures in paradisiacal landscapes: lions, dragons, centaurs, whales, elephants. Among the latter, special mention deserves the one in Vișeu de Sus, at the terminal of the

mocăniţa.Dani

![]()

From the goat cheese to Lorca

![]()

At the market of Máramarossziget/Sighetu Marmației we eat divine ciorba de burta. While waiting for the soup, we hurry out to the cheese market with Kati. Sheep cheese, goat cheese, cow cheese, cottage cheese, sour cream, bryndza, you can buy all. A burly Romanian lady cordially invites us to taste. We explain that we are just looking around, and that we would come back after lunch. Although she knows a few words in Hungarian, which she eagerly lists to us, we cannot understand each other. She beckons to us to follow her. She accompanies us to a Hungarian saleswoman, who translates our message into Romanian. After the ciorba is over, we go back to the cheese stall, the lady is already waiting for us with a broad smile in the middle of the market. The business is done, we purchased one and half kilo of cheese for only twenty-four lei (less than seven euros). And there were not even the slightest traces of any Romanian-Hungarian antagonism.

![]()

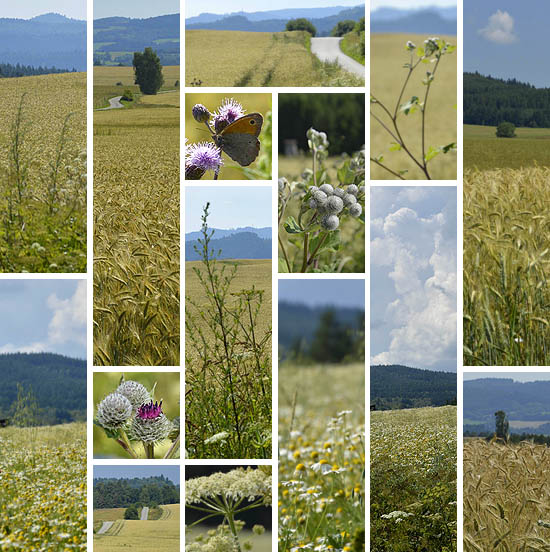

While drinking kefir, Lloyd says he has never taken such a good kefir anywhere else. I tell him, it is probably because the meadows and pastures are full of wild flowers and herbs. I saw at least three types of thyme, there was mint, many types of sage, milk rennet, St John’s wort, bugloss, camomile, feverfew, thistle, blooming sally, and many other herbs unknown to me, not to mention the former Hungarian cemetery of Andrásfalva/Măneuți, where the wives of Gyuri, Laci and Dani peacefully rest under the thick green parsley.

![]()

We enter the Sephardic synagogue of Sighetu Marmației. The Sephards were Jews expelled from Spain, who preserved the living medieval Spanish language, the Ladino. During the Reconquista, Catholic Ferdinand and Isabel drove out those Jews who did not want to convert to the Catholic faith. Many of them found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, this is how they also arrived at the Balkans. They came to Maramureș probably during the Ottoman conquest. We may not know who of us has some drops of Spanish blood.

![]()

The sentence of my dear poet, Lorca is relevant here:

“Yo creo que el ser de Granada me inclina a la comprensión simpática de los perseguidos. Del gitano, del negro, del judio, del morisco, que todos llevamos dentro.”– “I think that my Granada roots urge me to sympathize with the persecuted. With the black, the Gypsy, the Jew, the Moor we all carry inside.”

![]()

P. Eszter

![]()

The Steam Railway

It was very interesting to see the narrow-gauge steam railway with wood-fired engine, the last working forest railway in Europe.

The water was refilled from a little pond by the side of the track and the points are changed manually. Engine 764.408 is quite new, built in 1986, but some of the other engines were built in the 1920’s.

Hilary

![]()

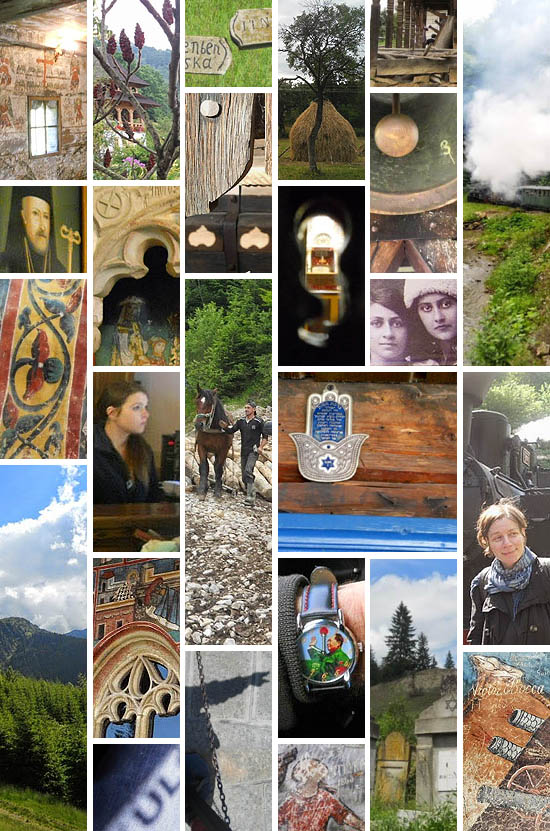

We saw a lot many beautiful things

Well, we left. Quite unprepared. We only had a look at Tamás’

road map, along with the photos, of course. We were curious of the company, and the painted monasteries of Moldva. Especially I, as I told it in my self-presentation.

I tried to conceal my superiority with which I told myself that I had already seen Gothic monasteries and frescoes, and I had also traveled by steamer in the beautiful valleys of the Austrian Alps.

The trip was long, but then we were happy to see the main square of Nagybánya/Baia Mare, the palace from where Erzsébet Szilágyi wrote her legendary letter to her son King Matthias Corvinus, and to greet the mountain where modern Hungarian painting was born.

![]()

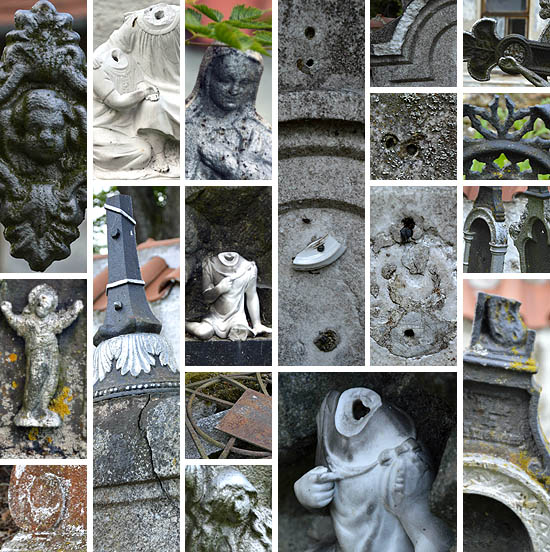

Then we arrievd to the first wooden church built of giant logs (I think it was Dióshalom/Șurdești) with the tin Christs on its wall. And I suddenly forgot my pride of “I have already seen such a thing”. Christ on the cross, and the two little doves above, and the little angels below, and the half-worn off tiny flowers, exudes so much naive charm, that one could not but romantically gaze at it. And this was still nothing in comparison to the next two wooden churches. Of course, there was architecture and structure and great and well-worked timbers and beams in them, but I was caught again by the pictures. Because they beautifully told to my childlike soul, how Mary went to heaven, what happened to Jesus, how ugly evil men tortured him, and how little Adam and Eve played in the paradise garden. Is it not as a fairy tale told to children?

And then my soul cheered up, and from now on everything was fine.

On the other hand there I realized the only serious structural deficiency of the trip, which I am forced to throw in the face of Tamás, because I had not expect it: that YOU ALWAYS HAVE TO GO FURTHER!

So we went further even from Desze/Desești, and we had accommodation in the nuns’ monastery in Barcánfalva/Bârsana.

The next day it was raining sometimes, but Maramureș is even so beautiful.

![]()

For example, the wonderful garden of the monastery, where you could hear the loud munching of the vegetarians even in the rain. And the merry cemetery of Szaplonca/Sapânța, where it started to rain again always at the most beautiful graveposts, but at the bells it stopped. The merry cemetery is a strange thing. Of course, its funny inscriptions are more human than the usual pious epitaphs, which are the same everywhere, and the ones here help to think more times about the deceased, but I cannot imagine on my tomb an inscription like “Here lies Ferkó, the ugly old stranger, who was struck by a baby carriage while gazing at the frescoes.”

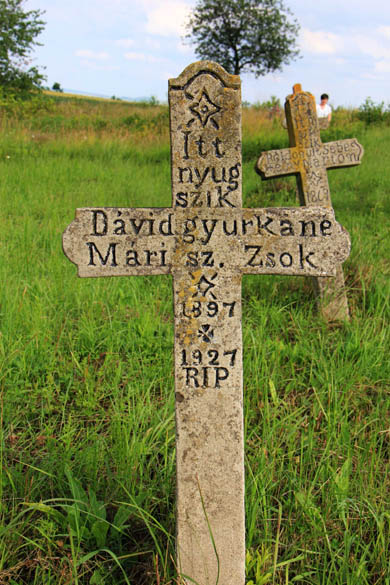

Then along a sparkling stream, before romantic tiny wooden houses we climbed a drenched grassy hill to the Hasidic cemetery, which was neither sparkling, nor romantic or merry.

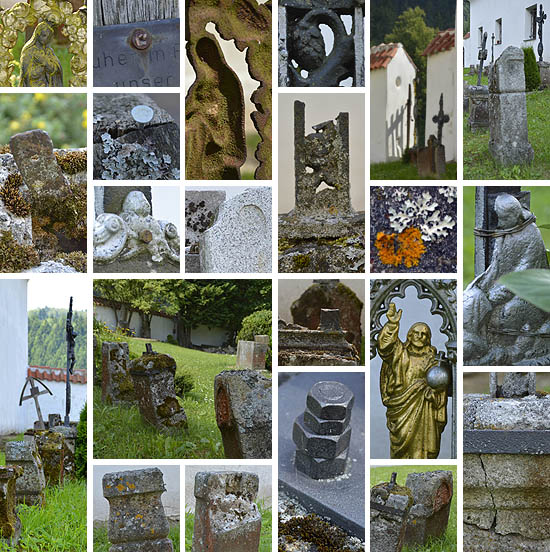

Dilapidated, decaying stone, with barely visible writing. So we were wandering among the tombstones, and listening to the stories of Tamás, which made you think about many things. But they did not make you sad, for in this beautiful landscape one cannot be sad.

The rain also accompanied us to the cemetery of political prisoners, and to Sighetu Marmației itself.

We visited the former Communist prison, and the main square with the bookshop, we found the synagogue and we could even enter. But by then I already felt dizzy. Because Tamás told us about local history, how the Jews were deported and murdered, how the Hungarians were deported by the Romanians and the Romanians by the Hungarians, the Poles by the Ukrainians and everyone else by the Communists. It seems that during the past centuries this part of the world was a restful place only for a couple of weeks, and then always happened something. Now I’m sure to have mixed some details, but fortunately nobody knows this except for Tamás. The most surprising is that, in spite of all this, or perhaps exactly because of this, incredibly many different cultures have evolved and survived here. It was the relics of these many centuries, produced throughout centuries, which we watched for only four days, instead of watching them for four months or years.

![]()

The culture, of course, also included the market and the delicious ciorba soup, before we went further to Sajómező/Poienile Izei, the next wooden church, where not even Tamás had ever been. The advantage of this – and I really enjoyed it in the painted monastery of Arbore – that Tamás always takes a lot of pictures in the places where he had not been before, and during this you can gaze at the frescoes for a long time. But now we are only at Jód/Ieud, the oldest wooden church and the

cemetery around it. Now we already felt at home among the old graveposts, many things seemed familiar, and so you could be even more happy for them.

Then we arrived at Borsa/Borșa, our accommodation, where we were received with wonderful plum brandy, as well as with a fine dinner.

Then came the hiking day, about which many beautiful photos will speak. My greatest impression was that, leaving the smoking train, we merrily entered a charming café, where in the next room there was a chillingly objective exhibition about the deportation of the Jews of Wischau. But even this could not spoil the beautiful day.

And on Saturday we finally arrived at the monasteries of Bukovina. The first among them was Voroneț, which was in the best condition among all. “Pars pro toto”, said Tamás, if you saw one of them, then you saw them all. Again he was right, but it is not worth noting, as one does not repeat noting that the snow is white or the rain falls down.

![]()

I fell into the trap that I began to deal with the details. Of course – since it cannot be my fault – it was the fault of Tamás, who spoke to us with an incredible knowledge about the meaning of the various scenes and images. Let it be said in my favor, that I was pleased to recognize some scenes, especially their differences with the Catholic iconography, with the help of Tamás, of course. And I adored the “Byzantine” style, strictly prescribed to the artist, as if they had been 13th-century frescoes, with tiny or local differences in the details.

But retrospectively I also regret a bit that I did not watch it all as a whole thing, by understanding the faith, and – why to deny – the demonstration of power inherent in it. I, Prince Stephen, the mighty and victorious, have built this church, remember me in eternity! Even if this is not a pecularity of Prince Stephen, for almost every castle, fortress and church speaks about this to some extent.

![]()

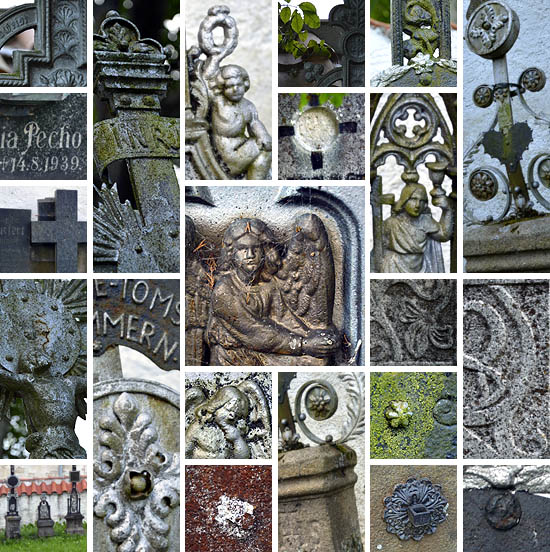

I do not exactly remember the order any more, but as far as I can recall, after this we visited another Hasidic cemetery. This was much more exciting than the previous one, with the several symbolic animals you could study and learn here, from the man-headed lions to the hawks which even Tamás did not know. It was really worth to spend some time here. I was particularly pleased to meet the cemetery supervisor, and old woman, who spoke in an excellent German about the cemetery, that the mother of Joseph Schmidt is also buried here, that the world famous singer was a child here, from here he went to Czernowitz, and from there to Vienna.

![]()

And the rest is even more mixed up in my memories. Because we were in Moldovița, where Constantinople is besieged with non-existent guns, and where the nun explained in a colorful German the scenes, colors, objects and their significance. This showed well, how much Christian symbolism can be read into the Old Testament. And we were in Arbore, where Saint John the Baptist is beheaded, and where I, despite of the presence of my wife, immediately fell in love with the painted Salome. And we were in Humor, where, according to the description, for a hundred and fifty years the roof was not big enough, thus some of the frescoes also faded.

That is a great loss, of course, but as the beautiful poem says:

„De ami egykor

megidézte

ami a kép

törekedése

a málló állagból

kiválik

a fej körül

tovább világít.” | | “But its one-time

inspiration

the picture’s final

aspiration

emerges from the

crumbling plaster

it keeps on shining

as made by the master” |

Then we arrived at Putna, the stern monastery, where we had dinner, and a beautiful Mass with enchanting music, and an evening walk, but all this belongs to the finale.

![]()

And here, as always on the bus, we had another, constant highlight of the trip. You could chat, make acquaintances, talk about the grandchildren and about your youth, and thereby make new frieds. This went on along all the way home, only sometimes we were amazed by the beauty of the landscape or had a hiccup at the

castle of Dracula.In Beszterce/Bistrița we stopped for a short while, a coffee, an ice cream, we also consumed a late Gothic church and a street fair, and then rush back to the bus.

And at ten and a half we arrived at the Heroes’ Square in Budapest. The Fine Arts Museum was unfortunately closed at that time, but that’s okay, because

we saw a lot many beautiful things!Ferkó & Panni, Austria

![]()

The difference

![]()

Of course you could go into the Rumanian Maramureș and Bukovina areas on your own, and see the world heritage wooden and and painted churches with the comment of loud German speaking black nuns. We visited the area with Río Wang/Tamás Sajó, and Tamás makes for us the difference. His historical, political, cultural, religious backgrounds gave this trip a deeper meaning, you long for more.

Highlight for us was the explanation of The Last Judgement, painted upon the Voroneț church exterior, and how is was meant for the masses of simple people, who had to stay outside, to decide on a choice in life.

In 35 years of traveling we have never been “bus people”, but Tamás made the difference, now we are!

Tom & Sarie, The Netherlands

![]()

It was a time travel…

…in a mountainous region, where the meadow, forest and stream had been the treasure and livelihood of the people for several centuries, and where flocks and herds enjoy the freedom of grazing;

…on mountain passes, once crossed by brave traders and conquering armies;

…at centuries old rustic wooden churches, built in the collaboration of the whole village, painted by a skilful local or wandering painter, and which are still beautiful in their naivete and perfection;

…little towns, which a hundred years ago were the bustling places of the coexistence of dozens of nationalities, and which also had an important role in the far away corner of the Monarchy;

…to monasteries evoking history, where the clean tradition still lives on;

…to a mountain rail, which helps the ancient forest management to live on;

…to Hasidic cemeteries, which evoke the respectable culture and erudition of a lost people.

And what was a very pleasant surprise: people appreciating and preserving the past everywhere, because all what we saw, does not speak about destruction, but the surviving traditions, and the newly found opportunities.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

András and Eszter

![]()

Whatever is, was and remains

![]()

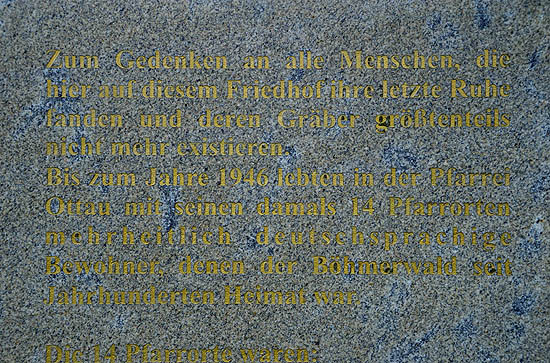

Passing away, survival, recreation – these were the main topics in my mind along the way, and they structure also my memories…

The merry cemetery in Szaplonca/Sapânța, whose epitaphs so unusually recall the simple or very unique life and death of the ones resting there… Then, the abandoned Hasidic cemeteries, sunken in the past, evoking the opposite feeling with their impersonality sheding an infinite calmness…

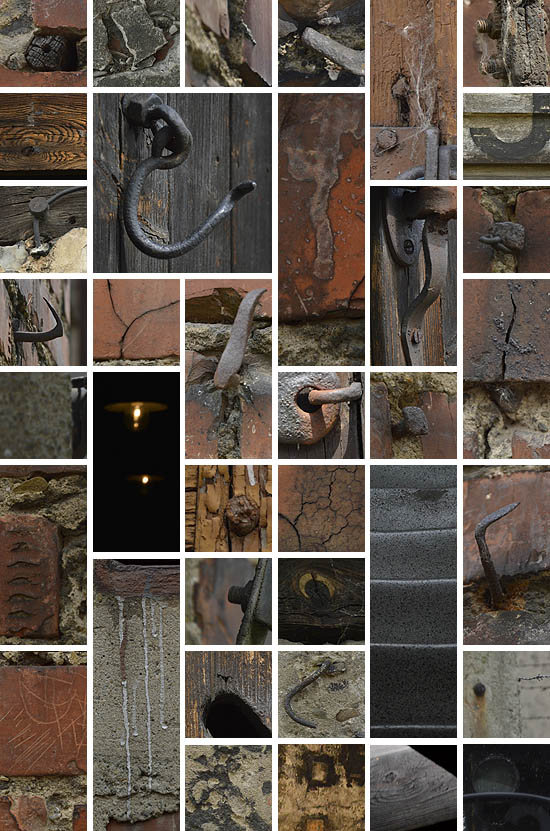

The incredibly thick, long, dark, cracked beams…

The winding up of the creation, as the angels carry it out on the wall of the Orthodox churches…

The newly built monasteries, which might be re-creators, and certainly determinants of the existence of the neighborhood...

And as it is surrounded by the fifty shades of green, the landscape, with the illustrations of the past in it, like the shingle-roofed, sometimes dilapidated houses, the wood-fired little steam engine, the carriage crossing the ford, accompanied by a little dog… well, the mountains, the valleys, the meadow, the flowers, the streams, the rivers, the waterfalls. All whatever is, was and remains.

![]()

Ágnes

![]()

First and finally

![]() If I could completely freely write,

If I could completely freely write, I would first write about the landscape. Not only that there were mountains, valleys and forests, but I would try to describe that all this was together, at the same time; a gentle and strong and composite landscape, you could watch it for hours, as if you were reading it. And cheerful and spacious at the same time. Second, I would write, and it would be evoked by this compositeness and spaciousness, that this is like friendship, they were somehow linked in me.

I did not open the book I took with myself, because everything I saw and in which I participated was much more exciting. You could read the wide variety of cultures and ways of life, past and present, which we were traveling through. Or perhaps only browse it. I do not understand it so much to become a reader of it.

![]() The Bible of the poor,

The Bible of the poor, this is what I recalled at the walls of the painted churches and monasteries, at the carved graveposts. Everything was filled with signs, so that those who understand the language of these pictures, could recognize the stories and read out their essence. Here perhaps past tense would be necessary. The ones who understood the language of these pictures. Where are they? It was good that we could quite freely ask. I sometimes asked as a child. I do not forget how well Ferkó asked.

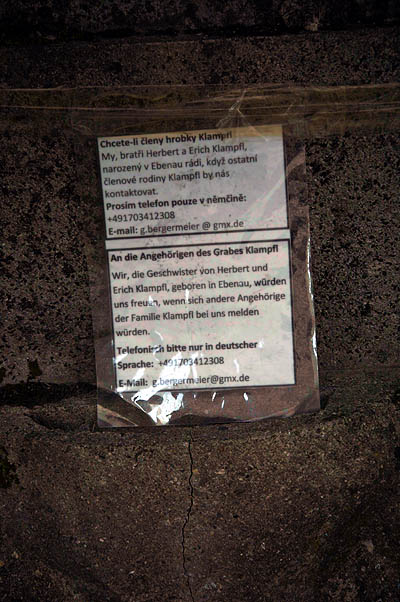

I read something strange on the window of the last synagogue of Máramarossziget/Sighetu Marmației, but then, as I have also forgotten the few Romanian I once knew,

![]()

I thought I was surely wrong, the text on the sheet of paper is not what I guess. At home it turned out that reality was far more miserable. I got to know the content of that inscription from the

essay of Zsolt Láng, illustrated by the photos of Noémi Kiss (Zsolt Láng is a great Transylvanian prose writer, Noémi Kiss is an excellent writer in Budapest, a fellow traveler of río Wang)

“Dear compatriots! We ask you with respect and friendship to respect our synagogue just as you respect your churches. We have the same God, who is benevolent, but also ruthless with those who damage His sacred dwelling. The Jews did nothing bad to you. It is possible that when much more Jews lived here, you did not live worse than now. It would be uncomfortable if our town were considered a dwelling place of anti-Semites and drunkards. Thank you for your understanding!”![]()

I do not forget the face of the young man who opened to us the synagogue, it had something apologetic.

Elephant– this place was a real surprise. True, a surprise which you could expect in any valley and at any corner of any village in that region. If they did not preserve the mountain railway, no tourists would go to Felsővisó/Vișeu de Sus. If they did not sell good beer and excellent coffee in the Elephant, nobody entered the museum. If there were no museum, then the memory of the Jews of Wischau would not survive. The last owner of the sawmill, Sándor Elefánt, in whose house the exhibit takes place,

seems to have been a great person. “The other members of the community also exert valuable economic activity.

![]()

Among them emerges Sándor Elefánt, member of the county’s committee, whose sawmill gives bread to 150 people. The mills of Mózes Steinmetz Mózes and Mechel Kratz employ 80 people. 60 people work in the sawmill of Lázár Fruchter Jr., and 70 in the mill of Wolf Léb. The Jewish community has an annual budget of about 600 thousand lei. Its registry area includes the villages of Középvisó, Alsóvisó, Leordina, Petrova, Bisztra, Majszin, Szacsal, Jend, Szelistye, Dragomérfalva, Konyha and Kisbocskó. Its population is about 5000, the number of families 900. It is interesting, that the community imposes no obligatory taxes on its members, thus the costs of its administration are covered from the voluntary donations of its members. The members of the community took part in a great number in WWI, 16 among them died a hero’s death. The present leadership of the community includes Wolf Léb, Sándor Elefánt and Fischel Fogel as presidents, treasurer Ferdinánd Silberherc, auditors Sámuel Teszlerand Eizik Illovits, Talmud Torah supervisor Littman

![]()

Brettler, community counselor Sámuel Fliegelmann, economic supervisor Iczik Mojse Kora, charity supervisor Adolf Kann, superiors Mózes Steinmetz, Mózes Mármor, Hers Fruchter, Lázár Fischler, Hers Krátz Mechel, Ferenc Grünbaum, Ábrahám Weinberger, Salamon Meilich, Emánuel Niszel and Lázár Stein, chief rabbi Mendel Háger, assistant rabbi Dávid Weisz, cantors Bernát Horovitz and Hers Pollák, and recorder Izidor Fogel.” This is how it was in 1929. Tamás, what is the origin of the Jewish family name Elefánt? What is its history?

*Finally I would again write about the landscape, in the most spacious way possible.

It was quite beautiful.Teri

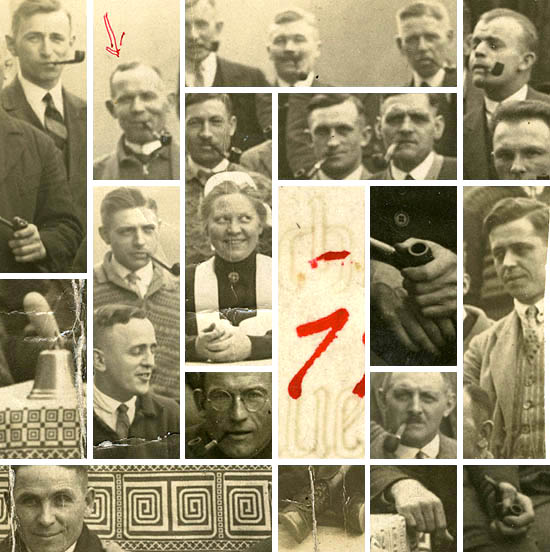

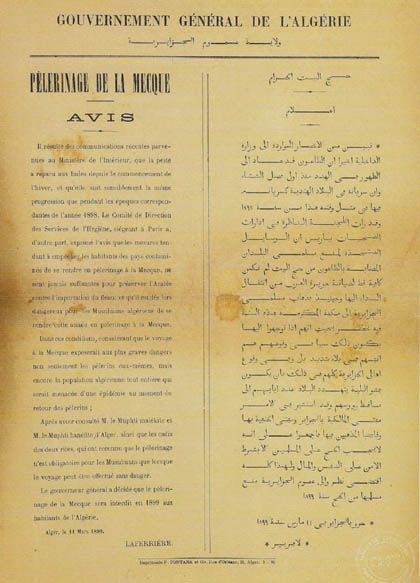

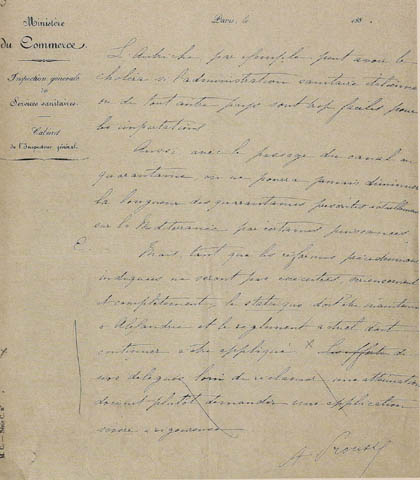

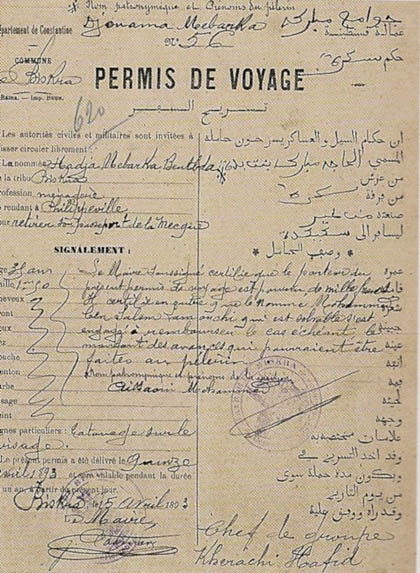

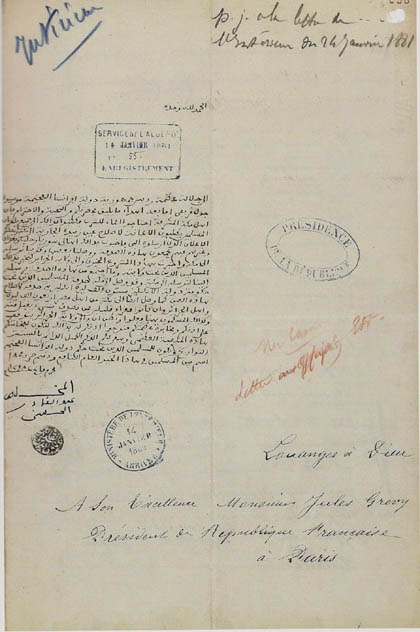

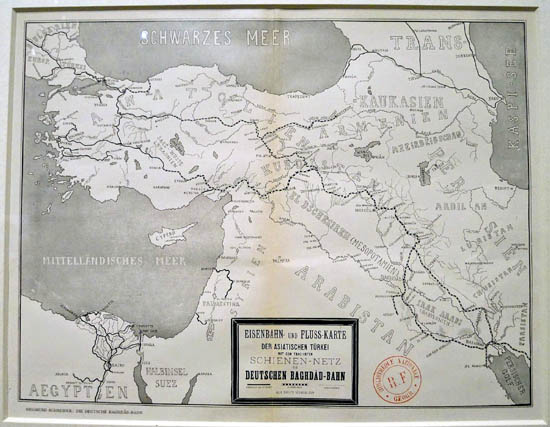

Today I went to the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin to see the First World War exhibition, heralded with great fanfare. It is vain to waste many words on the exhibition, when a single one describes it: boring. In the basement, in one large room, a turbulent installation tries to present the entire history of WWI. The attempt is a complete failure. Anyone who does not already know the progress of the war in detail will not be able to assemble into one coherent picture the objects exhibited in separate stalls, which are labeled with the names of various theatres of operation, and presented in an “ach, wie schrecklich, der Krieg!” way to maximize the emotional effect. And anyone who knows it will clearly see the random and commonplace character of the selections. I would have not even written about it, if, just before the exit, in the stall dedicated to the post-war developments, I had not caught sight of one last exhibition object.

Today I went to the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin to see the First World War exhibition, heralded with great fanfare. It is vain to waste many words on the exhibition, when a single one describes it: boring. In the basement, in one large room, a turbulent installation tries to present the entire history of WWI. The attempt is a complete failure. Anyone who does not already know the progress of the war in detail will not be able to assemble into one coherent picture the objects exhibited in separate stalls, which are labeled with the names of various theatres of operation, and presented in an “ach, wie schrecklich, der Krieg!” way to maximize the emotional effect. And anyone who knows it will clearly see the random and commonplace character of the selections. I would have not even written about it, if, just before the exit, in the stall dedicated to the post-war developments, I had not caught sight of one last exhibition object.

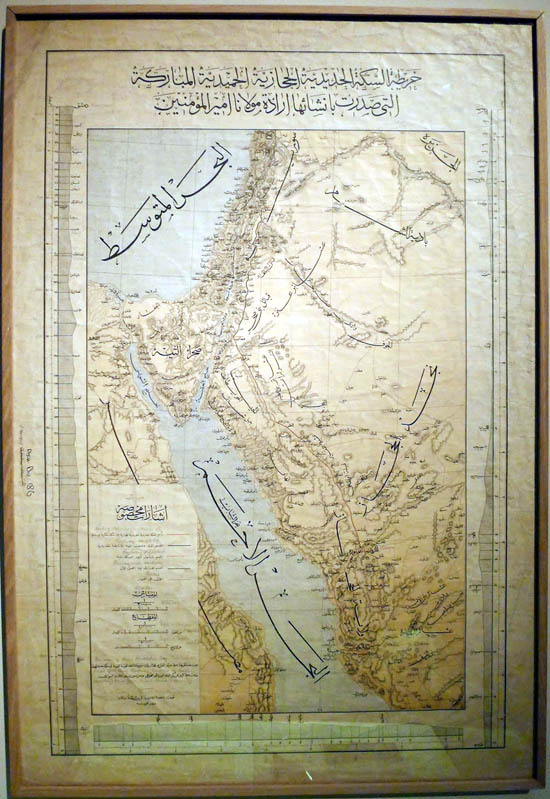

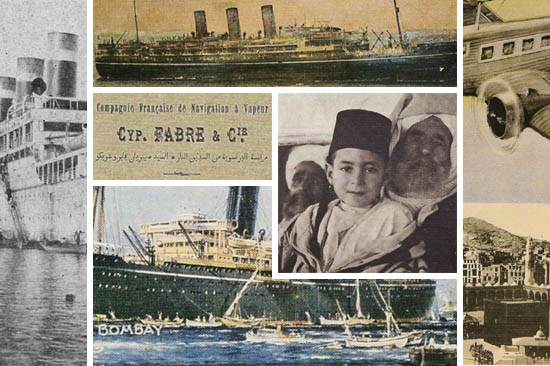

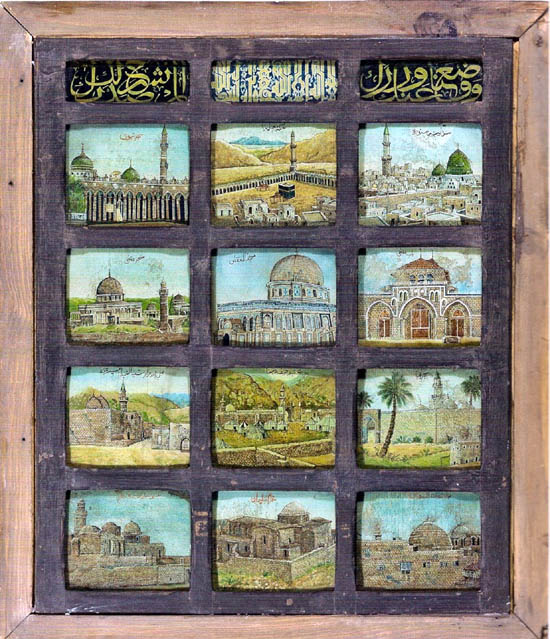

— Et pourquoi n’iriez-vous pas à La Mecque ?

— Et pourquoi n’iriez-vous pas à La Mecque ?

– And why don’t you travel to Mecca?

– And why don’t you travel to Mecca?

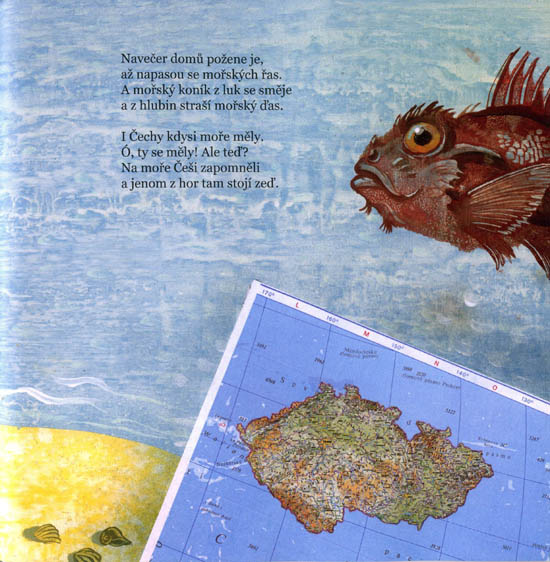

Pequeños guijarros sobre las tumbas.

Pequeños guijarros sobre las tumbas.

Abajo: Columna para imágenes sagradas —le faltan las imágenes—, característica de la región de los Alpes. Superviviente de la segunda mitad del siglo XV.

Abajo: Columna para imágenes sagradas —le faltan las imágenes—, característica de la región de los Alpes. Superviviente de la segunda mitad del siglo XV.